TV'S FINEST DIMENSION

THE COUNTRY OF TELEVISION — Sept. 29, 1961 — With the Cold War on the brink in Berlin, Americans are digging for survival. Can a backyard fallout shelter offer hope?

“All autumn, the chafe and jar of nuclear war,” the poet Robert Lowell writes. “We have talked our extinction to death.” But in “the vast wasteland,” Armageddon was invisible. And then one Friday night. . .

Dr. Bill Stockton’s birthday party is cut short by an air-raid siren. Families scurry into the night, but Stockton has a “bomb shelter.” Safe inside, he hears neighbors pounding, demanding to be let in. The “nightmare” unfolds as neighbor turns on neighbor. Finally, another siren. All clear. Life can go back to normal. But after such raw ugliness, will it? Cut to voiceover. . .

“No moral, no message, no prophetic tract, just a simple statement of fact: for civilization to survive, the human race has to remain civilized. Tonight's very small exercise in logic. . . from the Twilight Zone.”

Through five seasons of the stupidest TV ever to blot American culture, one writer brought compassion, irony, and possibility into our living rooms. “The Twilight Zone” never drew a huge audience, but critics swooned.

“The only show on the air that I actually look forward to seeing — Chicago Daily News

Like Ray Bradbury, Rod Serling was a fount of stories. Of the 156 Twilight Zone episodes, Serling wrote 92. Some were melodramatic, a few silly. But others, still watched, remain “the best that has ever been accomplished in half-hour filmed television." — Variety

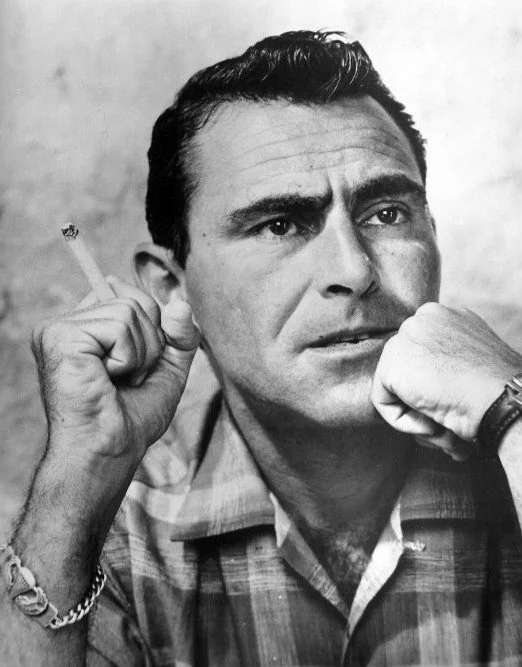

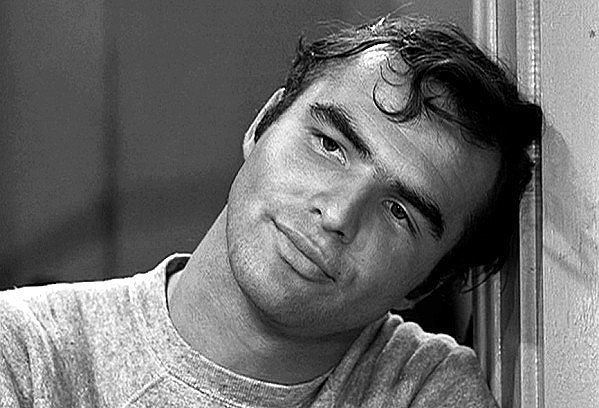

The son of a grocer, growing up short (5’4”) and feisty, Serling fought his way through life. Enlisting in the Army after high school, he took up boxing, became a paratrooper, helped liberate the Philippines and saw half his regiment killed in action. “I was bitter about everything and at loose ends when I got out of the service. I think I turned to writing to get it off my chest.”

During college, Serling sent scripts to radio stations. All but a few were rejected. Then with TV emerging, he was hired by a Cincinnati station. “The minute you tie yourself down to a radio or TV station, you write around the clock. You rip out ideas, many of them irreplaceable. They go on and consequently can never go on again. And you've sold them for $50 a week.”

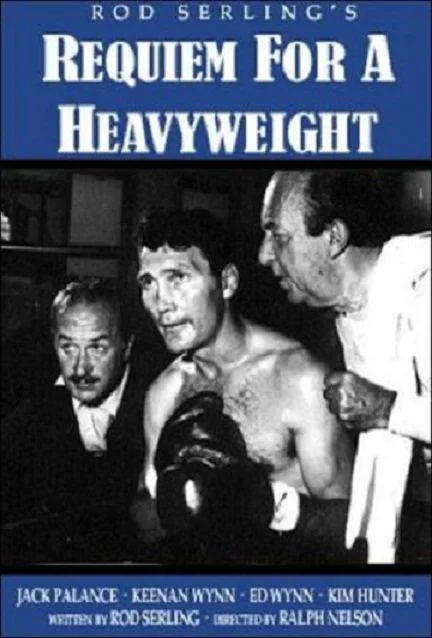

In the mid-1950s, Serling broke through. His gritty teleplay about a punch drunk boxer, “Requiem for a Heavyweight,” won TV’s first Peabody. “And the phone just started ringing and didn't stop for years."

But TV was timid. Sponsors cut the slightest controversy. When Serling’s script based on Emmett Till was re-written to feature a Jewish victim, he was livid. "I don't want to fight anymore,” he said. “I don't want to have to push for something that I want and have to settle for second best.” He wanted his own show.

