THE CYCLISTS WHO MAPPED AMERICA

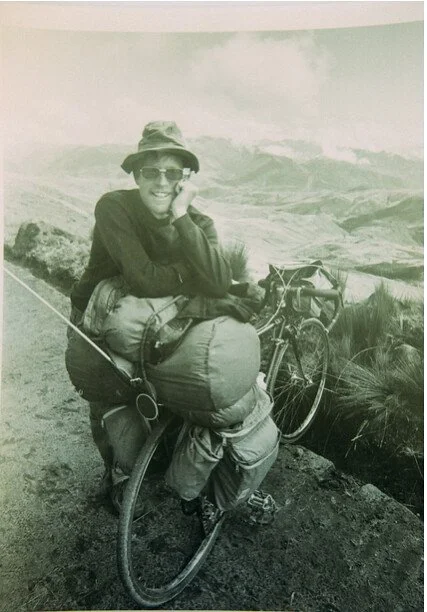

SAN FRANCISCO, DECEMBER 1972 — The roads were ugly — dirt, gravel, washboard — and the days were grueling — 70 miles or more. But having pedaled from Anchorage, Alaska to the Bay Area, Greg Siple dreamed of more.

With America’s Bicentennial approaching, why not a coast-to-coast bike ride?

“My original thought was to send out ads and flyers saying, 'Show up at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco at 9 o'clock on June 1 with your bicycle,’” Siple remembered. “I pictured a sea of people with their bikes and packs all ready to go, and there would be old men and people with balloon-tire bikes and Frenchmen who flew over just for this. Nobody would shoot a gun off or anything. At 9 o'clock everybody would just start moving. It would be like this crowd of locusts crossing America.“

Holding onto his vision, Siple, his wife June, and friends Dan and Lys Burden, hopped on their bikes and continued their own private Hemistour. Destination: Tierra del Fuego.

Back in 1884, when an Englishman first biked across America, the New York Times called him “the champion bike idiot.” In the decades since, bikes had become “kid’s toys,” Greg Siple recalled. “When you turned 16, you got a driver’s license and left the bicycle behind.”

But as they pedaled down the California coast, Siple and friends talked about their dream. Reaching Mexico, they named it — Bikecentennial. The Burdens soon went back to Ohio but the Siples cycled on, finishing their ride from Anchorage to Argentina. En route, the couples exchanged letters planning the Bikecentennial. There was much to do.

Maps. Sponsors. Safety concerns. Shelters. . .

