"MY FARAWAY ONE"

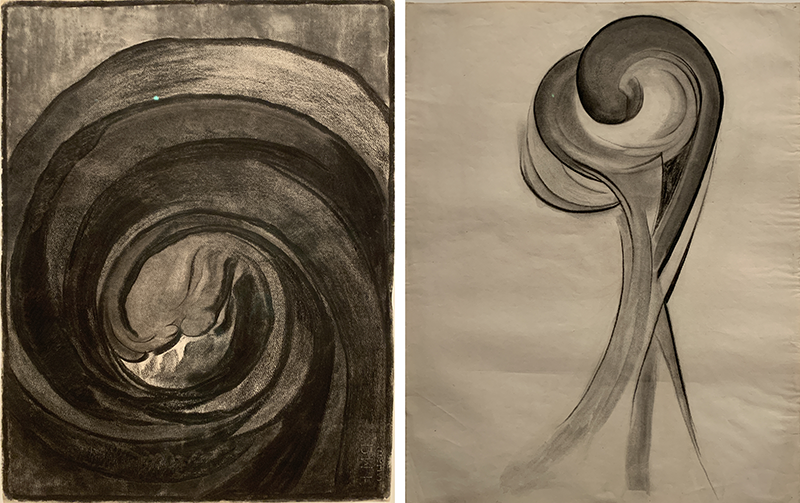

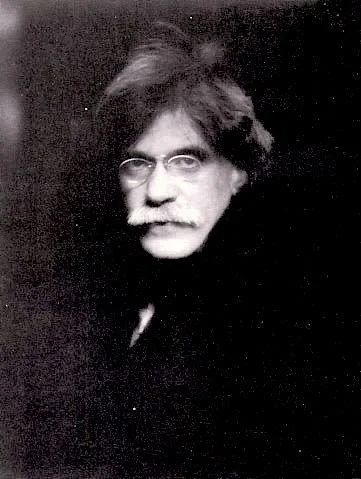

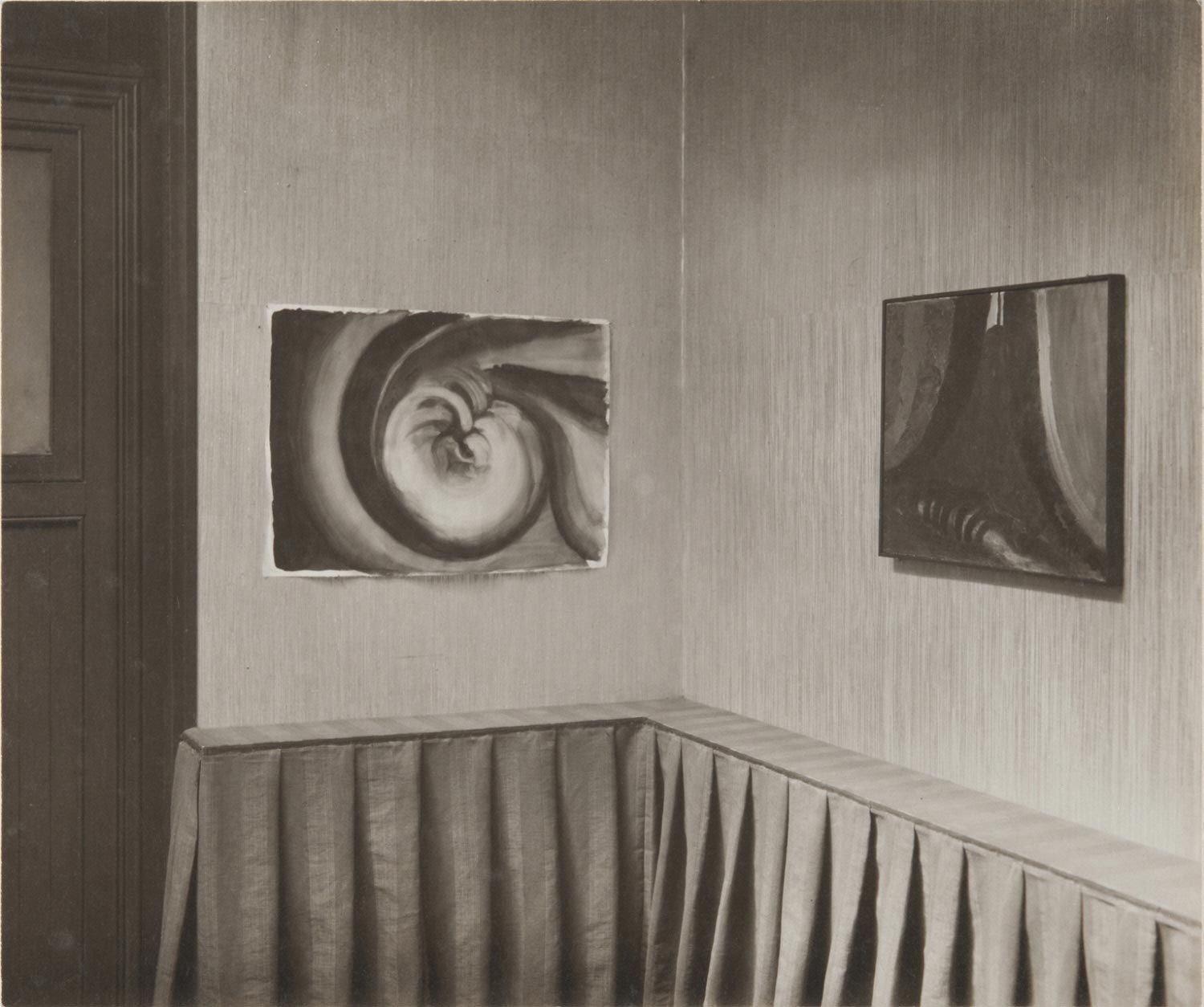

MANHATTAN — January 1916 — Something in the charcoal, its sensuous swirl of black and white, speaks to the photographer. He has worshipped light, captured it, yet he has never seen light and dark like this.

Mr. Stieglitz:

If you remember for a week — why you liked my charcoals that Anita Pollitzer showed you — and what they said to you — I would like to know if you want to tell me. . .

Days later, the photographer replies:

My Dear Miss O’Keeffe:

What am I to say? It is impossible for me to put into words what I saw and felt in your drawings. . . I do not know what you had in your mind while doing them. But I do feel that they have brought you closer to me. Much closer.

Artists work alone. And all too often, even if entwined with someone, they live alone. So when two artists meet and reach out, the world feels them touch.

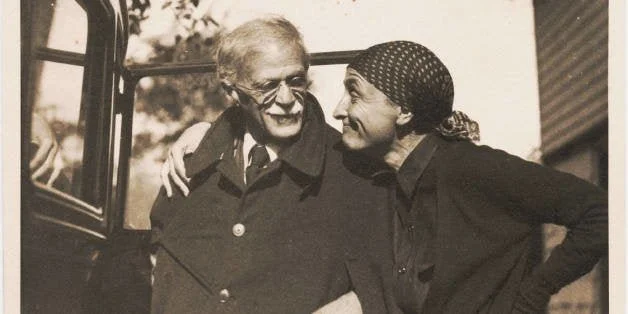

