TOWARD A HISTORY OF THE FUTURE

“We must get it out of our heads that this is a doomed time, that we are waiting for the end. . . We love apocalypses too much.”

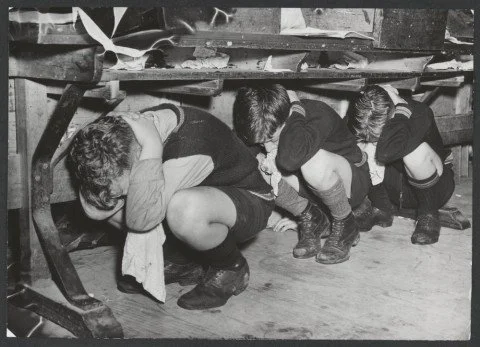

THIRD GRADE — OCTOBER 1961 — We ducked. We covered. We huddled under our desks.

This was not Cuba but Berlin, American and Soviet tanks 100 yards apart at Checkpoint Charlie. We knew nothing of that. We only knew that our teacher, a sunny bleached-blonde we kids called Mrs. Williams, assured us that if an “atomic bomb” hit L.A. we were far enough removed to survive the fallout.

So we lowered the blinds to block flying glass. And we ducked, we covered. And by the time we stood, opened the blinds, and turned on the lights, the future seemed very short.

Even before we third graders were born, William Faulkner had summed up our fates. “Our tragedy today is a general and universal physical fear so long sustained by now that we can even bear it. There are no longer problems of the spirit. There is only the question: ‘When will I be blown up?’”

But here’s the thing. We are still here, most of us.

Armageddon stayed on arm’s length. We survived Berlin, and a year later, Cuba. We even survived the 1980s, as Reagan joked about bombing the Russians. The Eighties best-seller Fate of the Earth, foreseeing a post-nuclear “republic of insects and grass,” turned out to be just a book. Nuclear winter melted into spring. And we are still here.

There’s a cliche about the future, that it comes one day at a time. And yet, since the future first dawned, fear has engulfed it, fear fueled by long looks, often between latticed fingers, at what is to come. Throughout history, except for the century between the telegraph and the bomb, what was to come was most often faced with a shudder. Fire and fate, pestilence, apocalypse soon.

But I have grown skeptical of apocalypse. Having survived the Cold War, having grown up believing we would never make it to 2000 let alone where we find ourselves, I refuse to shine another garish klieg light on the future. I prefer candles.

Yes, I hear the bells tolling. Who can’t? “I’ve seen the future brother,” Leonard Cohen sang, “and it’s murder.” And yes, I know the headlines, the existential threats, the 2020s Zeitgeist best described as “everything sucks, always has, always will. Until —“

“I decline to accept the end of man. I believe that man will not merely endure, he will prevail.”

Yet a new year is upon us, another year we Cold War vets never saw coming. And here we are. Which begs a question. After decades of doom, isn’t it about time we considered that maybe, just maybe, the future holds more than our worst nightmares?

Years ago, CBS’ resident curmudgeon Andy Rooney, who had survived D-Day, said something I’ve never forgotten. After describing America the Worried, Rooney said, “It’s just amazing how long this country has been going to hell without ever having gotten there.”

Yet fear of the future persists. “We are all afraid for the future,” “Ascent of Man” host Jacob Bronowski said. “That is the nature of the human imagination.”

But our imaginations have a parallel nature and it also has a long history. Call it hope, mock it as Pollyanna, tell it to get it’s head out of the sand, but it’s still there — the lingering suspicion that when we routinely recoil from the future, we are cheating each other. Consider science fiction master Octavia Butler.

Butler, another survivor of duck-and-cover, offered four tips for predicting the future. The last was “Count on the Surprises: No matter how hard we try to foresee the future, there are always these surprises. The only safe prediction is that there always will be.”

You’d have to wear glasses of a certain color to see the world to come as bright and beckoning. There will be flying glass. There will be fallout. Yet we have a responsibility to face the future — full on, eyes forward, no ducking or covering.

This month The Attic will focus on the future, not the techno-future of AI and robo-cars, but the future as it used to be. Hopeful. We’ll sample from the world’s time capsules. We’ll fly in an amazing airship built by boy genius Tom Swift. We’ll drop in on the Long Now Foundation that stretches our vision beyond the next few decades and into the next few millenia. And at month’s end, we’ll rise from the floor, turn on the lights, open the blinds, and enter a future that’s more than “very short.”

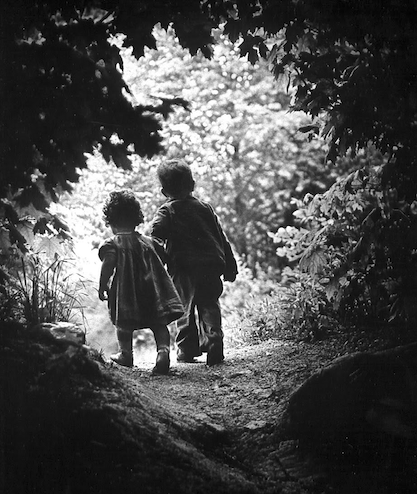

Last month, a remarkable thing happened in my town. Just down the street, in a house I pass every day, a newborn baby came home from the hospital. A boy. I’ve seen him once. There he was, head thrown back, cheeks plump and red, tiny fingers reaching out to grasp time itself.

Given a normal lifespan, my new neighbor will live into the 22nd century. We don’t know what he will see nor what the world will be like. Everyone reading this will be gone, that much we know. And that our departure will leave the future we dread to the ones just awakening now. Don’t we owe that future, and the children who will make it, a brighter path?