SCULPTING SILENCE -- THE ASL STORY

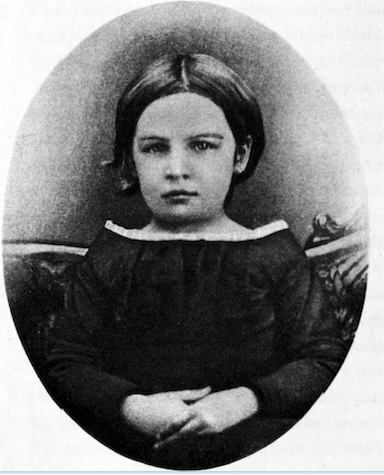

HARTFORD, CT, May 1814 — Alice Cogswell was not born deaf but when she was two, spinal meningitis silenced her world. In the early 1800s deafness was considered a form of mental illness. Lost in their inner sanctum of solitude and silence, no one could possibly teach — or reach — the deaf.

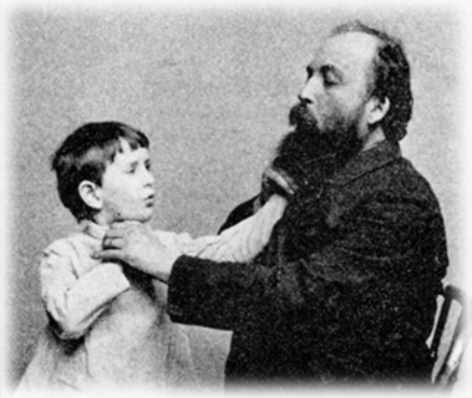

When Thomas Gallaudet moved back into his parents home, next door to the Cogswells, he had no special interest in the deaf. A child prodigy, graduated from Yale at 17, Gallaudet was a pastor without a church, a teacher without a classroom. Adrift and recuperating from strenuous study, Gallaudet was watching Alice one day when he got an idea. Why not use gestures to teach what speech could not?

American Sign Language is something of a miracle. Most nations have several sign languages varying by region, but ASL, mastered by nearly a half million people, is the language of hearing-imparied Americans. And the miracle started not with one man but with one remote town on a remote island.

Perched at the tip of Martha’s Vineyard, Chilmark, Massachusetts is now known for pristine meadows, white sand beaches, and astronomical property values. But in the early 1800s, Chilmark’s signature was silence. Congenital deafness, brought from England by a recessive gene among one family, had spread throughout the tiny fishing town.

Nearly every Chilmark family had a deaf child, parent, or other relative. Not content to live in silence, families communicated with signs that grew more intricate, more expressive by the year. Some signs were based on gestures spread by native Wamapnoags, but most were made up on the spot. And repeated. And shared by deaf and non-deaf throughout Chilmark.

Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL) might have stayed on the Vineyard had Thomas Gallaudet not met Alice Cogswell. But the meeting, and Gallaudet’s skill at teaching Alice by drawing stick figures in the dirt, led the girl’s father to send her teacher to Europe in search of signs.

America had no schools for the deaf but at the Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets a Paris, he saw an entire language spoken by hand. Gallaudet soon befriended two teachers and convinced one, Laurent Clerc, to return with him to America.

