CELEBRATING SCHLOCKY SENTENCES

SAN JOSE, CA, 1982 — It was a trite and crappy sentence.

And Scott Rice had read enough. One afternoon during a bull session with fellow English professors at San Jose State, Rice recalled his grad school research into literature’s most infamous opening sentence.

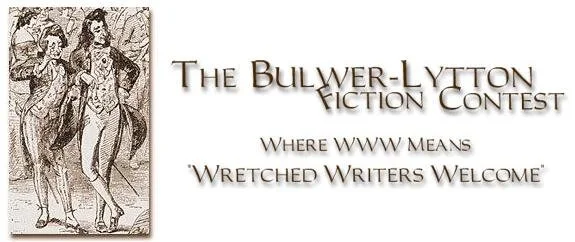

Turns out that “It was a dark and stormy night” did not spring from the typewriter of Snoopy sitting on his doghouse. “Dark and stormy” was penned by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, a Victorian novelist whose popularity once rivaled that of Dickens. So, Rice wondered, if triteness could gull readers back then, why not a contest “to compose the opening sentence to the worst of all possible novels?"

The Bulwer-Lytton Literary Contest kicked off in 1982. Limited to the SJSU campus, the contest drew just three entries. But in the age of Sidney Sheldon (The Other Side of Midnight) and Jackie Collins (Hollywood Wives) readers and writers were desperate to dance along the dicey divide between polished prose and sheer shlock. (Okay, no more of that.)

In its second year, when Rice’s contest was featured in People, 3,000 entries poured in. Rice, who grew up in Idaho enthralled by his grandparents’ pioneer stories, had struck a nerve. “I’m like a man who was drilling for water and hit oil. People really put thought into it. They enjoy a contest in which there’s no pressure to be ‘the best.’”

Just how bad could bad prose be? Though only one entrant submitted an air-sickness bag with a sentence, most should have. Because:

— “Dawn broke like a crusty suet pudding.”

— “Grimelda’s heart was on the ship with Lord Touchnot.”

— “The rising sun crawled over the ridge and slithered across the hot barren terrain and to every nook and cranny like grease on a Denny’s grill on the morning rush. But only until 11 o'clock when they switch to the lunch menu.”

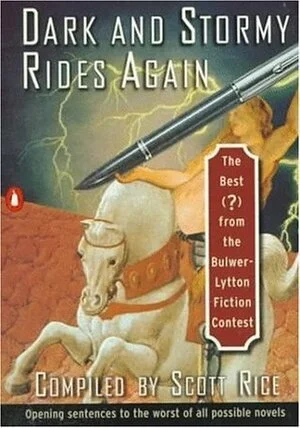

By the 1990s, the Bulwer-Lytton Contest was drawing 10,000 entrants per year. Rice added new categories — detective novels, romances, Westerns, and “purple prose.” Five books of the best/worst opening sentences, including Grand Prizes and Dishonorable Mentions, sold well. And Bulwer-Lytton had stiff competition.

From its debut as a “promotional gag,” the Harry’s Bar & American Grill Imitation Hemingway Competition also rose like, well, the sun. Never mind that Hemingway hated parodies, calling them “what you write when you’re associate editor of the Harvard Lampoon.” Hem knew that “the greater the work of literature, the easier the parody.” And from its start, the Imitation Hemingway contest reveled in “bad Hemingway,” including my own entry “A Moveable Feast,” which had Hem hunting his steak through the wilds of Harry’s Bar. Others included:

— “He stepped close and jammed his clenched fist downward on the rusted urinal handle as if he were jamming the beak of a muleta into the damp muzzle of a bull.”

— “He could taste death in the wind. He could hear it tiptoe around the campsite. He could see it climbing a tree, hiding in a garbage can, tripping over a roof. . .”

In the age of Sidney Sheldon and Jackie Collins — and let’s not forget Tom Clancy — the Hemingway contest proved as popular as Bulwer-Lytton. Hundreds each year submitted “one really good page of really bad Hemingway.” Distinguished judges included George Plympton, Ray Bradbury, and Hemingway’s son Jack. TV cameras caught judges at Harry’s Bar poring over entries, trying as Bradbury noted, “to separate the good bad Hemingway from the bad bad Hemingway.” The winner was often read aloud to toasts and shouts of “ole!”

