THE OTHER WASHINGTON MONUMENT

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES — September 1908 — Bored by another speech, the president’s daughter sits in the gallery’s front row. She is considering walking out when she spots a tack on the floor. She slips out of her seat and puts the tack on the seat of a Congressman. A calling card from Alice.

Born during America’s Gilded Age, she lived to the age of Reagan. Through 19 presidents, scores of Congresses, and a litany of war and scandal and gossip, she was more than just a president’s daughter, more than the wife of the Speaker of the House.

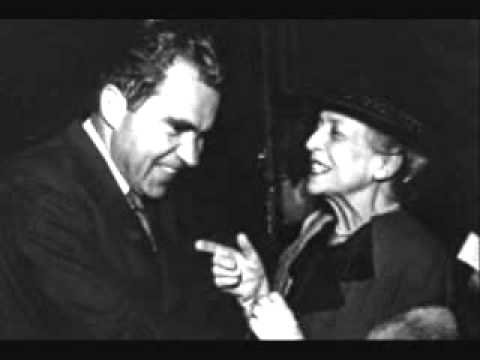

Sassy, witty, sometimes mean but always in the news, Alice Roosevelt Longworth was one of the most influential women in the nation’s capital. In her 80s, when she was dubbed “the other Washington monument,” Richard Nixon summed up her allure. “She was the most interesting conversationalist of the age. No one, no matter how famous, could ever outshine her.”

Yet Alice preferred wit to wisdom. Her take on D.C. society was the phrase she embroidered on a pillow. “If you haven't got anything nice to say about anybody, come sit next to me."

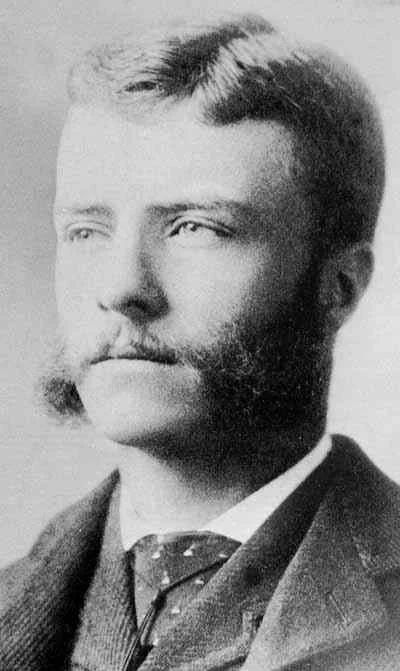

But if brevity is the soul of wit, then sorrow is its heart. Alice was only two days old when tragedy struck. First her grandmother died of typhoid fever. Eleven hours later, her mother died of kidney failure. Having lost wife and mother, Theodore Roosevelt wrote, “The light has gone out of my life.”

To recover, Roosevelt expunged his wife from memory. He never spoke about her again, nor allowed anyone else to utter her name. He soon left New York for the Dakotas to ranch, ride, and outlast his grief. He left Alice, called “Baby Lee” with his sister.

Anna Roosevelt raised Alice for two years, until her father came home and re-married. “If Auntie Bay had been a man,” Alice later wrote, “she would have been president.”

Feeling an outsider as her father and step-mother added five children to the family, Alice rebelled at every chance. Threatened with boarding school, she said, “If you send me I will humiliate you. I will do something that will shame you. I tell you I will.”

