SEQUOYAH AND THE "TALKING LEAVES"

TUSKEGEE, TN, 1821 — The little girl doesn’t seem like a witch. Nor does her father. But what is this sorcery? Passing words and thoughts from one to the other without speaking? The elders are concerned.

On into the 1800s, some 500 native languages were spoken across America. The most beautiful names on our maps are all native. Missouri. Shenandoah. Biloxi. Susquehanna. But all 500 languages were oral, with no means of writing or reading their ancient wisdom. Until one man, part-time silversmith and full-time genius, single-handedly moved his nation from its pre-literate state to full literacy.

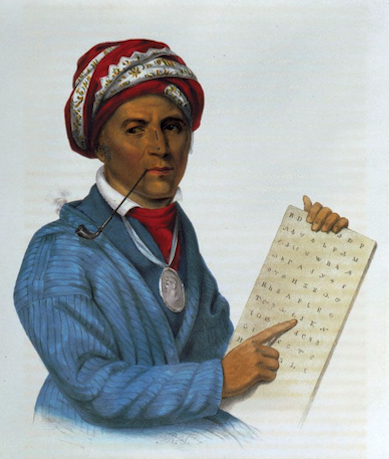

These days, Sequoyah is a giant tree, a national park, an SUV. But among the Cherokee, Sequoyah is the ancestor who wrote their future.

“The greatest weapon, or shield, that we were ever given are two things,” said Cherokee Chief Chuck Hoskin, Jr. “The language given to us by our Creator and the written language given to us by one man, the genius Sequoyah. I think in a very real way, had Sequoyah not invented this syllabary, we wouldn’t be here today.”

Born on the edge of survival, Sequoyah was known throughout his small village as a creator. Despite a chronic limp, he designed farm tools, made jewelry, and was always leaving his chores to tinker with some new dream. His mother, Wu-tah, was patient, but Sequoyah never went to school, never learned English. He might have suffered the fate of all Cherokee if not for the “talking leaves.”

By 1808, working as a silversmith, Sequoyah was meeting European merchants passing through Tennessee. He marveled at the letters they received from home. These scraps of paper, scratched with baffling marks, made men laugh or cry. Sequoyah called them “talking leaves.” Why couldn’t the Cherokee speak on paper?

Like the creators of the first written languages, Sequoyah began with pictographs. Each word, each idea should have its own symbol. But this proved impractical. No one could memorize so many signs. After other false starts, he settled on a syllabary — a different shape for each spoken syllable — eight-six in all.

A handy Bible provided Latin letters — R, K, M, etc. No one has ever explained how Sequoyah found shapes that look eerily like Greek, Cyrillic, and Slavic alphabets. But working, even obsessing over his syllabary got Sequoyah in trouble. Neighbors thought he’d lost his mind. His wife agreed. And in 1821, when he taught his finished syllabary to his daughter, the two were tried for witchcraft.

As elders watch, Sequoyah sends Ayoka out of the room. He asks an elder to say a few words, then he scribbles marks on parchment. When he calls his daughter back, he says nothing, just shows her the scribbles. And she says the words! Witchcraft? Trickery? When they perform the feat again, elders are convinced. Can he teach them this magic?

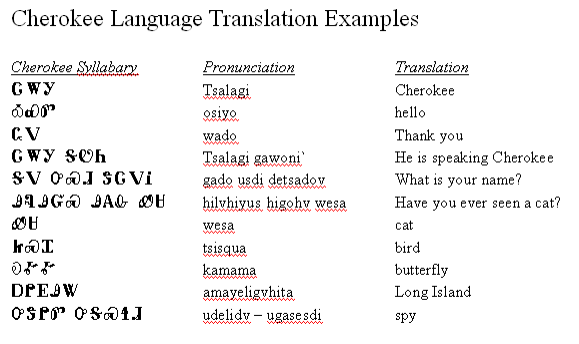

ᏣᎳᎩ, aka Cherokee, is not as hard as it looks. The 86 symbols are read left to right, each in a row that links a different consonant with the same vowel sound. Using the English alphabet, the Cherokee word for water is ama. But in written Cherokee, the word has two characters, not three. The D is pronounced “ah,” and the Ꮉ says “ma.”

No silent letters. No weird English spellings. Just common sense and sound. Sequoyah took his syllabary on the road, teaching it to Cherokee from Tennessee to Arkansas. To reach those who had yet to move west, he transcribed a chief’s speech, sealed it in an envelope, then went to North Carolina and read it aloud.

Word spread, especially when the Bible and the laws of the Cherokee nation were transcribed. Within a few years, 90 percent of Cherokee were literate, well more than the number for local white settlers. Then in 1828 came the Cherokee Phoenix.

America’s first bilingual newspaper, the Phoenix printed news of the Cherokee nation in both English and Sequoyah’s syllabary. The first issue had an article praising Sequoyah and an editorial criticizing whites as greedy for land. But then as now, other news was ominous.

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act. First the Choctaw, then the Seminole and Chickasaw, and finally the Cherokee were uprooted from ancestral lands and marched west. In any language, call it “ethnic cleansing.” Some 4,000 Cherokee died on the Trail of Tears. When they reached Oklahoma, they found Sequoyah waiting.

While representing the Cherokee during negotiations in Washington, DC, Sequoyah met other natives. Conversations inspired him to create a universal syllabary for several native languages. He went as far as Arizona and New Mexico, learning languages and struggling with syllables.

After settling in Oklahoma, Sequoyah helped re-unite the divided Cherokee nation. But on a journey into Mexico, he died of respiratory failure. His syllabary, though it inspired similar systems in 21 other oral languages, almost died with him.

Rounded up on reservations, natives were sent to schools where their languages were banned. The Cherokee Phoenix went out of print. The Cherokee language withered. But in the 1970s, when native cultures began a revival, Sequoyah’s syllables, like some forgotten Greek texts, could still speak.

In 1975, the Cherokee Phoenix earned its name by rising from its own ashes. That same year, a tribal linguist published the first Cherokee-English dictionary. A decade later, Sequoyah’s syllabary was encoded into computer fonts still found on MAC and Windows.

Some 2,000 people now speak Cherokee and thousands more are learning to read and write the language. Cherokee is taught at universities in Oklahoma and North Carolina. And Sequoyah is remembered as the genius whose syllables helped a language and a nation endure.

Durban Feeling, Cherokee linguist, paid tribute. “Every day,” he tells students, “every day just keep speaking Cherokee. If you do that, it will all be okay.”