THE WELL-BEHAVED WOMAN BEHIND 'WELL-BEHAVED WOMEN...'

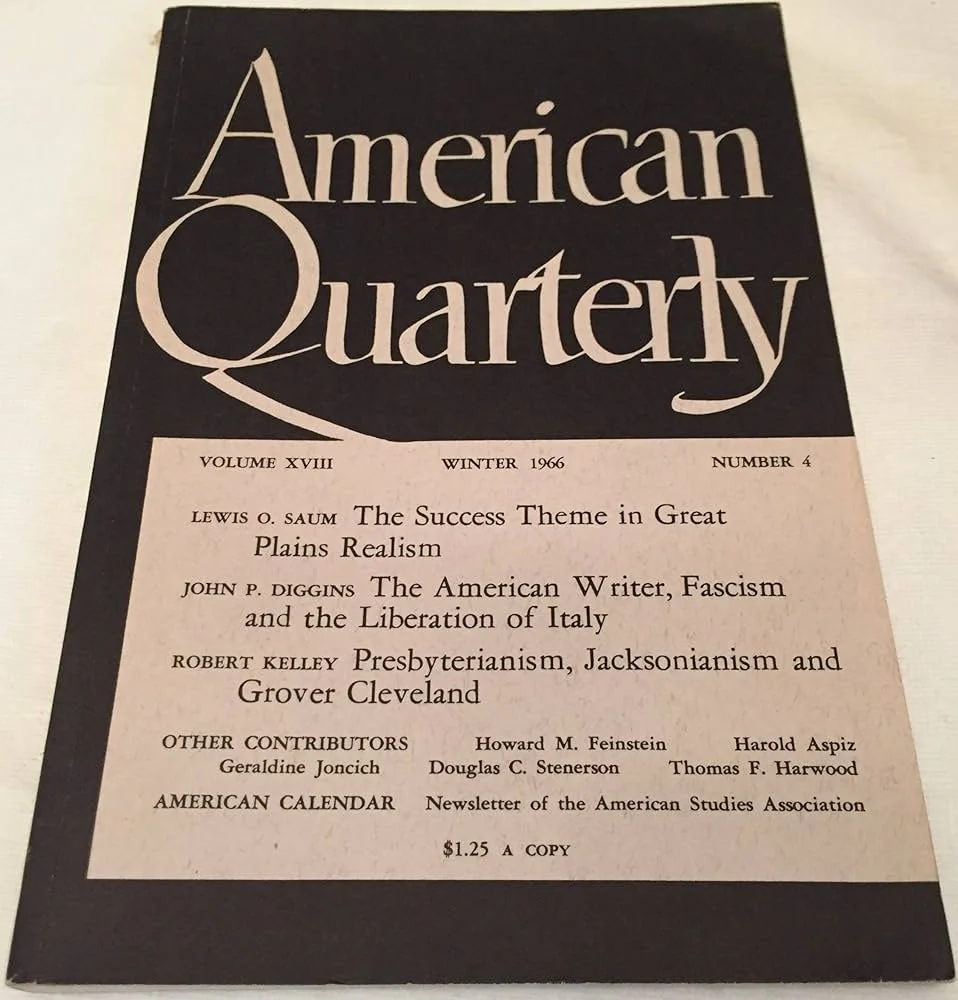

ACADEMIA — SPRING 1976 — Comes now another journal, another dozen dull monographs. Look, here’s a really fascinating article in American Quarterly.

“Virtuous Women Found: New England Ministerial Literature 1668-1735.” From the opening paragraph: “They prayed serenely, read the Bible through at least once a year, and went to hear the minister preach even when it snowed. Hoping for an eternal crown, they never asked to be remembered on earth. And the haven’t been. Well-behaved women seldom make history.”

Chances are you know that last phrase. You may have seen it on: bumper stickers, mugs, greeting cards, plaques, T-shirts, tote bags. . . But chances are you don’t know the well-behaved woman who, as a 36-year-old grad student and mother of five, changed women’s history.

“In my scholarly work,” Laurel Thatcher Ulrich wrote, “my form of misbehavior has been to care about things that other people find predictable or boring.”

Born in a tiny Idaho town during the Depression, daughter of devout Mormons, Ulrich was raised to be a good wife. She finished college, married a future professor, and settled down to raise kids. After her fourth child, however, she returned to grad school.