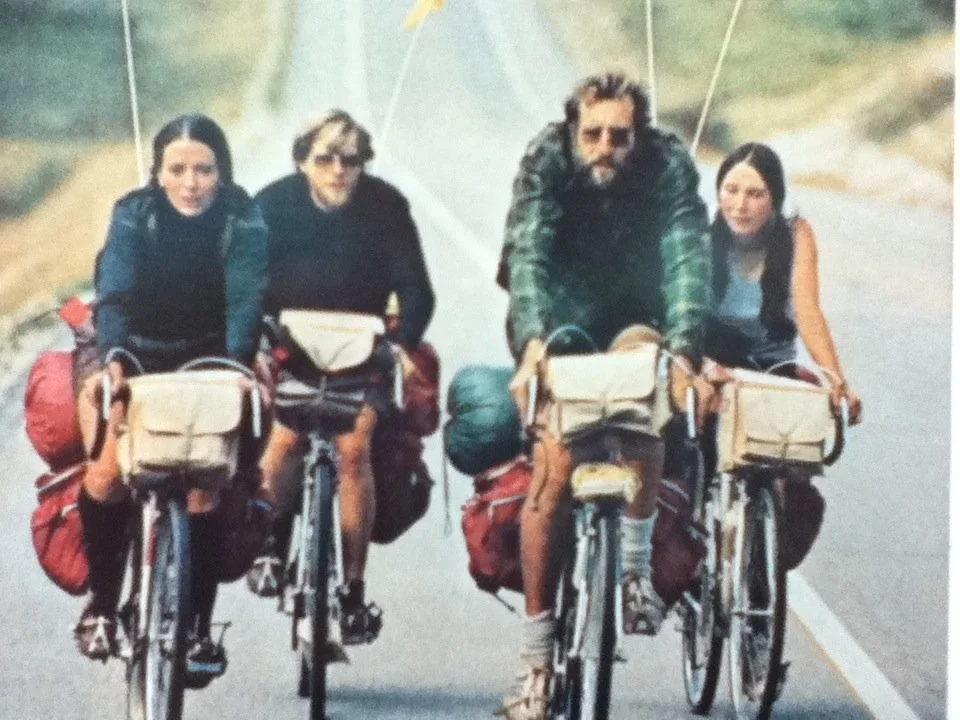

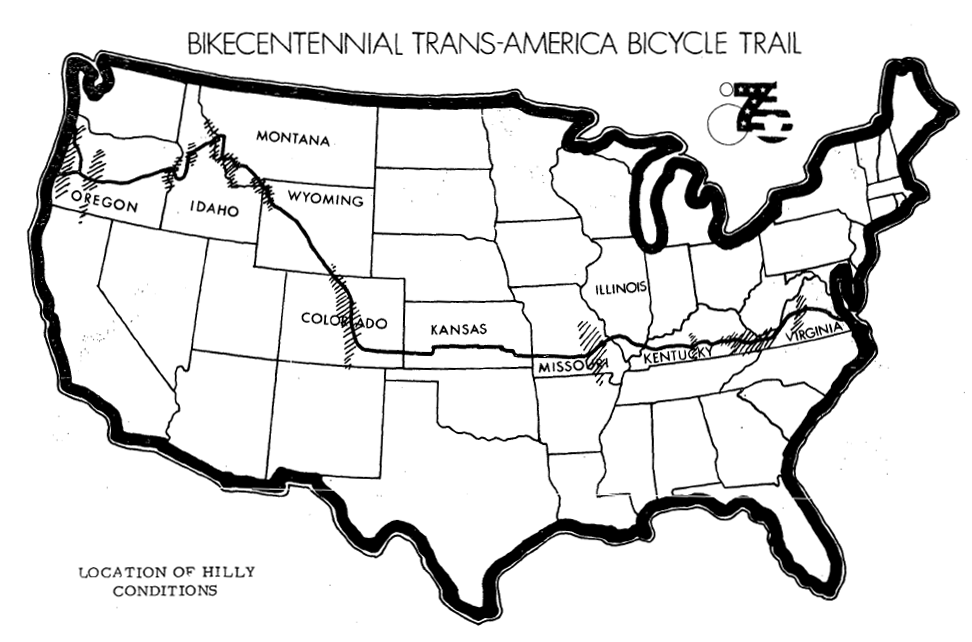

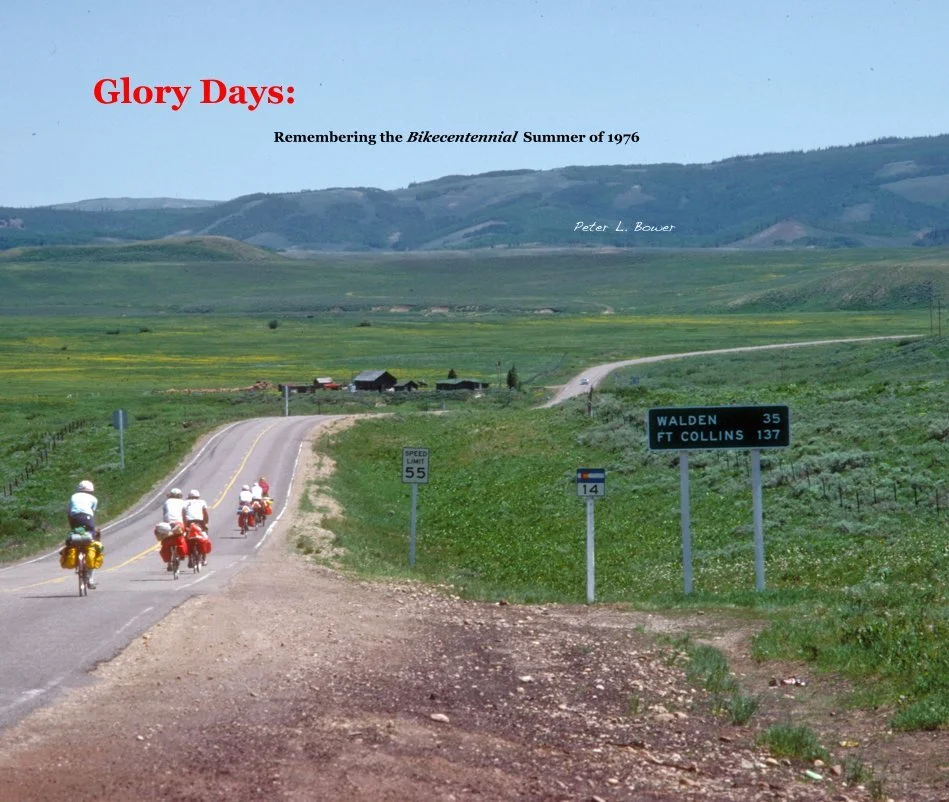

By 1975, with the Bicentennial just a year away, the Bikecentennial had a route. Time for a test-ride. That summer, two couples set out from Astoria, Oregon, across the Cascades, the Rockies, the Plains. . .

Eighty-two days, 4,200 miles. One couple reached Yorktown, Virginia without a flat tire. The other had 120 flats. But both made it! Could thousands follow?

Working out of a makeshift office in Missoula, Montana, the Siples, the Burdens, and a dozen others worked 14-hour days. Salary: $250 a month. Idealism: soaring.

“Bicycling to me somehow symbolized clean, moral living,” Charlotte Henson remembered. “I was really caught up in the whole thing. I was never going to own a car."

Having survived a 360-mile stretch of the Yukon without a single store or home, Siple and friends knew they had to plan Bikecentennnial like generals going into battle. Each day, each hazard, had to be charted, each turn in the road mapped.

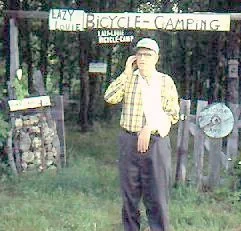

In July 1975, another couple drove the route seeking possible shelters and warning rural folks about the locusts headed their way.

"There's gonna be 10,000 people coming through here on bicycles. Can they stay in your building?"

"To many of the locals,” Stuart Crook remembered, “the idea of an adult riding a bicycle across the country was about as comprehensible as they themselves flying to the moon.”

