ART BY POPULAR DEMAND

THE ART WORLD — 1994 — The old cliche refuses to die. “I don’t know anything about art but I know what I like.” Really? You’re sure about that? Because to cite another cliche, “be careful what you wish for.”

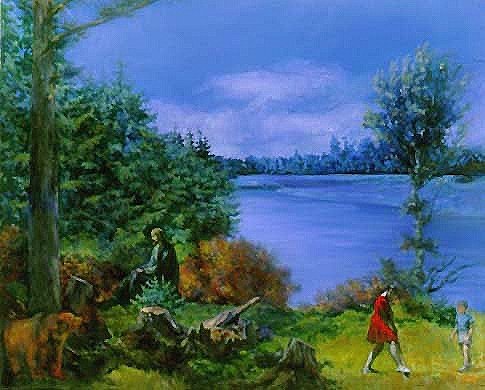

Look. Here is “America’s Most Wanted” painting.

Note the lovely lake where the deer and hippo play. And who could miss, front and center, George Washington himself? This is America’s Most Wanted? This?

“What is striking about America’s Most Wanted,” wrote critic Arthur C. Danto, “is that I cannot imagine anyone really wanting it as a painting.”

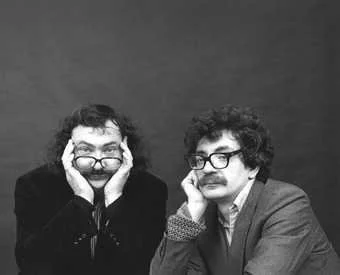

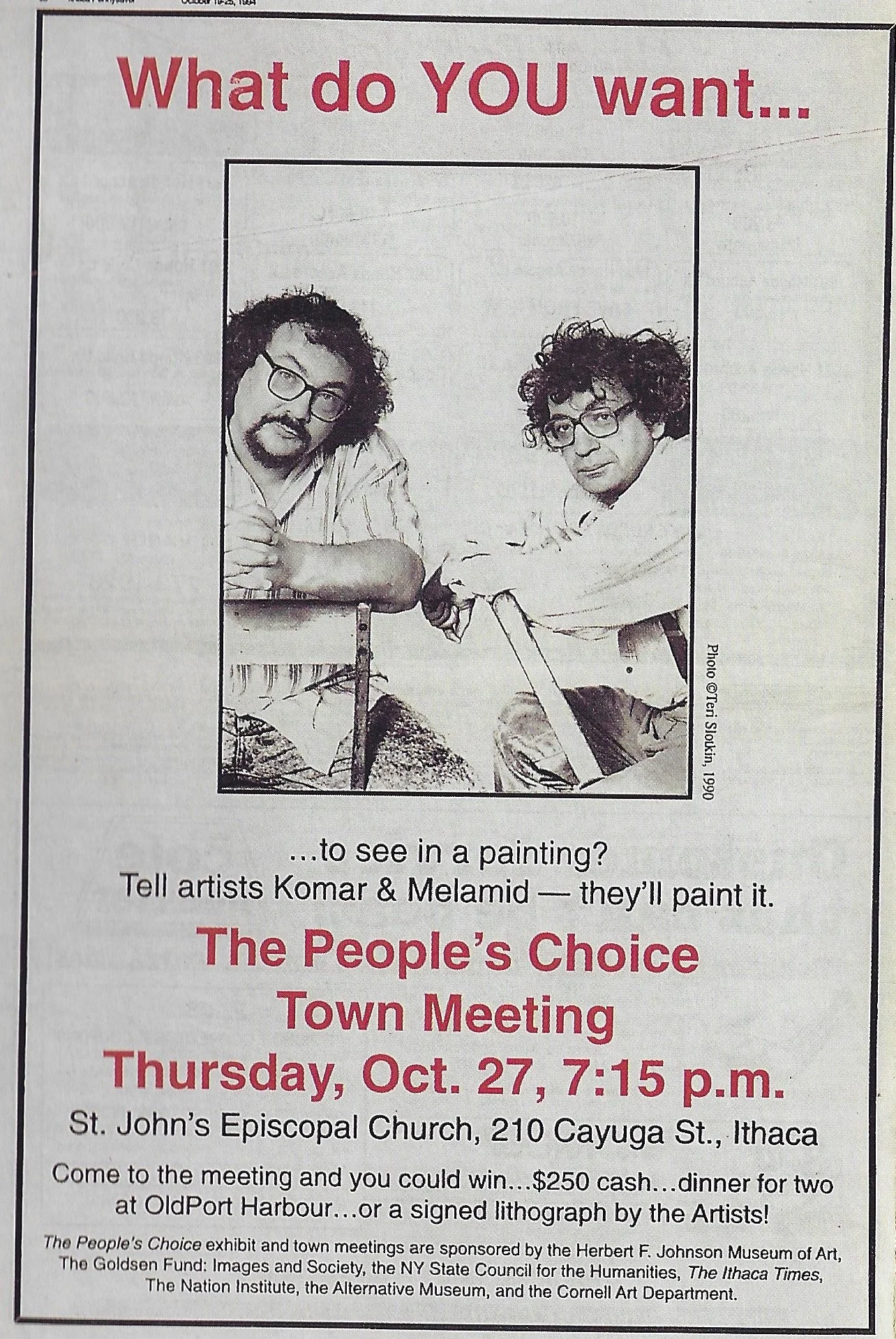

