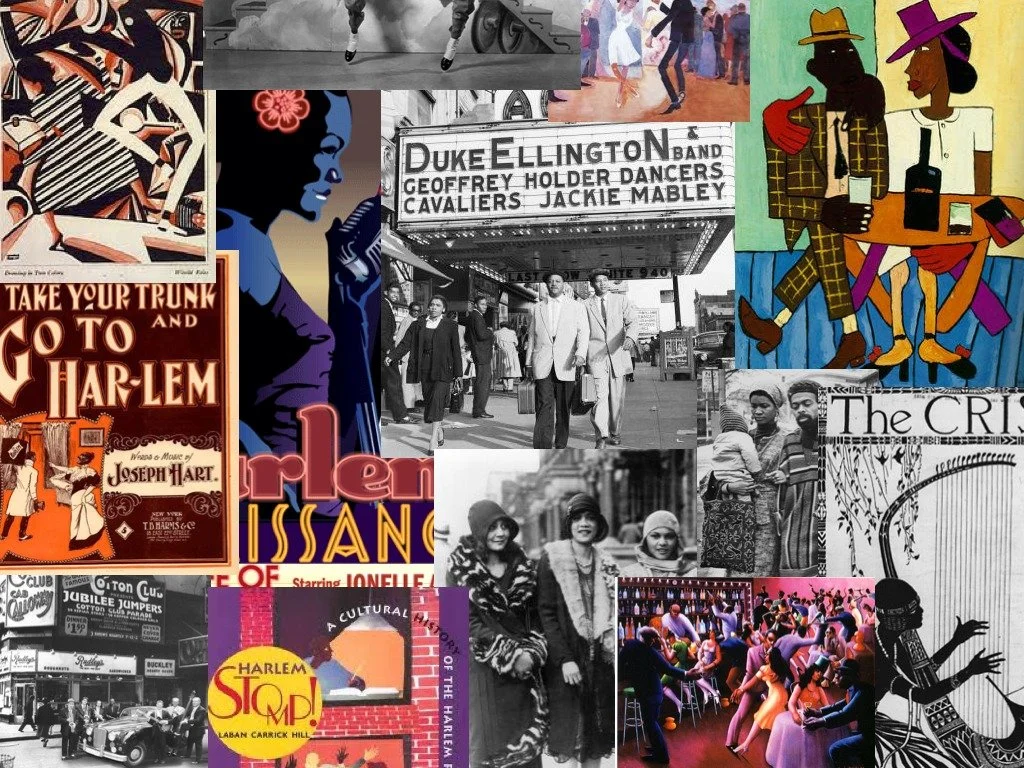

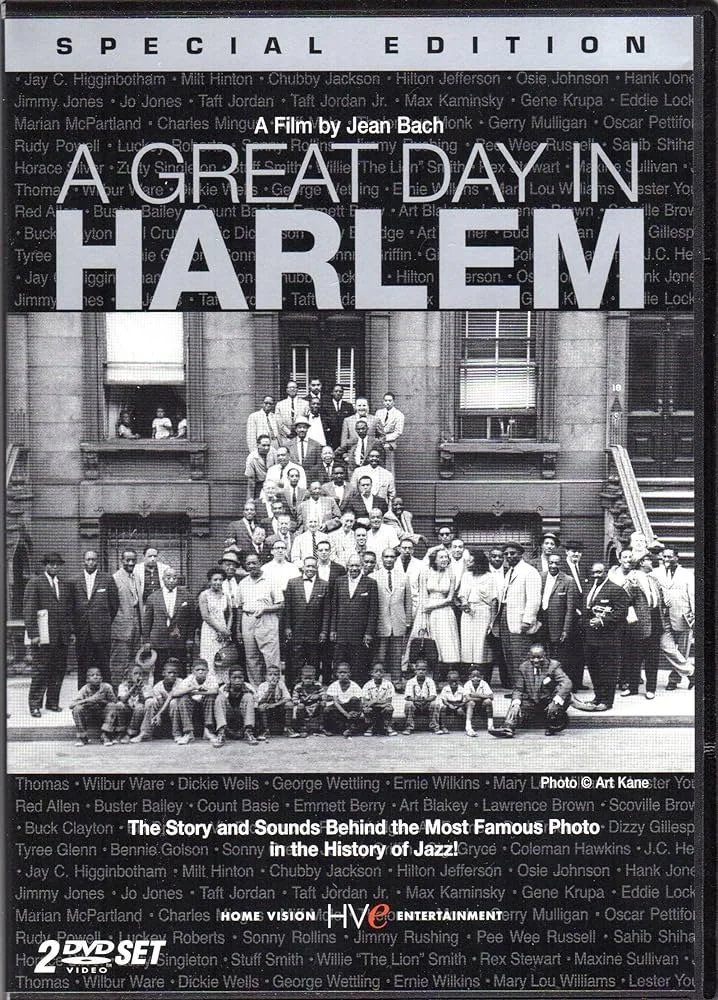

GREAT DAY IN HARLEM

HARLEM, August 12, 1958 — On a sultry summer morning, the long stretch of apartments lining 126th Street is quiet. Police have blocked off the street, leaving just a few kids playing on the pavement, others shouting from open windows. And then at 10 a.m., Jazz comes calling.