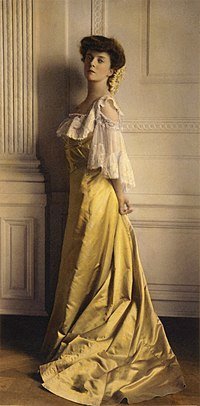

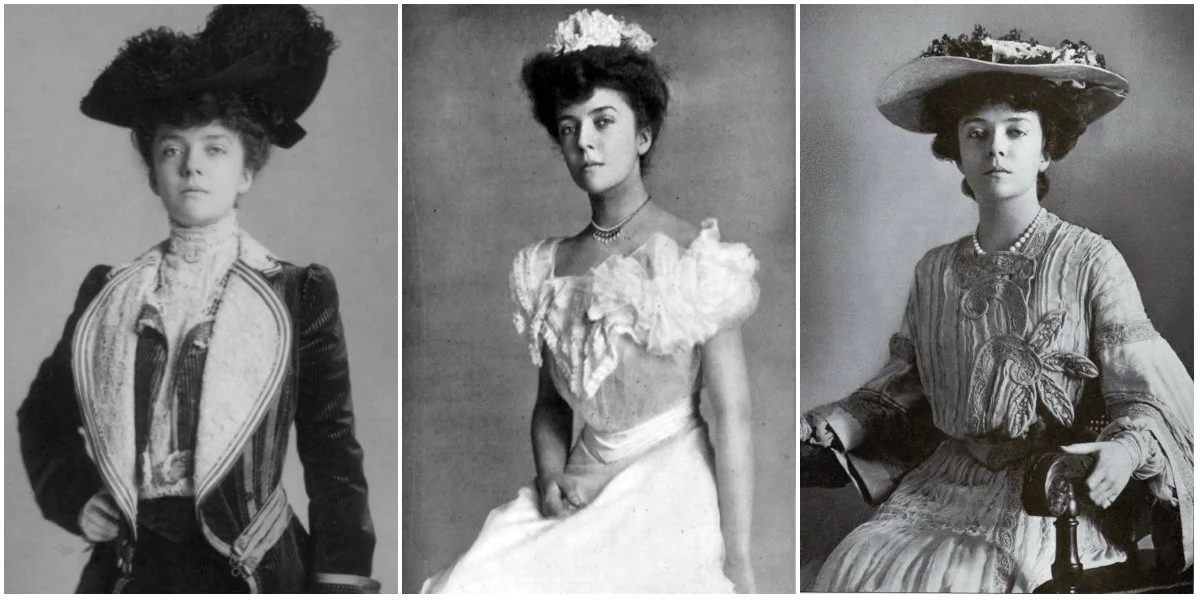

Then in 1901, an assassination turned vice-president Roosevelt into the youngest president ever. His teenage daughter was in “sheer rapture.” Alice was soon the talk of D.C. Her gown spawned a craze for “Alice blue.” She attended hundreds of balls, dances, society events.

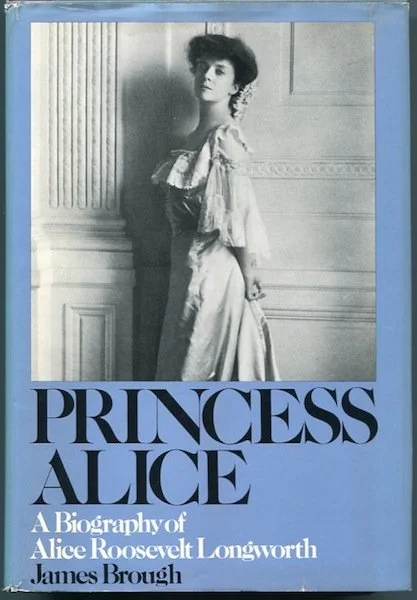

The press loved “Princess Alice.” She placed bets with a bookie, smoked in public, kept a pet snake named Emily Spinach. During a diplomatic tour of Japan, she jumped into a pool with her clothes on.

"I can either run the country or I can attend to Alice,” her father told a friend. “I cannot possibly do both."

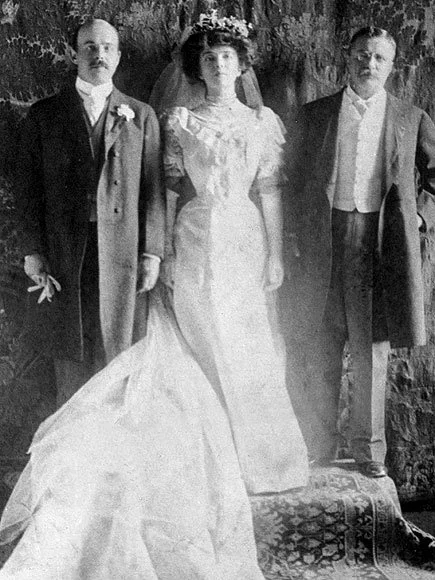

In 1906, Alice’s wedding to a young Congressman was the social event of the year. Worried her father might upstage her, Alice grabbed a guard’s sword and wielded it to cut the cake.

But the marriage soon soured. When her husband, Nicholas Longworth, began having affairs, Alice answered with her own.