What began with letters became a romance — close-up then long distance — between Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. Over 30 years, the couple wrote more than 5,000 letters totalling 25,000 pages. Often writing two or three times a day, O’Keeffe and Stieglitz shared their insights on creativity, art, life. But even when miles and months apart, they shared love.

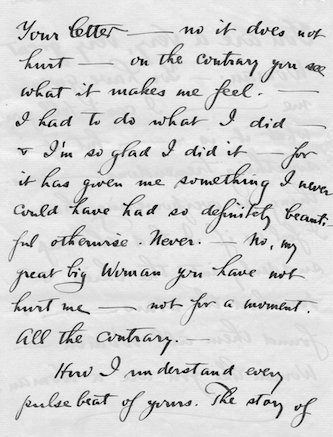

O’Keeffe and Stieglitz “sought to ‘touch the center’ of each other,” wrote Sarah Greenough, editor of My Far Away One. “Their letters were, as O’Keeffe perceptively noted, ‘intensely alive,’ filled with both a great ‘humanness’ and an expansive, generous spirit that made her feel as if ‘all the world greets you.’”

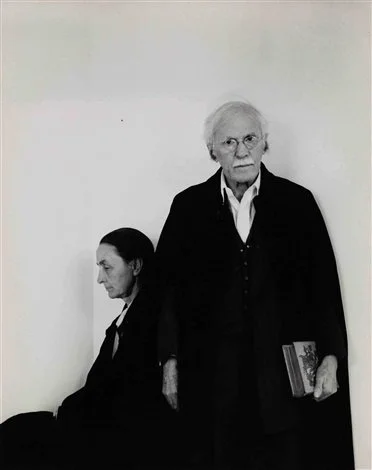

Like chiaroscuro, the juxtaposition of dark and light, Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were studies in contrast. He was urban, son of German immigrants captured by photography in his 20s and dedicated to making it matter. She was rural, daughter of a Wisconsin farm family, aiming to be a commercial illustrator until she was swept into the whirlwind of modernism.