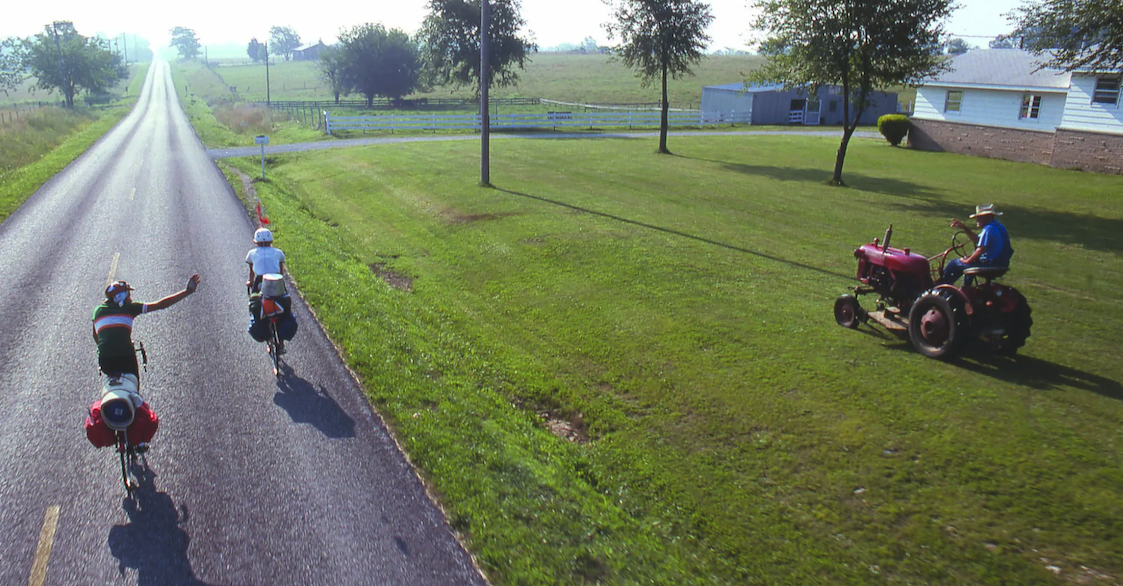

But as The Attic learned when riding/driving coast-to-coast seven summers ago (above), rural America is happy to have strangers drop by rather than fly over. The Crooks arranged stayovers on farms, in churches, schools, gymnasiums, VFW and Foreign Legion halls.

Some 10,000 fliers, sent to bike shops, recruited riders. More than 4,000, from all 50 states and 17 countries, signed up. Beyond adventure, none knew what to expect.

In May 1976, using maps made in Missoula, riding in groups of 10-12 behind a Bikecentennial guide, cyclists set out from Astoria or other trailheads. Down dirt roads, up and over passes, riding in rain, sun, frigid mornings and blistering noons, the Bikecentennial pedaled on. Surprises met them at every turn.

In Idaho, one group came down with diarrhea from campsite water. In Wyoming, in June, snow fell. Onwards.

On the Plains, near a sign reading “Welcome Bikers to Friend, Kansas,” people waved, honked, flashed their lights. In Kentucky, dogs chased bikers until “we all went after the dogs today with our ketchup bottles, fly swatters, and water bottles.”

Onwards.

A bluegrass jam on a porch in Appalachia. A “cookie lady” in Virginia, serving punch and Oreos. Down out of the mountains. Across the Piedmont. Then finally. . .

“Riding into Yorktown on the parkway, I remember sweeping around a corner and seeing just a sliver of the Atlantic Ocean. Tears welled in my eyes. We did it! Sea to shining sea!”

Two thousand-plus finished the route. A thousand more rode Golden Spokes, east- or westbound, halfway across. All came to know an America they would never forget.

“I learned more about this country in 90 days than most people learn in a lifetime."

And hometown folks gained a new respect for a generation they’d disdained as hippies or worse. “It’s young people like you that make America good,” a Missouri farmer told one rider. “We need strong people to run things after I’m dead.”

What began as a single ride grew into a network. Today, still working out of Missoula, with 50,000 members and a monthly magazine, Adventure Cycling promotes cycling for fun and the sheer hell of it. The Burdens and the Siples now peddle 30 routes covering 50,000 miles. The routes include loops, “connectors” and coast-to-coast “tiers,” the Northern (The Attic’s route), the Southern, and the 1976 route, the Trans-am.

Hundreds of Americans now ride coast-to-coast each summer. Many stop in Missoula to visit the Mecca of two-wheeled adventure. Onwards.

“Dream big,” Adventure Cycling writes. “Of your own continent crossing, or dream small of a ride out your back door to a nearby park. Either way the adventure is there, waiting to be had.”

THANKS FOR THIS STORY GO TO CLIF READ, LEADER OF THE ATTIC’S RIDE AND INTREPID VETERAN OF BOTH THE NORTHERN TIER AND THE TRANSAM ROUTE.