THINKING OUTSIDE THE TOOLBOX

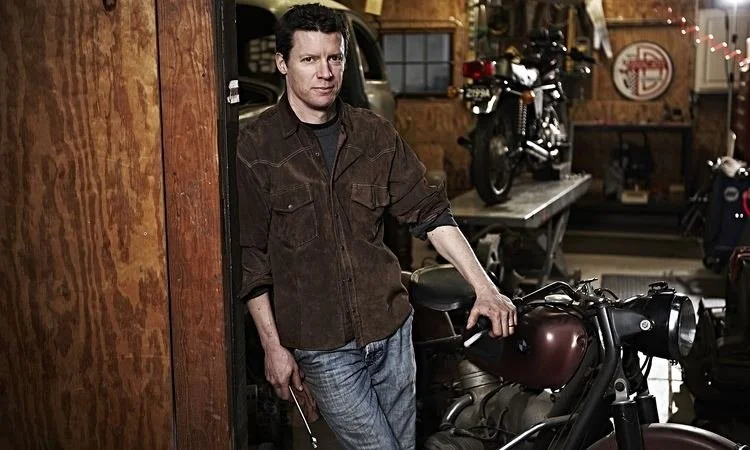

RICHMOND, VA, 2006 — Bikers bringing a busted Harley into Shockoe Moto don’t care that its head mechanic has a Ph.D. in political philosophy. They just want someone to fix their bike. But Matthew B. Crawford has a lot to say about tools, so-called “manual labor,” and where an “upskilled” America went wrong. The problem is not in our tools but in ourselves.

“A decline in tool use would seem to betoken a shift in our relationship to our own stuff: more passive and more dependent. . . What ordinary people once made, they buy; and what they once fixed for themselves, they replace entirely or hire an expert to repair, whose expert fix often involves replacing an entire system because some minute component has failed.”

Balancing unlikely jobs — mechanic and philosopher — Crawford may be the renaissance man America needs. Since 2001, when he left a DC think tank to open a motorcycle shop, he has become a guru of gearheads and the kind of “hands on” yeoman that Thomas Jefferson would have loved.

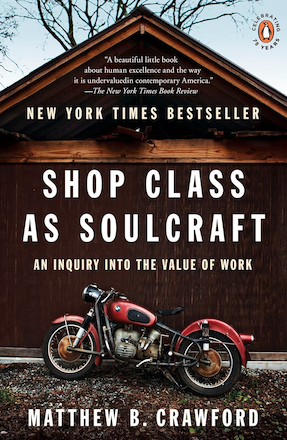

“One of the most influential thinkers of our times” (Times of London) is a label not worn lightly by a guy as comfortable riding as writing. But Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft speaks to an America wondering why more and more screens have not made us happy. Happiness, Crawford expained, is in our own hands.

“The current educational regime is based on a certain view about what kind of knowledge is important: ‘knowing that,’ as opposed to ‘knowing how.’”

Crawford’s path to “influential thinker” was delightfully wayward. The son of a Berkeley physicist, he grew up in a commune and did not attend school until age sixteen. By then he was learning to be an electrician and had discovered motorcycles.

A physics degree failed to get him a job, so Crawford taught Latin and read and read. One book he read, The Closing of the American Mind, drew him to the University of Chicago to study under its author, Allan Bloom. “We didn’t hit it off,” Crafword recalled, but he stayed to get his doctorate in political philosophy.

Academic jobs were few so Crawford became executive director of the George C. Marshall Institute. It took him just months to burn out. Though he’d rejected “the liberal pieties of Berkeley,” Crawford blanched at “coming up with the best arguments money could buy. This wasn’t work befitting a free man, and the tie I wore started to feel like the mark of a slave.”

While studyhing Aristotle, Kant, and company, Crawford was still hooked on the “drug” of motorcycles. And when stumped on repairing his Honda, he met a mechanic who bridged the gap between the classroom and the shop floor. Fred Cousins “gave me a succinct dissertation on the peculiar metallurgy of these Honda starter-motor bushings of the mid-70s. Here was a scholar.”

Once he immersed himself in the complexities of engines, brakes, and fuel lines, Crawford “quickly realized there was more thinking going on in the bike shop than in my previous job at the think tank.“

At this point, if you are tempted to play the class card, blue vs. white collar, Crawford knows just where that card leads — back to shop class.

Remember shop class? The power tools. The workbenches. The smell of sawdust and the sense that, even if your “toolbox” had barely a square angle, you made it. Yourself.

Alas, all that is history, because as Crawford notes, “lot of schools shut down their shop class programs in the 1990s, when there was a big push for computer literacy. To pay for the new computers.”

While running Shockoe Moto, Crawford wrote a book that no one thought a likely best-seller. Shop Class as Soulcraft cites Socrates, Heidigger, and Hannah Arendt, but it also quotes several mechanics and “a certain shop teacher whose name I have lost.”

If we now seem perpetually unsatisified, blame it on the digital, Crawford explained. “I think there’s also a very common human thing, which is to take a tool in hand and see a direct effect in the world. I think that answers to something deep about our nature.”

Published in 2009, Shop Class touched a nerve. The New York Times called it “a beautiful little book about human excellence and the way it is undervalued in contemporary America.” The New Yorker saw it as “a declaration of gearhead pride in an ever more gearless world.”

Suddenly Crawford had to leave the shop floor to speak at conferences, on TV, at bookstores. He was offered a position as fellow at the University of Virginia’s Institute for Cultural Studies. He signed on, but kept his shop. And his bike.

Today, shop classes remain rare. And we continue to downplay “blue collar” work and laud college as the answer for everyone. Crawford disputes the dichotomy.

“My sense is that some kids are getting hustled off to college when they’d rather be learning to build things or fix things, and that includes kids who are very smart,”

Since Shop Class, Crawford has written numerous articles and books. In Why We Drive, he laments the “electronic bullshit” that pervades today's cars and destroys the fun of driving. In The World Beyond Your Head, he thinks about thinking, or the lack thereof.

“The media have become masters at packaging stimuli in ways that our brains find irresistible, just as food engineers have become expert in creating ‘hyperpalatable’’ foods by manipulating levels of sugar, fat, and salt. Distractibility might be regarded as the mental equivalent of obesity.”

Though couched in intellectual arguments and tautologies, Crawford’s soulcraft is basic and accessible. Turn away from screens. Fix something. Build something. Use tools, including your own mind. And never assume a mechanic is any less a thinker than you’ve been told.

“You might be surprised how many intellectuals there are out there who haven’t done a lot of higher education.”