OL' DIZ -- AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL

ST. LOUIS, 1934 — During the Depression, baseball was the soul of American sports. There was no NBA. The NFL was small and mostly ignored. Hockey was for Canadians. Play ball!

Unlike today’s multi-millionaires, baseball featured ragtag ruffians with nicknames like Pepper and Rabbit, Gabby and Goose. But there was only one Dizzy.

He was born Jerome Hanna Dean. Or Jerome Herman. Perhaps Jay Hanna. Born in Lucas, Arkansas. No, in Mississippi. Or somewhere else, he told a third sportswriter. “I give ‘em each a scoop so their bosses can’t bawl them out for gettin’ the same story.”

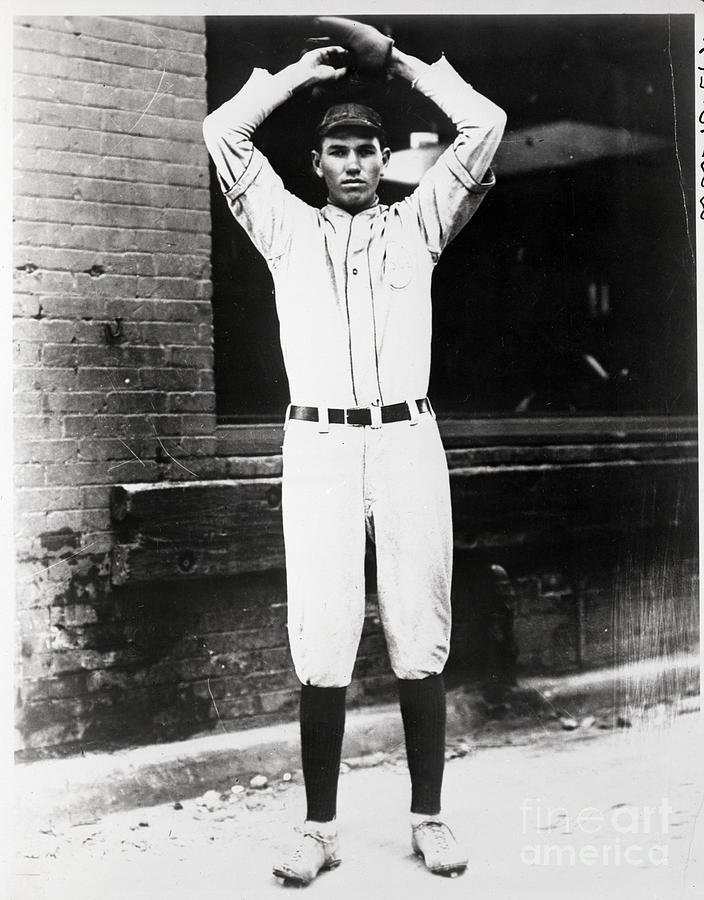

The son of a sharecropper, he spent his childhood picking cotton and throwing dirt clods. He dropped out of second grade, later recalling, “I didn’t do too good in first grade either.” But when it came to throwing a baseball. . .

“As a ballplayer,” sportswriter Red Smith wrote, “Dean was a natural phenomenon, like the Grand Canyon or the Great Barrier Reef. Nobody ever taught him baseball and he never had to learn. He was just doing what came naturally.”

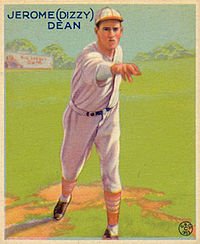

At 19, pitching for an army team, he earned his nickname when an opposing manager told his team to “knock that dizzy kid out of the box.” That year, the St. Louis Cardinals signed him for a $300 bonus. He won 25 games in the minors, then made his major league debut on the last day of the 1930 season, hurling a three-hitter. His manager, who had caught the fastest ever — Walter Johnson — predicted Dean would be “one of the greats. But I’m afraid we’ll never know from minute to minute what he’ll do or say.”

He boasted that he could “pitch the Cardinals to the pennant,” but they sent him back to the minors. After another 25 wins, he returned to St. Louis. Then during a summer of bread lines and bank closures, Dean began dazzling opponents with his fastball and delighting fans with his dizziness.