But back in the mid-90s, Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid did polling, held town meetings, and painted precisely what “the people” wanted. Their “People’s Choice Project” was seen as “funny, prickly, complex, humane, dense with implications and a baited trap for ideologues and hypocrites.”

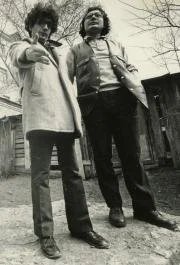

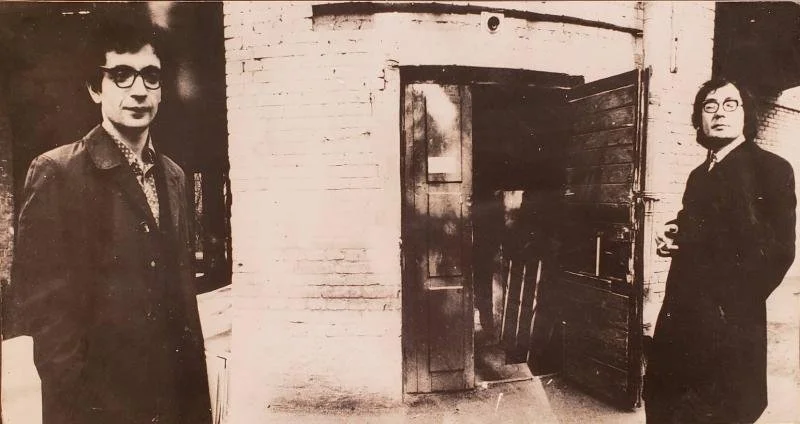

Before polling, Komar and Melamid spent decades balancing irony and reverence. Born in Stalin’s Soviet Union, the two met in a Moscow art academy in the mid-1960s. Sharing a sense of humor and a love of Andy Warhol, they soon teamed up to shock the Soviet art world.

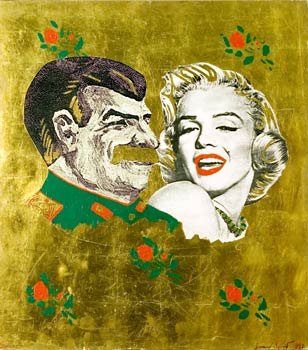

Socialist realism was the Kremlin’s official art. Komar and Melamid obliged, creating bold, heroic portraits of workers and Soviet icons. Then they pushed back.