“I didn’t expect to have a career. For me, history was still a kind of hobby.”

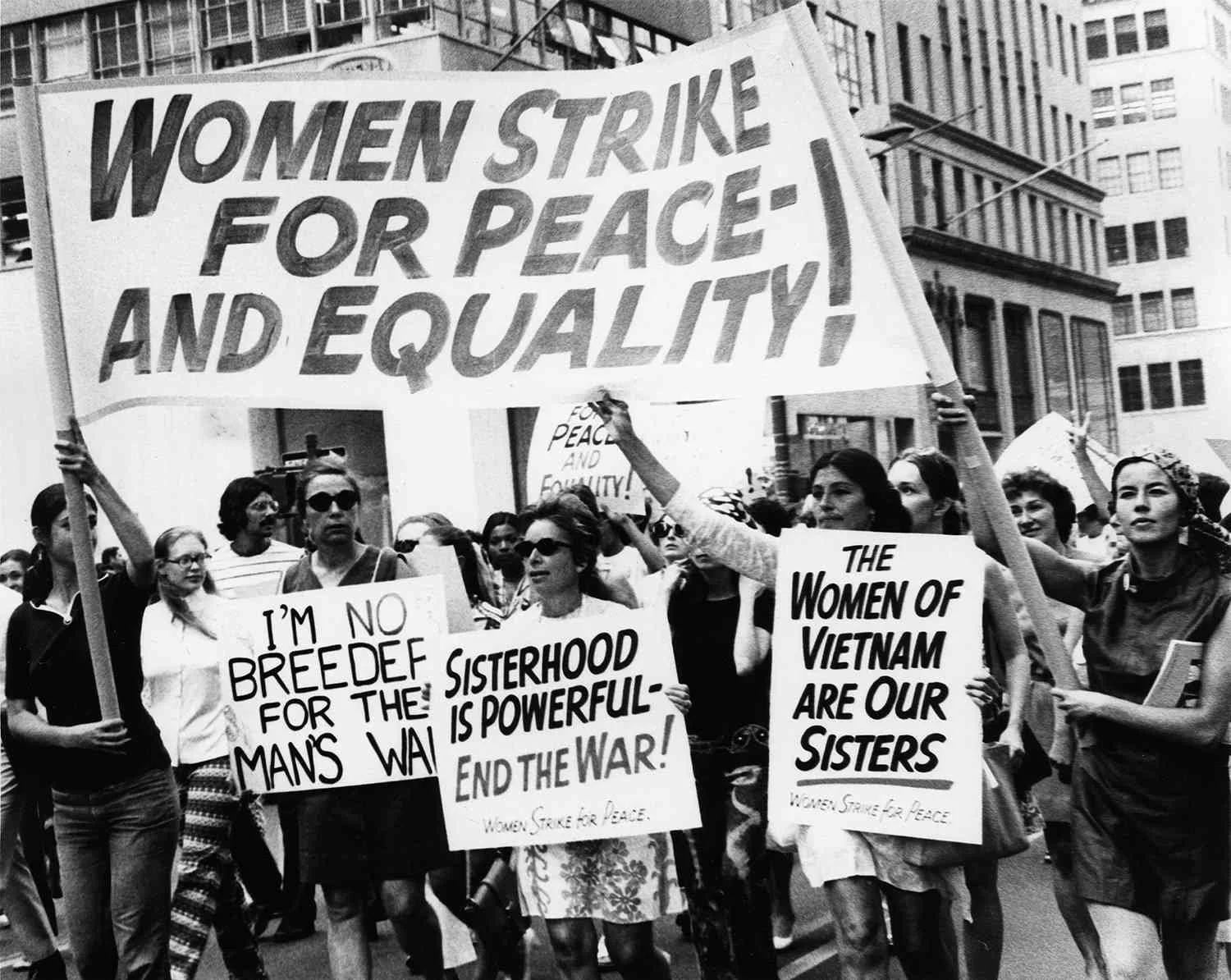

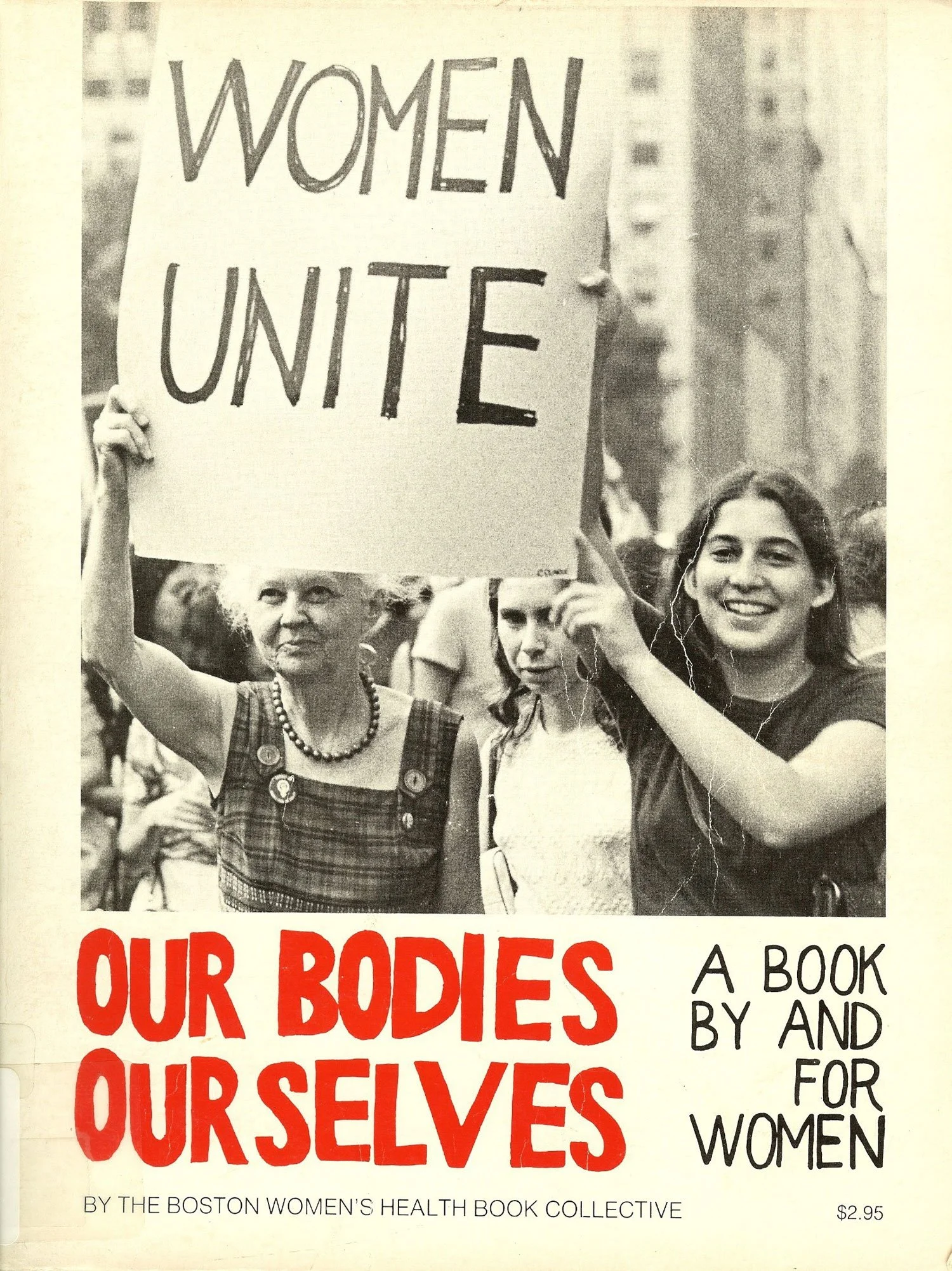

In the 1970s, women’s history was an open and fertile field, yet few historians cared about colonial women. Fewer still wanted to simply tell their story. “My objective was not to lament their oppression,” Ulrich wrote, “but to give them a history.”

By the time Ulrich earned her Ph.D., her first published article with that curious quote was buried in the stacks. But while teaching, she was on the trail of the book that would make her name.

In the summer of 1982, researching a colonial court case, Ulrich drove from her New Hampshire home to Augusta, Maine. After finishing with court records, she visited the state library to find two diaries she’d seen in a bibliography. One was just ten pages; the other held a human life.