— “This guy looks mighty hitterish to me.”

— “Boy, they was really scrummin’ that ball over today.”

— “I just rared back and fogged.”

“Ol’ Diz,” as he called himself, won 18 games in his rookie year, 20 the next, setting a strikeout record with 17 in one game. Then came the season and the team of legend — the Gashouse Gang.

“They don’t look like a major league ball club,” the New York Sun observed. “Their uniforms are stained and dirty and patched and ill fitting. They spit out of the sides of their mouths and then wipe the backs of their hands across their shirt fronts.” But, the Sun noted, “they are not afraid of anybody.”

With Ol’ Diz as leader, the gang clowned its way through half the season, building bonfires out of bats and storming hotels dressed as house painters. Then, after Diz held out for more pay, tearing up his uniform — twice so the press could take note — they caught fire.

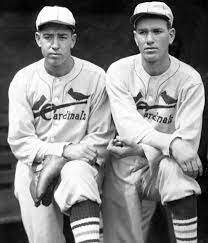

Down the stretch, Diz carried the team. On September 21, he won the first game of a double header. His brother Paul won the second, throwing a no-hitter. “Shoot!” Diz said. “If I'd a known Paul was gonna pitch a no-hitter, I'd a pitched me one, too!"

Today’s pitchers rest four days between games and rarely last nine innings. But Diz came back two days later, relieving in both games of another twin bill. Two days after that, he started and threw a shutout. Two days later, another start — another shutout. And two days on, a third shutout. Ten days — four starts, four wins, bringing his season total to thirty, a magic number no National Leaguer has equalled.

Diz asked to start every World Series game, predicting he’d win four of five, but he had to share the spotlight with Paul. Each Dean won two games, making the Gashouse Gang world champs. They were also “America’s Team.”

As baseball’s most western team, the Cardinals’ broadcasts and fans spread across the South and Midwest. “Cardinal nation” they called it, with Dizzy Dean as its de facto president.

In 1935, Dean won 28 games, then another 24. At age 27, he seemed destined for 300 wins, but during an All-star game, a line drive smashed his big toe. Told it was fractured, Dean said “Fractured hell, the thing’s broken.”

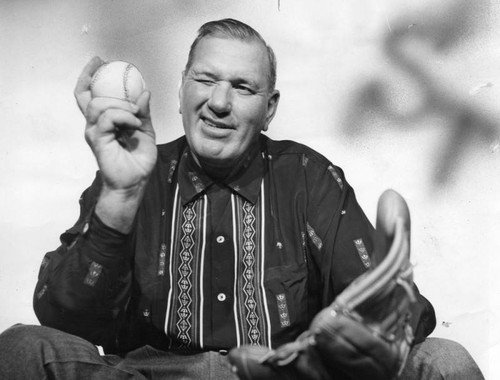

Diz came back, but too soon. Favoring his foot, he ruined his golden arm. He won just 16 more games, retiring at 31. But he wasn’t done yet. As fast a talker as a pitcher, Dean spent a quarter century in the broadcast booth. His fractured language kept fans listening.

— “He shouldn't hadn't ought-a swang!"

— After a foul ball, “the players returned to their respectable bases.”

— Signing off — “Don’t fail to miss tomorrow’s game!”

When English teachers protested his use of “ain’t,” Dean quoted Will Rogers. "A lot of folks who ain't sayin' 'ain't,' ain't eatin'. So, Teach, you learn 'em English, and I'll learn 'em baseball."

On into the 1950s, Diz was America’s announcer, gregarious, unpredictable, eventually enormous. Golfing with Eisenhower, he explained how he got so fat. “I’ll tell you how it was, Mr. President. For the first 20 years of my life, I never had enough to eat, and I ain’t caught up yet.”

By the time he died in 1974, baseball was a rich man’s game. Gone were the days of Gabby and Goose and the Gashouse Gang. But Diz was fondly remembered.

Along with being in Baseball’s Hall of Fame, his brashness made him the precursor of swaggering stars from Muhammad Ali to Joe Namath to every last player in today’s NBA. All seem to embody Dean’s motto: “It ain’t braggin’ if you can do it.”