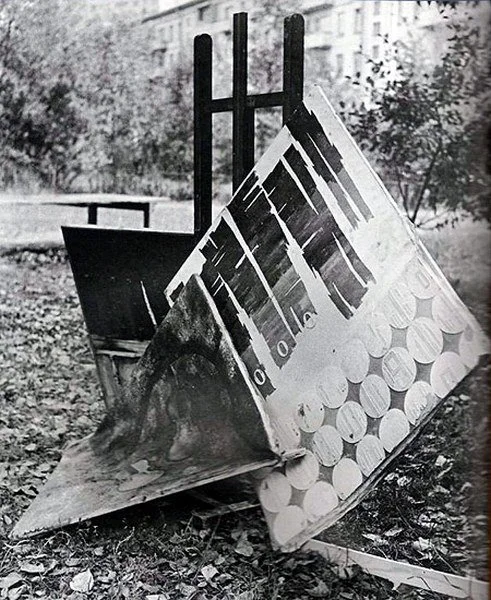

Here was Lenin — hawking Coca-Cola. Here was Stalin, with Marilyn Monroe. Their “Sots Art,” blending Soviet Pop with conceptual art, made Komar and Melamid art refuseniks. Ejected from the Soviet Artist Union, they joined fellow rebels for “The Bulldozer Exhibition,” so-named after Soviet police tore up the show and smashed every work. In the melee, Komar was knocked sprawling. Melamid was told, “You should be shot only you are not worth the ammunition.”

Struggling to emigrate, the duo moved to Israel in 1977. The following year, they landed in New York. By the mid-1980s, their works were shown in major American museums.

Newly nationalized American citizens, they struggled to comprehend this curious country where everyone has opinions about art but few buy any. Near their New Jersey studio, just one store sold paintings, “really inferior, terrible art,” Melamid said. “And people buy these terrible pictures, but do they like them? Or is it just all they have? Maybe if we ask them they will give the answer.”

In December 1993, the polling began. Hired by Komar and Melamid, a Boston-based firm sampled 1,001 Americans across all demographics. Patient people answered 102 questions.

— What is your favorite color? (Blue, 44%).

— Do you prefer outdoor or indoor scenes? (Outdoor 88%)

— Realistic or abstract (Realistic 60%)

— Modern or traditional art (Traditional 64%)

— Sharp angles or soft curves? (Curves 62%)

Komar and Melamid held town meetings in Ithaca, New York, listening as people described their dreamscapes.

“A nice realistic picture of a nice old hillside farm. . . A small grouping of trees and sitting on a picnic blanket. . . A painting which represents the four seasons. . .”

Armed with data and wishlists, the pair returned to New Jersey to paint. In 1994, America’s Most Wanted opened at the Alternative Museum in Manhattan. Roaming the gallery, people sipped blue vodka, sniffed and snooted.

“I think that talking about what the people want is absurd,” one art historian said. Others criticized Komar and Melamid for pandering to public opinion. “This painting is so dull, so predictable,” one said. “It’s like something you could buy at Kmart.”

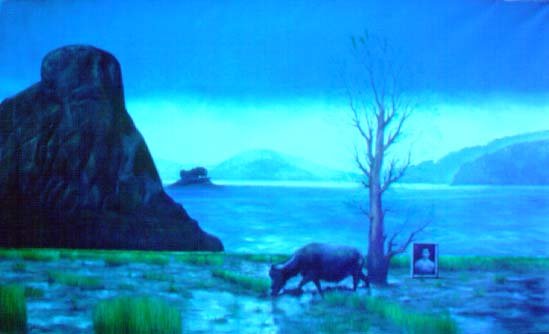

Yet it was not so easy to dismiss the project, especially when the Dia Art Center backed its expansion with polling in 14 other countries, from (above) Russia to Kenya to Denmark to China. By 1998, Komar and Melamid had the “most wanted” paintings for each.

"Our interpretation of polls is our collaboration with various people of the world,” Komar said. “It is a collaboration with new dictator — Majority."

Tongues in cheeks, Komar and Melamid had probed the gap between what the art public wanted and what it received. And their “Least Wanted” paintings (Italy’s above, America’s below) only broadened that gap.

Beyond the canvas, the duo’s data offered insights into imagination and dreams. Why did every country, every demographic favor the same color — blue?

“Almost everyone you talk to directly — and we’ve already talked to hundreds of people — they have this blue landscape in their head,” Melamid said. “It sits there and it’s not a joke. They can see it, down to smallest detail. So I’m wondering, maybe the blue landscape is genetically imprinted in us, that it’s the paradise within, that we came from the blue landscape and we want it.”