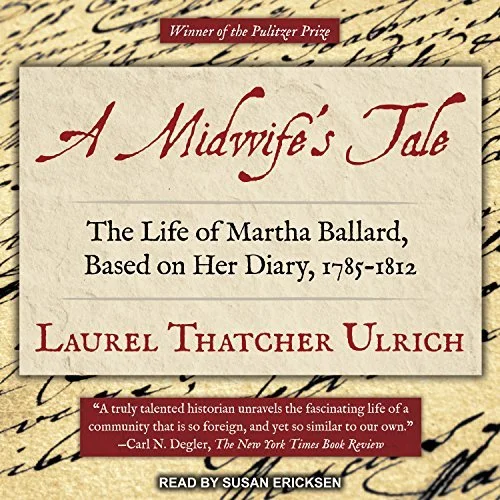

The “two fat volumes bound in homemade linen covers” contained the diary of a midwife, Martha Ballard. Ulrich struggled to read the ink-stained pages and marveled at the world they revealed. Martha Ballard knew the heart and soul of colonial New England. She attended weddings, an autopsy, a rape trial. She saw her husband jailed for debt. She wrote about a mass murder in her town. And, using a blend of herbal medicine and midwifery, she helped to birth more than 600 babies.

Ulrich spent nine years writing A Midwife’s Tale. Published in 1991, the book struck a nerve. Here was “ancient history” that spoke to modern women. Here was an “ordinary woman” rescued from the dusty archives of time.

"It takes a historian of extraordinary persistence, skill, and empathy to recognize Martha Ballard's diary as something of a buried treasure,” the Philadelphia Inquirer wrote. “Ulrich has recognized Ballard's great spirit, and has given to us the gift of a life worth knowing."

A Midwife’s Talevwon the Pulitzer, the Bancroft Prize for History and several other awards. Ulrich won a MacArthur Genius grant and a chair at Harvard. And somewhere in the stacks, digging in some old history quarterly, some scholar recognized Ulrich’s name, read a first paragraph and. . .

Once “well-behaved women’ appeared in a popular women’s history, Ulrich was besieged by requests for permission to use the quote — everywhere. An Oregon woman wanted to put “Well behaved women” on T-shirts. Ulrich “told her to go ahead, all I asked was that she send me a T-shirt.” The shirts sold by the thousands. Then came an e-mail from a former student.

“You’ll be delighted to know that you are quoted frequently on bumpers in Berkeley.” A nursing home used the quote for its “Wild Women’s Group.” A tennis player at Wimbledon wore it on court. A Misbehaving Women Quilt starred at a quilt show. And the Sweet Potato Queens, a women’s group with nationwide chapters, sang. . .

Well-behaved women don’t drink shots and beers

That’s why well-behaved women bore us all to tears. . .

“My runaway sentence now keeps company with anarchists, hedonists, would-be witches, political activist of many descriptions and quite a few well-behaved women.”

Ulrich was both surprised and fascinated. What made “well-behaved women” go viral? “The ‘well-behaved women’ quote works because it plays into longstanding stereotypes about the invisibility and the innate decorum of the female sex.”

But the stereotype, she added, “limits women. It also limits history.” Until the 1970s, few women made history by writing it, but all women made history by living it. Their lives and contributions just have to be discovered — and honored.

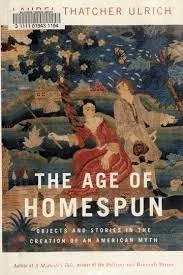

Since A Midwife’s Tale, books about “ordinary women” have taken women’s history beyond its pantheon of Eleanor Roosevelt, Marie Curie, Rosa Parks. . . Ulrich has written about women’s work with “homespun” objects, about Mormon women, and about “well-behaved women” from Virginia Woolf to Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

“Sometime in my thirties I discovered that writing about women’s work was a lot more fun than doing it.”

Now retired, Ulrich still can’t get over how a single line, written in a history journal by a grad student, touched so many lives.

“While I like some of the uses of the slogan more than others, I wouldn’t call it back even if I could. I applaud the fact that so many people — students, teachers, quilters, nurses, newspaper columnists, old ladies in nursing homes, and mayors of western towns — think they have the right to make history.”