When they met, he was 52, unhappily married. She was 28, a fulltime teacher struggling to find time to paint. But they shared a soliude, a passion for art and soon, for each other.

Writing back, “Miss O’Keeffe” told “Mr. Stieglitz” of her vision.

The uncertain feeling that — some of my ideas may be near insanity — adds to the fun of it.

And as an afterthought:

I put this in the envelope — stretched — and laughed — It’s so funny that I should just write you because I want to — I wonder if many people do. — You see — I would go in and talk to you if I could — and I hate to be completely outdone by a little thing like distance —

Stieglitz kept his reply in his pocket for two days, tore it up, wrote another. She wrote back. He wrote back. When he displayed her charcoals in his gallery 291, she came to Manhattan for the show, then left. Their letters began to simmer.

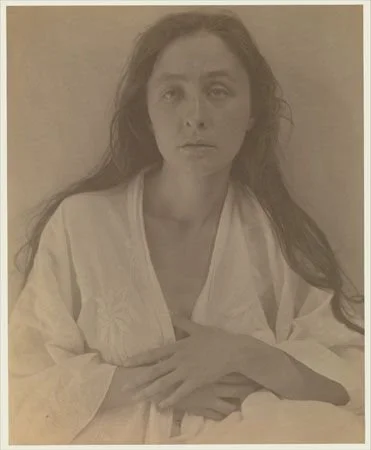

How I wanted to photograph you—the hands—the mouth — & eyes — & the enveloped in black body—the touch of white—& the throat.

Having told you so much of me—more than anyone else I know—could anything else follow but that I should want you?

Within a year, he invited her to move to New York.

Dearest — You are so much to me that you must not come near me — Coming may bring you darkness instead of light — And it's in Everlasting light that you should live.

In 1918, their courtship continued with crosstown letters — she sent him her phone number — but soon came into his studio where he photographed her, she recalled, “with a kind of heat.”

When Stieglitz wife caught them, she threw him out. Within weeks, the two were living together, “like teenagers in love,” one biographer noted. In 1924, when his divorce was finalized, they married. Though the teenage passion went the way of all flesh, their commitment never wavered.

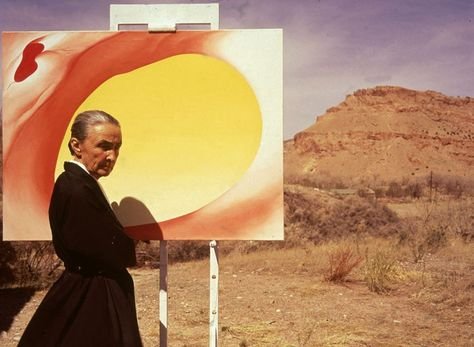

But O’Keeffe tired of Stieglitz family summers in Lake George. She wanted a child; he did not. They quarreled, especially when he had an affair. O’Keeffe later said she put up with “a good deal of contradictory nonsense because of what seemed clear and bright and wonderful.” Then in 1929, she was invited to the high desert of New Mexico.

This really isn't like anything you ever saw and no one who tells you about it gives any idea of it.

Enchanted, O’Keeffe began shuttling beteen Taos and Manhattan. When leaving each spring, she left notes in Stieglitz’ coat sleeves. Once safely apart, they wrote.

He wrote of being “broken” by her departure. She reassured him.

Now listen Boy — I am all right. And what is between us is all right — and I don't want you to worry a bit about me — There was much more cause to worry about things when I was right beside you — If you will just quiet down and be normal I will stay — If you can't — I want you to tell me — But if you can — I want to stay here longer —

While he struggled to recapture his vision, she roamed the high desert — and bloomed. But she always came back to her “faraway one.”

They remained together off and on, like darkness and light, until his death in 1946. Three years later, O’Keeffe moved to New Mexico and spent the rest of her life making its cactus and bare bones her own. Just as she had told him she would.

Please leave your regrets — and all your sadness — and misery — If I had hugged all mine to my heart as you are doing I could not walk out the door and let the sun shine into me as it has. . . A kiss Little Boy — I have not wanted to be anything but kind to you — but there is nothing to be kind to you if I cannot be me — And me is something that reaches very far out into the world and all around — and kisses you — a very warm — cool — loving — kiss —