Soon it was Faulkner’s turn. “Bad Faulkner was everywhere, like no-seeums on a beach in July,” wrote Faulkner’s niece Dean Faulkner Wells. So when the American Way inflight magazine teamed with the Faulkner Newsletter, Wells remembered, “the would-be Faulkners came roaring in from three continents like bonsai Bundrens waving their sheets of misbegotten prose and shouting that theirs was the best bad Faulkner in the world.”

Mocking Hemingway proved easier than spoofing Faulkner, whose windy prose sometimes seems to parody itself. But faux Faulkner titles were fun. ”As I Lay Dieting.” “The Round and the Furry.” “Inclusion in the Rust.” On the sentences flowed, the contests flourished.

Spinning off Scott Rice, the Lyttle Lytton Contest sought the best/worst short opener, 25 words or fewer. The debut winner — “Turning, I mentally digested all of what you, the reader, are about to find out heartbreakingly” — led to more.

— “John, surfing, said to his mother, surfing beside him, ‘How do you like surfing?’”

— “The sorrowful sun sank into the tears that were the waves, and Sammy, too, began to cry a bit.”

— “‘Clang! Clang!’ protested the knights’ swords, as they were each stopped by the metal wall of the other.”

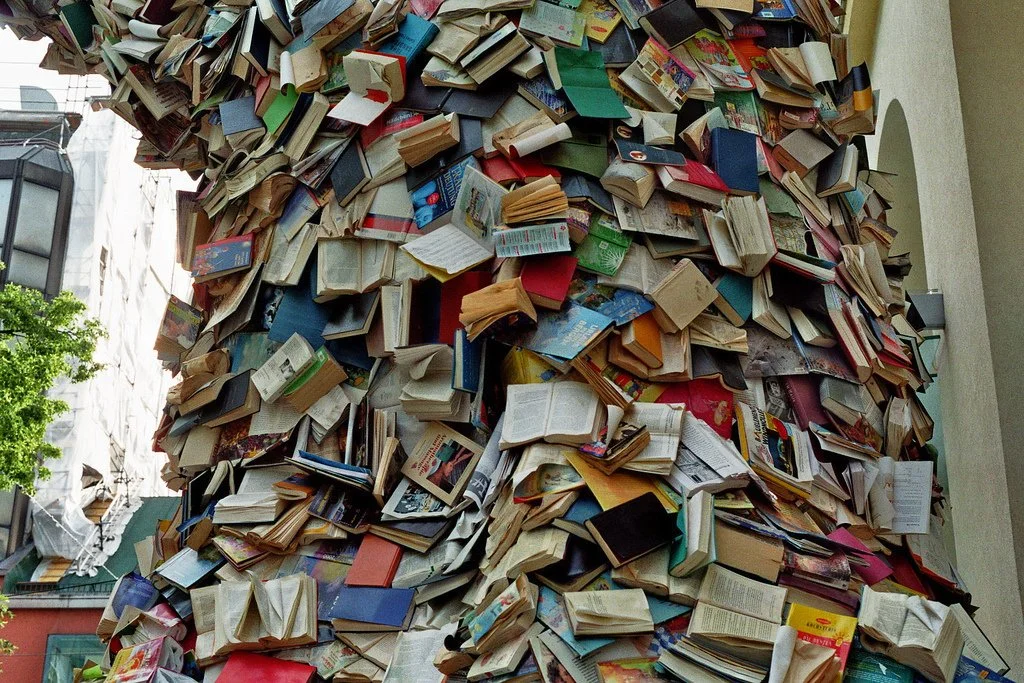

The Lyttle Lytton Contest is, alas, the only one of the above still up and running. Submit your own schlocky sentence here. The Hemingway and Faulkner contests faded in the early 2000s. And Scott Rice, despite help from his daughter (above), regretfully closed the Bulwer-Lytton contest last summer. Archives of all winners remain online.

With the contests gone, trite and crappy sentences have moved, en masse, to actual books, including the 2.6 million now self-published each year. Edward Bulwer-Lytton, who also coined the phrase “the pen is mightier than the sword,” would have been proud.

“We all like to think that we're being clever with these things," said Bill Crowley, 2002 Bulwer-Lytton winner. "And even though it's called bad writing, which it surely is, there are actually people who make their living doing this."