THE MAN WHO CONQUERED THE "RED PLAGUE"

NIGERIA, JULY 1967 — As civil war tears a young nation in two, soldiers stream into the rolling hills and jungles of West Africa. But a killer far more deadly than any army is already here. Vaccinations have begun but the Nigerian government stops the program, letting smallpox take its toll among the rebels. That’s when a young American doctor goes rogue.

Hopping in his Dodge pickup, the doctor drives 350 miles through a war zone. Arriving in Lagos, he finds the government storehouse of smallpox vaxxes. While his colleague distracts a guard, the doctor loads his truck with vaccinations, jet injectors, needles, and hope. Then he sets out across the war zone again.

Unless you read the obits, you probably never heard of Dr. William Foege (prounouced FAY-gee.) But when he died last month, the world lost the mastermind of “the greatest scientific and humanitarian achievement of the past century.”

It was Foege, working with the World Health Organization and the Center for Disease Control, who devised the strategy that eradicated smallpox. The “red plague,” which killed a third of all who caught it, had toppled kings and felled armies. When brought to the “New World,” smallpox killed 80 percent of all Native-Americans. How, then, did a humble minister’s son from Iowa save humanity from this scourge?

Growing up with “an unvarnished, down-to-earth beginning in life,” Foege might have followed his father into the clergy if not for his own medical ordeal. At 15, bedridden by a hip operation, he read about Albert Schweitzer’s mission in Africa.

Foege studied public health at Harvard, then went to Nigeria to work as a Lutheran doctor. There he visited homes where he could smell smallpox at the door. “It was the scent of death.”

Foege was living with his wife and young son in a mud-walled hut with no electricity or running water when he learned of Target Zero. WHO’s worldwide campaign had a radical goal — to eliminate smallpox within ten years.

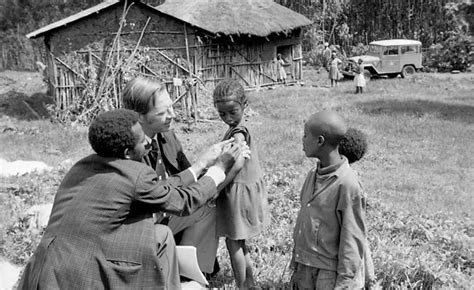

Joining the effort, Foege helped train hundreds to vaccinate everyone within reach. The program was just gaining momentum when Nigeria plunged into civil war.

Surrounded by teenagers who “mixed guns, alcohol, and bravado,” Foege continued his work. With his truck full of stolen vaccinations, he talked his way back into rebel country. But when vaccinations ran low, he needed a different strategy.

Having fought forest fires during his college summers, Foege remembered how blazes were contained by clearing concentric rings to cut fuel supply. With precious vaccines running low, Foege saw the futility of vaccinating everyone. Smallpox, he saw, could be “contained.”

He soon sent 80 percent of his remaining vaccinations to hotspots where smallpox raged, innoculating only family members and contacts of anyone with the disease. The rest of the vaxx was sent “anywhere we thought the virus would go next,” mostly market towns.

“Ring vaccination” met skepticism, but Foege’s 4,000 health workers doubled down on the tactic. Within a year, smallpox was gone from Nigeria. When Foege shared the strategy, WHO adopted it for all of West Africa.

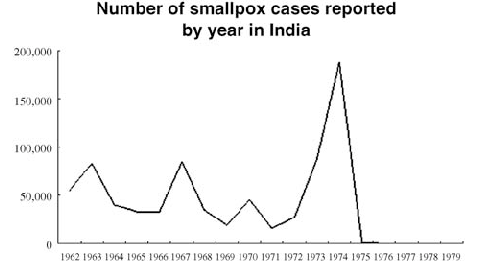

From Nigeria, Foege moved on to India, where he had been a Peace Corps volunteer. Again “ring vaccination” met with skepticism, yet some understood. Foege would never forget hearing one village doctor explain to authorities. When a house is on fire, the doctor said, no one pours water on every house.

“A chill went up my spine,” Foege wrote. “This man condensed all the work, discussions, discoveries and massive human effort of the previous seven months into a few words and the indelible image of a fire.”

A quarter million health workers fanned out across India, using Foege’s method. As eradication neared, he made plans to leave. Asked to stay on, he gave the world a lesson in humility.

“If I remain in India,” he told authorities, “too much attention would be directed toward the external support that India received, and it is very important that recognition be given to the accomplishments of the hundreds of thousands of Indians who really did the work. This is why I am coming home.”