One-by-one, musicians stroll down the sidewalk, each stopping at the steps fronting No. 17. The musicians, late night denizens of Manhattan’s burgeoning jazz scene, have not been out so early in years. One says he “didn’t know there were two ten o’clocks each day.”

In suits and ties, sport coats and slacks, sunglasses and the occasional porkpie hat, the crowd begins to mingle. A few jazz newcomers are on hand, but most are already legends. The list includes:

Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Gerry Mulligan, Charles Mingus. . . And no one knows who will show up next. Because this truly is “a great day in Harlem.”

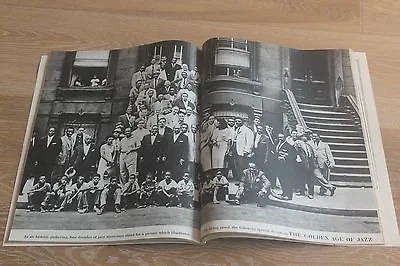

“The most iconic photograph in jazz history” was, like jazz itself, an improvisation. Two dreamers at Esquire, needing a photo for their Golden Age of Jazz issue, decided to take a chance.

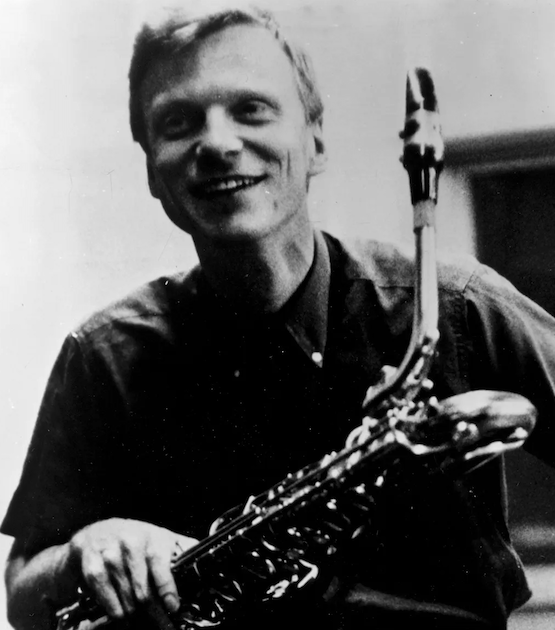

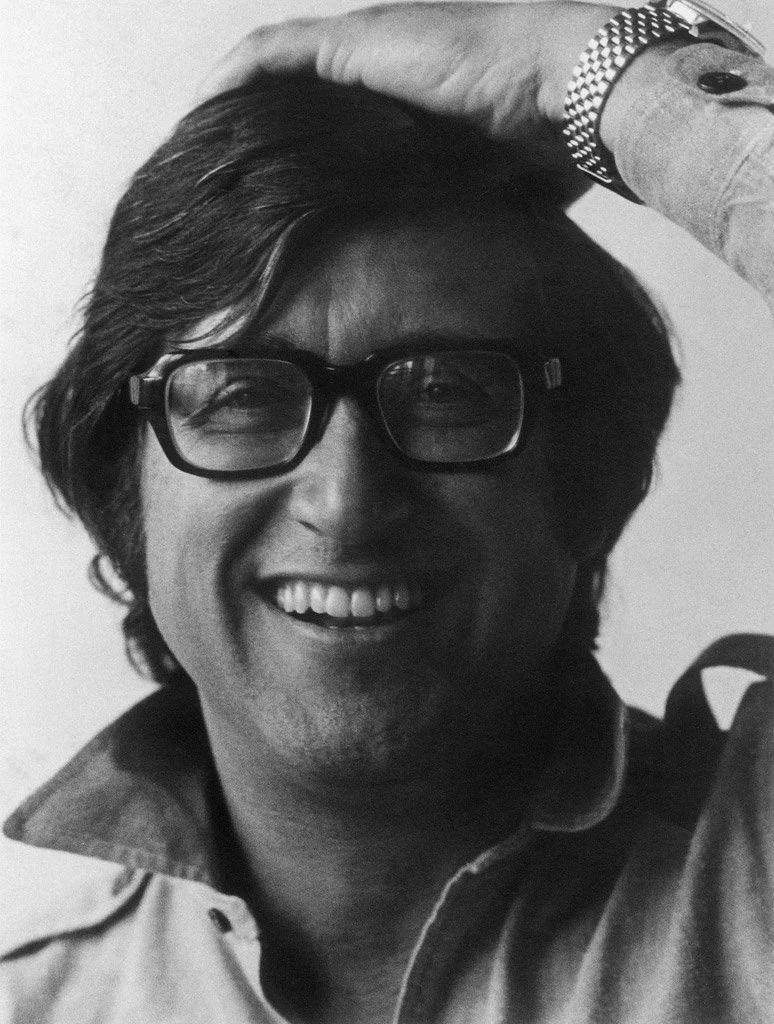

“I was new enough and dumb enough in those days that I was willing to try all sorts of risky things,” recalled Robert Benton (above left), Esquire graphics director. The magazine’s young art director agreed. Art Kane suggested “getting together every possible jazz musician we could possibly assemble.”

But herding jazz musicians was like herding cats. Cool cats, that is. Fiercely independent night owls, the men and women who had taken jazz from Dixieland on to Fifties bop and be-bop seemed unlikely subjects for a group photo. Still, Benton and Kane decided to try.

”It would be sort of a graduation photo of all the jazz musicians,” Kane said. “After I thought about it some more I decided they should all get together in Harlem. After all, that’s where jazz started when it came to New York.”

Contacting club owners, the musicians’ union local, recording studios, and songwriters, Kane sent an open invitation with time and date. 10 a.m. August 12. Benton expected a dozen musicians might show. But here they came. . .

Louis Armstrong couldn’t make it. On tour. Likewise Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Billie Holliday. And Charlie Parker had slid over the edge a few years back. But Sonny Rollins showed up. And drummer Gene Krupa, saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, pianist Mary Lou Williams. . .

“What we called the big dogs — the giants were there,” one remembered. And within moments, the impromptu gathering became “a family reunion.”

“How ya doin’, baby?”

Hand slaps, shakes, shoulder hugs. Children scurrying among the legends, one grabbing Count Basie’s hat. Kids shouting from windows. The band playing on.

“How you been. . .”

“Long time, long time. . .”

