A GENIUS AND HIS MAGIC CAMERAS

A photo captures more than light. It also captures time. “Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it,” Susan Sontag wrote, “all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.”

In our time, when more photos are snapped each day than were taken in the entire 19th century, we take photography’s time machine for granted. But for more than a century, photography was a game of “hurry up and wait.” Snap a photo in a split second, take the film to the drug store. If you’re lucky, maybe a week later. . . Then one genius and his cameras changed that.

Edwin Land never tired of telling the story. How one afternoon he took a photo of his three-year-old daughter. She asked to see herself — now! But they had to wait. Why? Why? Why indeed, Land thought. He went for a walk and “within an hour, the camera, the film and the physical chemistry became so clear to me."

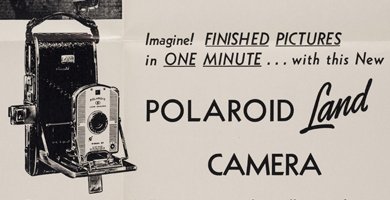

The day after Thanksgiving in 1948, the Land Camera went on sale at Jordan Marsh in Boston. At $89.95 ($1,100 today) Land thought sales would be modest but by closing time, every camera in stock had sold. Seems we can’t wait to freeze the moment, to capture time.

Long before Apple coined the phrase, Edwin Land learned to “think different.” At six, he blew all the fuses in his family’s Connecticut home. Just “Din,” as his sister called him, tinkering again. All that tinkering got Land into Harvard but long before Steve Jobs and Bill Gates modeled the dropout entrepreneur, Land left Harvard after one year. Fascinated by light, he moved to Manhattan where he began tinkering with polarization.

Science knew that light can be filtered to align its rays. Polarized filters create sun glasses and also sculpt the screen you’re reading now. But filters were expensive and bulky until Land invented thin sheets of crystals that did the job. In 1932, this invention kicked off the Polaroid Corporation. At Polaroid, Land tinkered with filters for a dozen years before his daughter asked the question that steered him into photography.

The first Land camera, though it seemed a miracle, was awkward. Using chemicals built into the film, it developed images inside the camera. Wait 60 seconds, open the back, and there was your moment in time. But Land was just getting started.

Polaroids, all black-and-white, soon developed outside the camera. Yank out the photo, which spread the chemicals, wait 60 seconds, peel back, and. . . Then in 1963 came instant color photos. By the late 1960s, half of all American homes owned a Polaroid. We hadn’t seen anything yet.

Because along with “thinking different,” Land thought relentlessly. “Knowing him was a unique experience,” a Polaroid colleague said. “He was a true visionary, a brilliant, driven man who did not spare himself and who enjoyed working with equally driven people.”

From the moment his mother caught him taking apart the family phonograph, the young Land vowed that “nothing or nobody could stop me from carrying through the execution of an experiment.” As a young inventor in Manhattan, he often snuck into the lab at Columbia to use the equipment. He once wore the same clothes for three weeks while he worked and worked. “Anything worth doing,” he joked, “is worth doing to excess.”

But Land was more than driven; he was conscientious. Along with instant photography, Polaroid pioneered fair hiring, Land insisting that his company employ large numbers of women and people of color. Land consulted with presidents from Eisenhower to Nixon but during Watergate, he resigned in protest.

Then in October 1972, Land released his most amazing camera yet. Like an Apple product rollout (which many say were based on Land) he debuted it himself. Onstage at Polaroid’s annual meeting, he pulled a flat box from one pocket, tapped to expand it, and snapped five photos. Each photo came shooting out of the camera. As awed employees watched, each developed itself, the images darkening in front of their eyes.

The SX-70 cost $150, equivalent of $1,000 today. But nearly a million were sold. Photographers from Ansel Adams to Andy Warhol loved the SX-70. LIFE put Land on its cover headlined: A GENIUS AND HIS MAGIC CAMERA.

Alas, not even a magic camera can truly freeze time. It marches on, taking technology with it. In the 1980s, a future named Steve Jobs met the past named Edwin Land. “It was like visiting a shrine,” said Jobs, who had long idolized Land. “He saw the intersection of art and science and business and built an organization to reflect that."

When Land died in 1991, with 535 patents to his name, Polaroids were still the only instant cameras. Within a decade, anyone could see instant photos on any digital camera. And once iPhones put cameras in every pocket, Edwin Land and his magic seemed relics of another time.

You can still buy Polaroids. Artists love them, as do the nostalgics who revived vinyl records. But time these days is frozen into digits, not chemicals. Land would have understood. Though he was the soul of a major corporation, he cherished the lone tinkerer with an idea and a dream.

“If you are able to state a problem,” he often said, “then the problem can be solved." And optimism, he added, "is a moral duty.“