In 1959, CBS bought Serling’s pilot about a Pearl Harbor vet’s nightmares. In its first season, “The Twilight Zone” aired 36 episodes, 30 written by Serling. Then as TV’s “golden age” devolved into the age of “The Beverly Hillbillies” and “My Favorite Martian,” Serling became an island of integrity and intelligence. And his somber voice gave his show an eerie anchor. Watch:

“The Twilight Zone” took you to other planets, even asteroids. Beyond sci-fi, it took you into the fevered minds of criminals, the innocent hearts of the condemned, the fears of ordinary people.

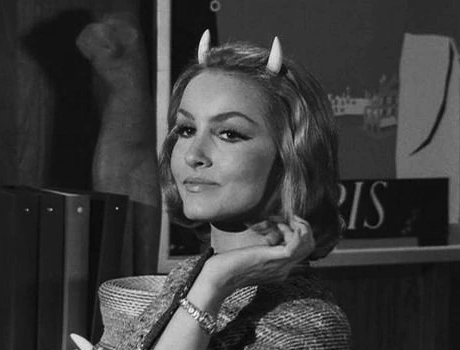

“This is Miss Liz Powell. . . Enter one Paul Driscoll, creature of the 20th century. . . Submitted for your approval: one Max Phillips. . .”

In the Twilight Zone, time was fluid, space wide open, and Death came in many guises — as a hitchhiker, a pool shark, even played by Robert Redford.

Along with Redford, young actors flocked to the set. Debuts included: Leonard Nimoy, Julie Newmar, Dennis Hopper, Robert Duvall, Peter Falk, Carol Burnett, and Burt Reynolds. But Serling was always the star. For the second season, he banged out 20 more scripts, then 19 the following year. Many were forgettable but some. . .

To this day, those of us who watched — and re-watched — cannot board an airplane without recalling “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” the one about the man who sees a creature chewing on the wing. We will never long for immortality without remembering “Long Live Walter Jameson,” about a man whose endless life means losing friends again and again. And then there was the one about a world heating up. . .

Each season brought another three dozen scripts. The one where William Shatner and his bride are seduced by a nickel fortune-telling machine. . . The one where Charles Bronson and Elizabeth Montgomery are the last survivors of nuclear apocalypse. . . But ratings remained weak and Serling was exhausted, “drained of ideas." After a year of hour-long episodes, and one last season, CBS canceled “The Twilight Zone.” Serling said he had “decided to cancel the network.”

Written out, he later returned to TV for three seasons of “Night Gallery.” Then, a chain smoker as tense as he seemed on camera, Serling died of a heart attack at age 50. But a dimension does not die.

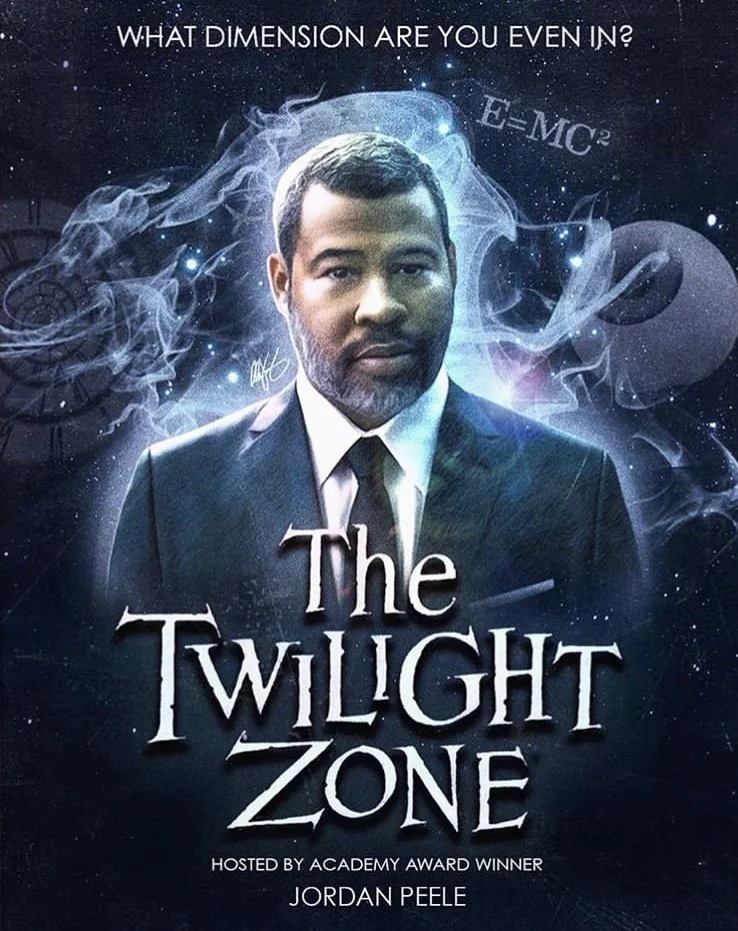

“The Twilight Zone” re-emerged in syndication, and later as a movie, several books, and three revivals with different hosts. All episodes are now available on Blu-ray and cable. The show routinely makes each All-time TV list.

Submitted, then, for your approval. A grizzled war veteran, a boxer, a scrapper wins acclaim but wearies of the fight. He steps out of the shadows. . .

“Very little comment here, save for this small aside: that the ties of flesh are deep and strong; that the capacity to love is a vital, rich, and all-consuming function of the human animal. And that you can find nobility and sacrifice and love wherever you may seek it out: down the block, in the heart, or. . . in the Twilight Zone.”