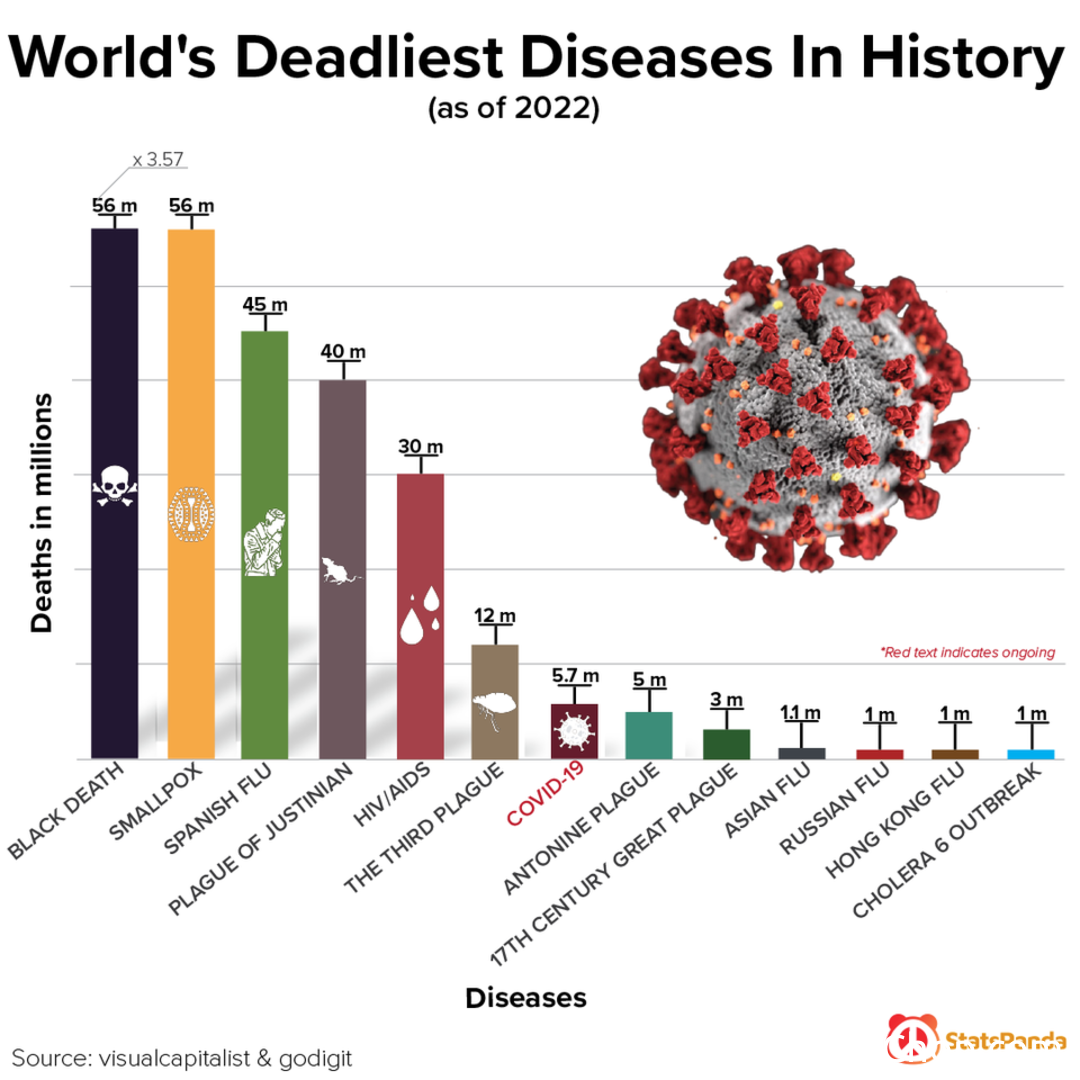

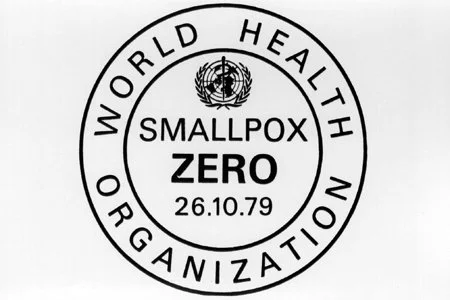

On May 8, 1980, the World Health Organization declared “solemnly that the world and its peoples have won freedom from smallpox.” After claiming nearly 60 million lives, the “red plague” became the only human disease to be wiped off the face of the earth.

Back in the US, Foege headed the CDC under Carter and Reagan, focusing on the “gay cancer” later known as AIDS, then urging that gun deaths and auto accidents be considered public health issues.

Embroiled in politics, Foege championed “science with a moral compass.” He later led worldwide campaigns for child vaccinations. In 1997, when the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation targeted widespread disease in Africa, there was little doubt who they would pick to head their programs.

Dr. Foege, recalled a colleague, “had a special way of cutting through the complexity and scale of the challenges he faced to find the best path forward. Today, countless millions of children are alive thanks to his brilliance and resolve.”

In his final years, as science’s “moral compass” was distorted by magnetic BS, Foege became an outspoken critic. “We’ve broken every rule that we’ve learned on disease control,” he said in 2020. His final op-ed challenged RFK, Jr. whose “track record of nonsense. . . can be as lethal as the smallpox virus.”

Smallpox is gone but the twin viruses of ignorance and gullibility remain. Ever the optimist, William Foege left us with a vision.

“Humanity does not have to live in a world of plagues, disastrous governments, conflict, and uncontrolled health risks. The coordinated action of a group of dedicated people can plan for and bring about a better future. The fact of smallpox eradication remains a constant reminder that we should settle for nothing less.”