THE WOMAN WHO SAID 'NO!' TO NIXON

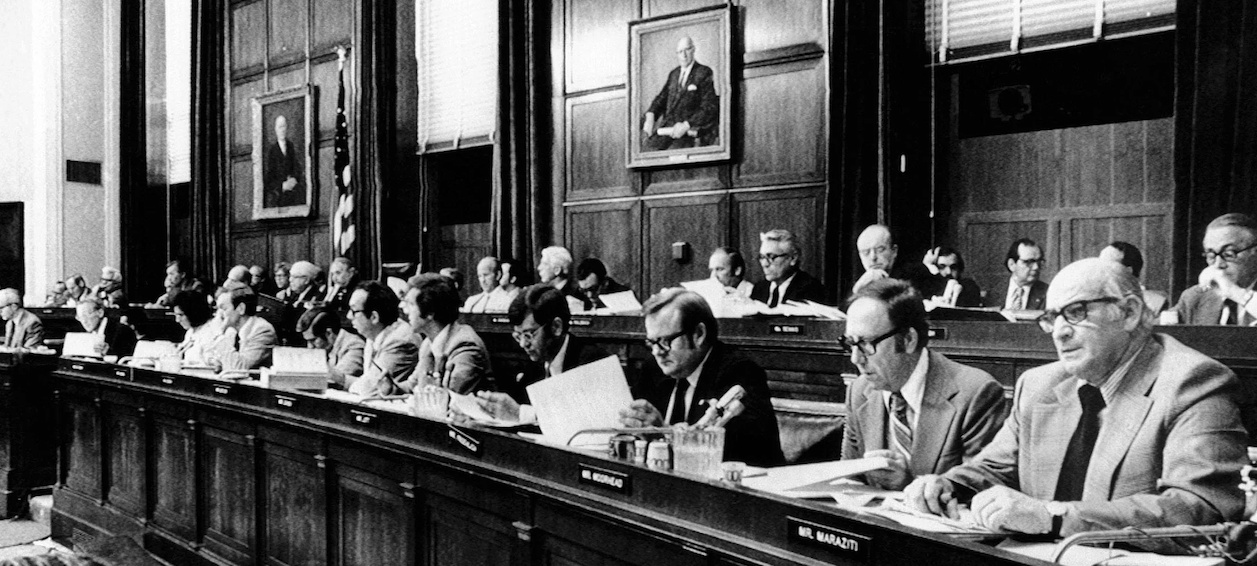

WASHINGTON, D.C. JULY 25, 1974 — Three-dozen suits sit in neat rows on this solemn occasion, the first presidential impeachment in a century. As TV cameras pan the House Judiciary Committee, they catch a lone woman in a red dress.

Skin color also stands out, yet her colors are soon silenced by the voice of democracy. Sounding part preacher, part teacher, and entirely American, Barbara Jordan begins:

“Earlier today, we heard the beginning of the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States: ‘We, the people.’ It's a very eloquent beginning, but when that document was completed on the seventeenth of September in 1787, I was not included in that ‘We, the people. . . ’”

Barbara Jordan was a Congressional comet. Following her stirring Watergate speech, she commanded nationwide attention for just five years. Then, choosing not to run again, she spent the rest of her life teaching at the University of Texas.

When she died in 1996, Texas governor Ann Richards gave the eulogy: “In a world that sways on the winds of trends and polls and prognostications, she was a constant, and she was as true as the North Star. Barbara Jordan was an American original and a national treasure.”

Like many treasures, she was hard to find at first. Daughter of a Baptist preacher, Jordan grew up in Houston’s Fifth Ward, known to The Texas Observer as a “crummy Southern ghetto.” Yet Jordan stood out from the start. Tall and gangly with a resonant baritone, she wanted to be a lawyer, or perhaps a politician like her great-grandfather, one of the last black Texas politicians before Jim Crow.

Barred from the all-white University of Texas, Jordan studied at Texas Southern. There she captained a debate team that defeated Ivy League schools. Studying law at Boston University, she was the only woman in her class. Back in Houston, she worked for JFK and befriended his vice-president, a fellow Texan.

With LBJ’s encouragement, Jordan ran twice for state rep, and lost. Then in 1966, she was elected to the state senate, the first black woman. . . A legion of “first” followed, culminating in “first Southern black Congresswoman” in 1972. Her legal expertise, and LBJ’s pull, landed her on the House Judiciary Committee. In any other era, they would have worked behind closed doors, but this Judiciary Committee was on a collision course with President Nixon.

Jordan dreaded impeachment. ”You’re talking about the presidency,” she thought. “You’re not going to impeach the President!” But as Watergate ground on, Jordan did her homework, and by that fateful summer of ‘74, she saw no alternative.

She warned her colleagues against “speech making.” This had to be about Nixon, not their “fifteen minutes on television.” But in a parade that lasted two days, every member of the committee spoke. Finally Jordan saw that, “by the next evening they would get around to me.”

“I know you’re going to let Nixon have it,” friends said, but Jordan saw her task governed by “reason, not passion.” “I was not going to vote to impeach Richard Nixon just because I didn’t like him.”

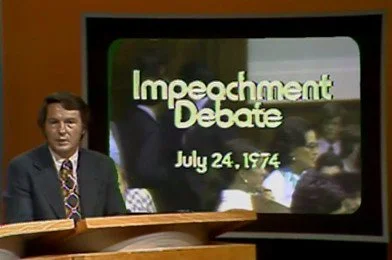

On July 24, when the committee recessed for dinner, Jordan sat at her desk with “disjointed notes that I’d written from all of my reading on impeachment. But I didn’t have a statement.” Every speech so far had cited We, the people. “It occurred to me that not one of them had mentioned that back then the Preamble was not talking about all the people. So I said: ‘Well, I’ll just start with that.’”

8:30 p.m. Prime time on a hot summer night. Barbara Jordan continues.

“. . . I was not included in that ‘We, the people.’ I felt somehow for many years that George Washington and Alexander Hamilton just left me out by mistake. But through the process of amendment, interpretation, and court decision, I have finally been included in ‘We, the people.’"

She then lays out the case against the president and for the Constitution. “My faith in the Constitution is whole; it is complete; it is total. And I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” Next, she defines “impeachment,” quoting Hamilton, Madison, Woodrow Wilson. . . She lays out Nixon’s “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Watch:

An hour later, Jordan leaves the Rayburn Office Building to find a crowd around her car. Cheers. Shouts of “Right on!” Telegrams and letters pour in.

Nixon’s supporters are outraged. “You should beg God to forgive you for your part in attempting to destroy a great man.” But hate mail is overwhelmed by thanks and praise.

— “A literary masterpiece. . .”

— “God Bless you, Honey! You were wonderful!”

— “Do not weary of your task. We need your honest, forceful voice.”

Jordan later electrified the 1976 Democratic Convention as keynote speaker. The following year, she rallied women at their National Conference in Houston. Then in 1979, suffering from multiple sclerosis, she left Congress. She returned to the national stage only for another keynote convention speech in 1992. In a wheelchair. Four years later, she died of leukemia. She was 60.

Dozens of schools, highways, and buildings throughout Texas are named for Barbara Jordan. She earned honorary doctorates from Harvard, Yale, and other universities plus the Presidential Medal of Freedom. But it will always be her words, and that voice, which resound whenever democracy is endangered.

“There is no executive order; there is no law that can require the American people to form a national community. This we must do as individuals and if we do it as individuals, there is no President of the United States who can veto that decision.”