THAT ADORABLE GENIUS

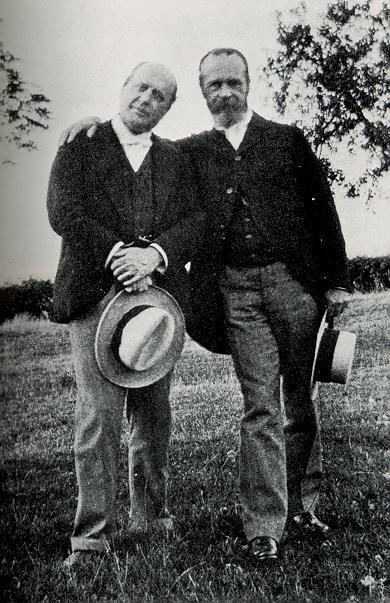

CAMBRIDGE, MA, 1880S — All over campus, students shared stories about their eccentric professor, the one in striped pants, a boater, often carrying a cane. Had he really mentioned hashish, how it slowed down time? How did he know?

Did he really attend seances? Why? What did Harvard think? Had he really rushed to a student at a stodgy gathering, grabbed him by the shoulders saying, “This place is hell! Here’s the way to escape,” and shoved him out the door?

Americans usually know William James as “Henry’s brother.” But readers bogged down in Henry James’ novels will be surprised to meet William (who also couldn’t get through his brother’s novels.)

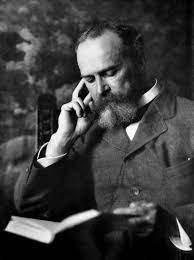

He was a man “born afresh every morning,” a man “giving off sparks.” He was “that adorable genius.” Inquisitive and amusing, troubled but triumphant, he modernized American thought in the late 19th century, first by pioneering the field of psychology, then by switching to philosophy and creating an entirely new discipline.

But beyond isms and academics, William James was simply the most open-minded American. His persistent probing of how we think led him to coin the term “stream of consciousness.” His suspicion of fame led him to denounce “the Bitch goddess, Success.” But it was his family, three geniuses under one roof, that led him to a life of ideas and wonder.

“Come,” he said to students. “Let us gossip about the universe.”

The eldest son of a zealous “seeker of truth,” William struggled to free himself from his father’s dogmatism. Across both New York and Europe, the elder Henry James dragged his five children from house to house, squelching their childhoods.

Uprooted, anxious, burdened by Father’s harangues, the James children paid what they called “the family tax.” Neuroses, stress, depression. Young Alice never got stopped paying the tax, bed-ridden by nervous breakdowns. Henry escaped to Europe where he lived all his life, writing. Two other brothers descended into alcoholism.

But William paid off his tax by buying into the future. Surviving years on the brink of suicide — should he be an artist? a doctor? a “seeker of truth?” — he surfaced by putting his faith in free will. “My first act of free will,” he declared at age 28, “shall be to believe in free will.”

“Is Life Worth Living?” he asked in a later lecture. On “this moonlit and dream-visited planet,” his answer — maybe. Despair and doubt are by-products of freedom, leaving us with Hamlet’s choice — to believe in life, or not.

“Refuse to believe, and you shall indeed be right, for you shall irretrievably perish. But believe, and again you shall be right, for you shall save yourself.” Optimism and pessimism are false choices. The only viable option lies between, in hope, in action, in living as if everything matters.

Thinking, teaching, writing, James opened his mind — wide. “He was simply keeping America’s promise,” his student Walter Lippmann remembered. ”He was actually doing what we, as a nation, proclaimed that we would do. . . He gave all men and all creeds, any idea, any theory, any superstition, a respectful hearing.”

He gave a respectful hearing to drugs. Peyote, hashish, and his favorite — nitrous oxide. They suggested a perception beyond this veil.

“Our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.”

He gave a respectful hearing to spiritualists. While Harvard colleagues scoffed, he returned to dark parlors where mediums channeled spirits. He remained mystified, wondering.

“For twenty-five years I have been in touch with the literature of psychical research, and have had acquaintance with numerous researchers. Yet I am theoretically no ‘further’ than I was at the beginning; and I confess that at times I have been tempted to believe that the Creator has eternally intended this department of nature to remain baffling, to prompt our curiosities and hopes.

Though disdainful of established churches, he gave a respectful hearing to the spiritual. His most famous book, The Varieties of Religious Experience, Is a highly readable account of spiritual encounters throughout history.

“There are moments of sentimental and mystical experience. . . that carry an enormous sense of inner authority and illumination with them when they come. But they come seldom, and they do not come to everyone.”

Varieties led to lectures on Pragmatism, the very American philosophy of testing ideas by how well they work.

“Truth is made, just as health, wealth and strength are made, in the course of experience. . . Truth grafts itself on previous truth, modifying it in the process, just as idiom grafts itself on previous idiom, and law on previous law.”

When he died in 1910, mediums claimed to contact his spirit. Others were content to remember “that adorable genius” by the ideas he left us. “Stream of consciousness” soon changed literature. Pragmatism dominated American philosophy for decades. And his “maybe,” the idea that we must battle despair with possibility, endures.

“If this life be not a real fight in which something is eternally gained for the universe by success, it is no better than a game of private theatricals. . . But it feels like a real fight — as if there were something really wild in the universe which we, with all our idealities and faithfulness, are needed to redeem.”