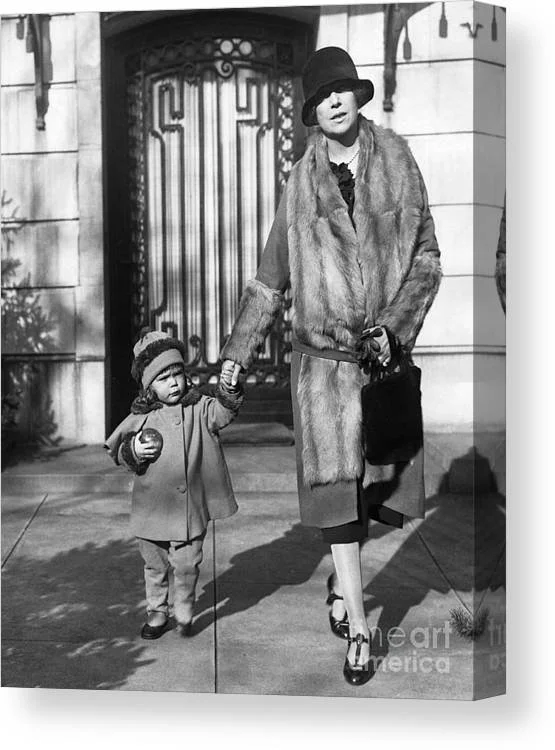

Alice’s long affair with Congressman William Borah was a secret all over D.C. When she bore his child, whispers called the girl Aurora Borah Alice. Alice wanted to call her Deborah, from “de Borah.” She settled for Paulina.

On through the Twenties, Alice held court from the Longworth home. She played poker and went to boxing matches. And in the blood sport of politics, D.C. welcomed her wit, wielded against president after president.

President Coolidge — “He looks like he was weaned on a pickle.”

Her cousin, FDR — “Two-thirds mush and one-third Eleanor.”

And her egocentric father — “He wants to be the bride at every wedding, the corpse at every funeral, and the baby at every christening."

During the Depression, a British journalist visiting D.C. noted, “intellectually, spiritually, the city is dominated by the last good thing said by Alice Longworth.” But behind Alice’s wit was a savvy political acumen.

“Alice Longworth never made a speech in her life and never gave an interview,” the New Yorker wrote. “Yet in her imperceptible way she is one of the most influential women in Washington. She knows men, measure, and motives; has an understanding grasp of their changes.”

Alice’s notoriety survived her husband’s death in 1931. And Alice survived breast cancer, political infighting, and feud after feud. Though a lifelong Republican, she was revered by both parties. Jimmy Carter later wondered which was worse, “to be skewered by her wit or to be ignored by her."

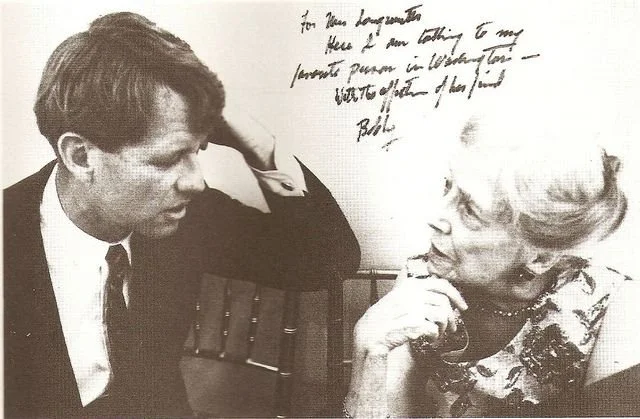

From JFK, she “learned how amusing and attractive Democrats could be." She voted for LBJ and backed her good friend Bobby Kennedy for president in ‘68. But. . .

At 82, she donned a mask and hobnobbed with celebrities at Truman Capote’s “Black and White Ball.” Later she survived a second mastectomy. Though few talked about breast cancer back then, Alice proclaimed herself “Washington’s Only Topless Octogenarian.”

Through the 1970s, this child of the Gilded Age soldiered on. But eight days after turning 96, Alice died in her D.C. home. Her granddaughter sat by her, hoping for some final, witty words. There were none. Still Alice to the end, “the other Washington monument” simply stuck out her tongue.

Today, when politics is less a blood sport than a middle school shouting match, D.C. could use a little wit. But there was only one Alice..

“I have a simple philosophy,” she often said. “Fill what’s empty. Empty what’s full. Scratch where it itches.”