A MIND FOR THE MASSES

Mathematics holds a curious place in our minds. Masters of math see its equations as the language of the universe. The rest of us see an equation and back away slowly. And then there is Martin Gardner.

Call him a polymath, then consult Webster’s: polymath, n., a person of encyclopedic learning.

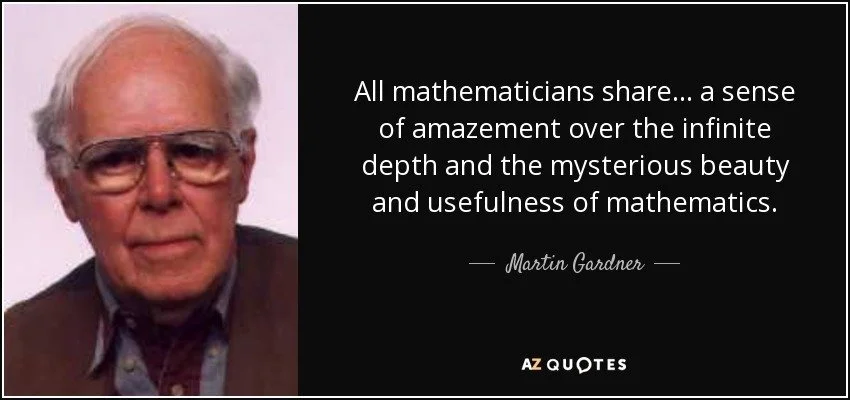

Gardner never took a college math course yet his Scientific American columns earned the respect of noted mathematicians. With a mind at play, he practiced magic, loved card tricks, and relished puzzles. Yet he scoffed at anyone who claimed definitive answers to anything.

“There may be advanced life-forms in Andromeda who know the answers,” he wrote at the end of his long life. “I sure don’t. And neither do you.”

Along with voluminous writings about philosophy, psychology, even economics, Gardner relished debunking pseudoscience from astrology to scientology. Yet he believed in God, or some "Wholly Other transcendent intelligence,” and in an afterlife.

Above all, this polymath believed in “recreational math,” i.e. math for the hell of it. And while most math wizards speak only to each other, Gardner’s 100+ books brought his childlike fascination with math to the masses.

Quoth Noam Chomsky (making his Attic debut): “Martin Gardner's contribution to contemporary intellectual culture is unique – in its range, its insight, and understanding of hard questions that matter." A mathematician said it more simply. Gardner was “the most learned man I ever met.”

The son of a petroleum engineer and a Montessori teacher, Gardner grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma during the 1920s. His father gave him math puzzles; his mother taught him to read using The Wizard of Oz books.

In high school, Gardner struggled into calculus but at the University of Chicago he turned to philosophy. He served on a destroyer in World War II, then dropped out of grad school and moved to Manhattan to become a writer. His first job — editing a children’s magazine.