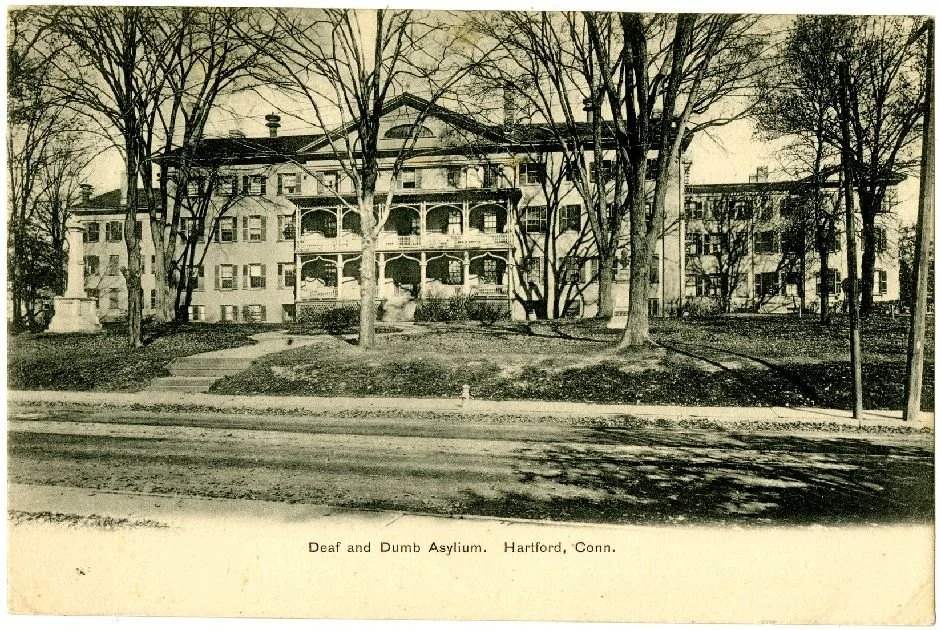

In 1817, Gallaudet and his French muse opened the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons. The first student was Alice Cogswell. Within a few years, more than 100 students were learning French Sign Language. About half those students came from Chilmark, bringing their own signs.

Over the next decade, even as Noah Webster was forging the first American dictionary, Thomas Gallaudet and his students were creating American Sign Language. A hybrid of the French and Martha’s Vineyard systems, with some extra signs added by students from other small deaf communities in New England, ASL broke down barriers and opened worlds of expression. It was also, as we have all since learned, rather beautiful to watch.

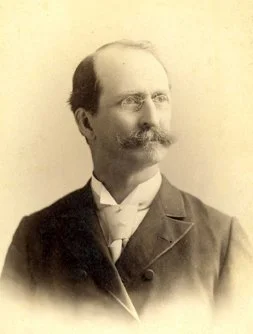

Throughout ante-bellum America, ASL spoke to students at nearly two dozen upstart schools for the deaf. Thomas Gallaudet died in 1851 but his language lived on. A few years before the Civil War, his son, Edward, a teacher at the Hartford Academy, moved to Washington, D.C. to lead a deaf school. During the war, he convinced Congress to fund the first college for the deaf, later renamed Gallaudet College. (And in 1983, Gallaudet University.)

The deaf knew the power of ASL but some thought they knew better. Why go to the trouble of teaching a new language when you could teach the deaf to read lips? “Oralism” put the onus of communication on the deaf and relieved everyone else of learning to sign.

Promoted by the prominent Alexander Graham Bell, oralism soon silenced ASL. In 1880, when a conference of educators in Italy backed lip reading, ASL was banned from American schools for the deaf. Hands were stilled. A language was nearly forgotten. In 1952, the last living speaker of MVSL died in Chilmark. The miracle, however, got a second chance.

William Stokoe, a teacher at Gallaudet University published his dissertation on ASL in 1960 Grammar of Sign Language was to the deaf what Webster’s dictionary was to the rest. Contrary to common wisdom, Stokoe showed, ASL was not just a collection of signs but a fully developed language with its own grammar and syntax.

The battle between signs and lip reading raged for another 20 years. But by the 1980s, ASL had entered mainstream American culture. Speeches, plays, and other spoken words were being “signed” by ASL interpreters. Movies such as “Children of a Lesser God” portrayed deafness not as a “handicap” but as a gateway to another language.

“Forty years after the language gained academic recognition,” Gallaudet University’s website notes, “schools have accepted sign language in the classroom.” Interpreters, deaf actors in Hollywood, and ASL lessons have proliferated online, but the greatest miracle of ASL is personal.

“For some deaf people,” gallaudet.edu notes, the most dramatic change is new pride in using their language in public.”

What has ASL meant to the deaf? “You have to be deaf to understand,” one poet wrote. Another, Robert F. Panara, added:

My ears are deaf, and yet I seem to

hear Sweet Nature's music and the

songs of man, For I have learned from

Fancy's artisan How written words

may thrill the inner ear Just as they

move the heart, and so for me They

also seem to sing out loud and free.