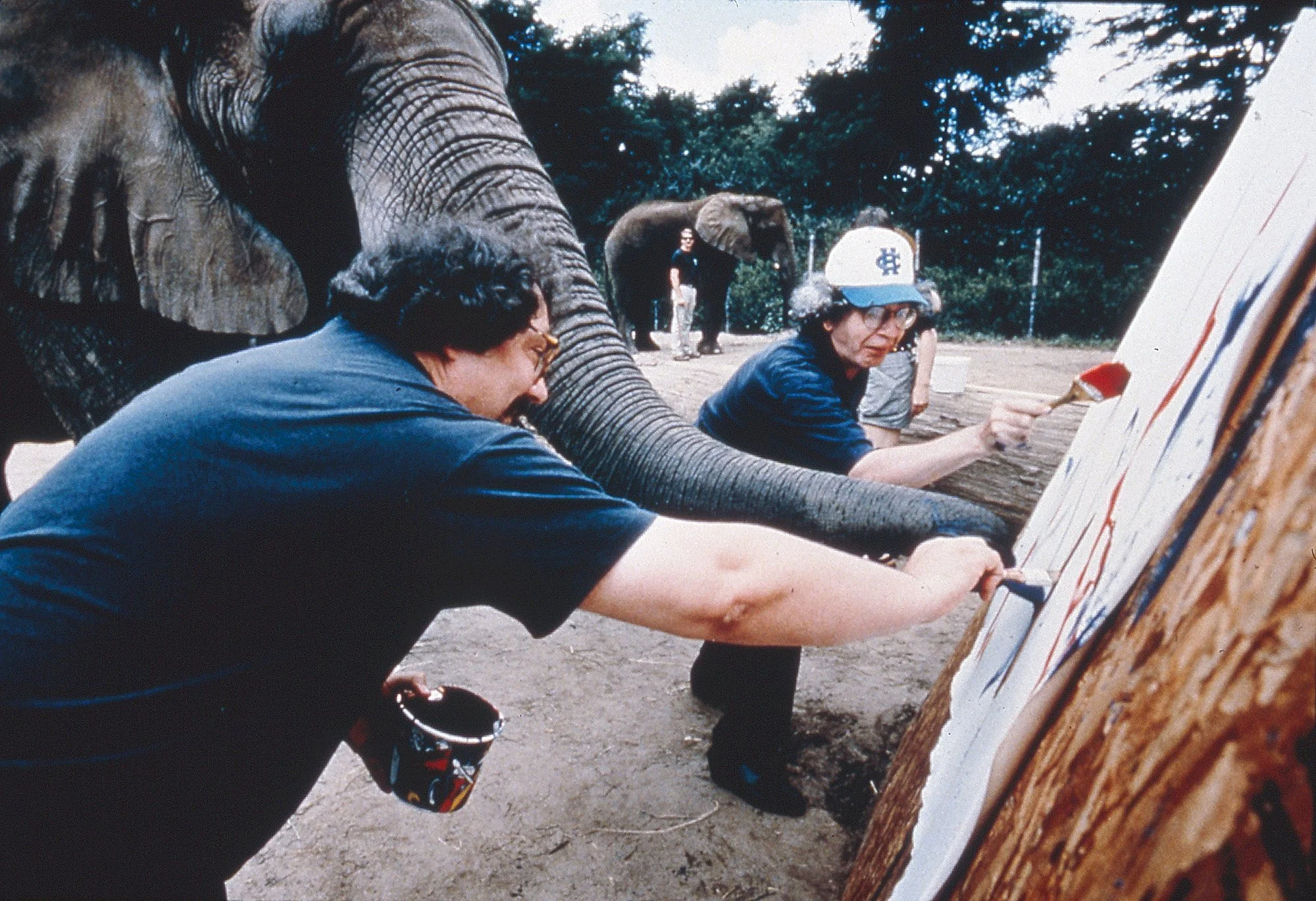

After five years of polling and painting, Komar and Melamid moved on. They taught elephants to paint. They composed an opera featuring Washington, Lenin, and Marcel Duchamp. Then in 2003, they went separate ways.

Komar and Melamid continue to paint on their own. Komar’s favorite themes are 9/11, COVID-19, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Melamid prefers painting rap artists as depicted by the Old Masters.

But contrasting their communist roots with their capitalist home, both remain fascinated by “the people” and their taste in art.

“Vitaly and I were brought up with the idea that art belongs to the people,” Melamid said. “And believe it or not, I still believe this. I truly believe that the people’s art is better than aristocratic art, whatever it is.”