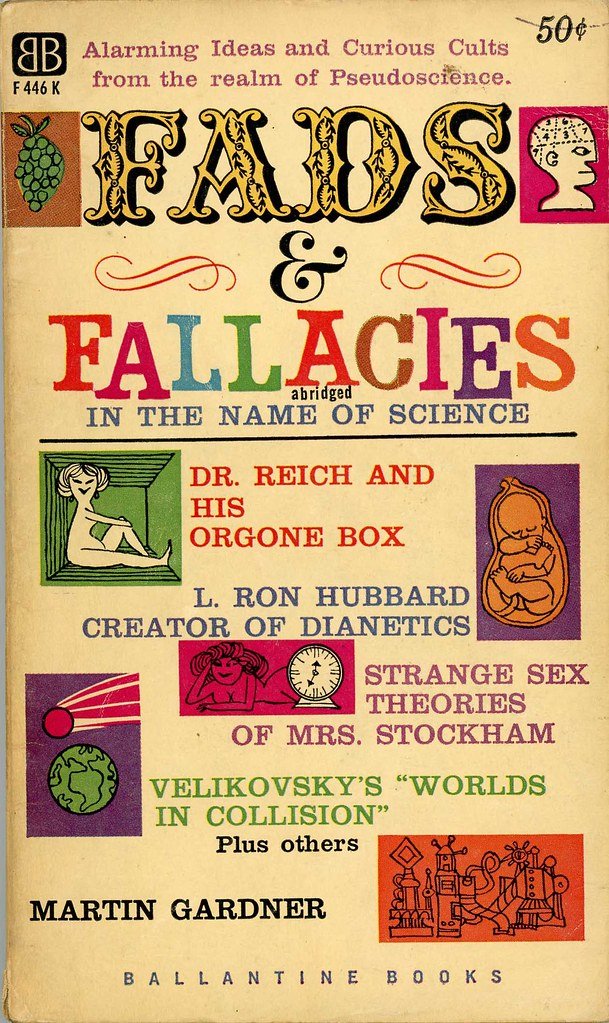

During eight years at Humpty Dumpty, Gardner continued to stretch his mind. He wrote freelance articles on origami, geometric puzzles, and the rise of silly science. He turned the latter topic into his first book.

In 1957, Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science jumpstarted the modern skeptical movement.

READ “MARTIN GARDNER’S SIX WAYS TO SPOT A ‘CRANK’

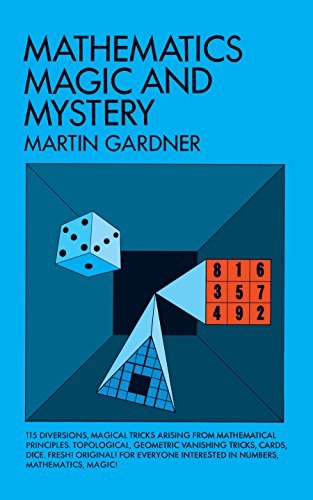

That same year, Gardner’s writing about math opened a door to a wider audience when Scientific American hired Gardner to do a monthly math column.

On into the 1980s, “Mathematical Games” introduced dabblers like himself to such arcane topics as fractals, möbius strips, Zeno’s paradox, Fibonacci numbers, and the mystical art of M.C. Escher.

Gardner’s math was more playful than pedantic. It helped, he said, to have struggled with math. "I go up to calculus, and beyond that I don't understand any of the papers that are being written. . . If you are writing popularly about math, I think it's good not to know too much math.“

Yet mathematicians appreciated Gardner at play in their field. Checking and re-checking his math, he kept in constant touch with what one called “Gardner’s mathematical grapevine.” His 300+ columns eventually filled dozens of books and countless minds.

One future Google engineer never forgot: “A case can be made, in purely practical terms, for Martin Gardner as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. His popularizations of science and mathematical games in Scientific American, over the 25 years he wrote for them, might have helped create more young mathematicians and computer scientists than any other single factor prior to the advent of the personal computer.”

Gardner’s skepticism also had wings. In 1976, he co-founded the Committee on Skeptical Inquiry and began writing for its monthly magazine Skeptical Inquirer. Though his first book had been “a study in human gullibility,” mostly in the 19th century, Gardner was appalled at the persistence of sheer bunk in our times.

“My own opinion is that the gullibility of the public today makes citizens of the nineteenth century look like hard-nosed skeptics.”

Playing, writing, helping raise two sons, Gardner also found time to indulge his childhood love affair with lit. He co-founded the International Wizard of Oz Society and put Lewis Carroll under his microscope, emerging with The Annotated Alice, which has sold a million copies. Why add footnotes to a “children’s book?”

“In the case of Alice, we are dealing with a very curious, complicated kind of nonsense, written for British readers of another century, and we need to know a great many things that are not part of the text if we wish to capture its full wit and flavor.”

Eccentric and “interested in everything,” Gardner played the musical saw and used an abacus to balance his checkbook. He never wrote on a computer, yet he continued to write into his nineties, and his range remained astonishing. To wit: “Klingon and Other Artificial Languages,” “Puzzles in Ulysses,” “Nothing,” “Everything.”

At 96, Gardner took Oprah Winfrey to task for buying into the bunk about vaccines and autism. A month later, he died in his apartment in Norman, Oklahoma. Gardner’s death, however, did not cancel out his equations.

Each week, Gathering 4 Gardner holds Zoom meetings out of its base in Atlanta. And whatever afterlife Martin Gardner may have entered, he created his own in his enduring books, columns, and infectious sense of wonder.

Don’t believe nonsense, he taught us. Steer clear of the pedants, the preachers, the zealots. Be “a Mysterian” with more awe than answers.

“We humans are incredibly tiny things in a universe that is huge and full of wonders.”