After twenty minutes, Art Kane worried. Though a rising star in magazines, this was to be his first photograph for publication. How would he ever get everyone into one photo?

“I never felt so alone in my life, standing across the street, watching my heroes with awe.”

Next came young musicians, yet to make a name. “There was going to be an unusual shooting of a photo for Esquire Magazine, tenor sax player Benny Golson remembered. “And I was being invited to be a part of it. I couldn’t believe it. Nobody really knew me that early in my career. But zippo, I was there on the intended date. When I arrived, there were all my heroes.”

Lester Young, Art Blakey. . . And was that Thelonious Monk behind those shades?

“Monk, how ya’ doin?” Silence. Cool. By 10:30, Kane knew he had to herd the cats — somehow. Grabbing a New York Times, he rolled it into a megaphone and began shouting.

“Please please can you form some kind of a formation, move up to the stops of that brownstone. . .”

The legends thought still talking, vamping, jamming, soon obliged. Some climbed the steps, others stood their ground. As loyal band members, most fell in with fellow instrumentalists, saxmen beside saxmen, drummers beside drummers. . . Count Basie, still wondering about his hat, sat on the sidewalk beside a dozen kids crashing the photo.

Holding a small Hasselblad, Kane took one shot. And another. The musicians soon scattered into Manhattan, but the moment was preserved, and published the following January. A Great Day in Harlem.

Jazz fans cherished the photo but the rest of the world forgot. Benton went on to write Oscar-winning screenplays, including “Kramer vs. Kramer.” Kane became a portrait photographer with work in MoMA and The Met. And jazz just played and played.

Then in 1994, a documentary recaptured that morning, that moment. Most of the legends had passed on but Golson, Blakey, and others trotted out memories, photos, even 8 mm movies of the arrival, the mingling, the magic.

Nominated for an Oscar, “A Great Day in Harlem” sparked more great days. “A Great Day in Philadelphia” and another in Kansas City gathered each city’s jazz musicians for a group photo. St. Paul followed, then Houston. “A Great Day in Hip-hop” was topped by “The Greatest Day in Hip-Hop” featuring 177 hip-hop artists in one frame.

Herding musicians is still a thankless job, but seeing all that talent in one spot is worth the effort. And no great day has yet topped the original. Documentary narrator Quincy Jones explained why. Seems it wasn’t just about the music.

“Black and white, two colors forbidden to be in close proximity, yet captured so beautifully within a single black and white frame. The importance of this photo transcends time and location, leaving it to become not only a symbolic work of art but a piece of history.”