CITRUS COOL

ORANGE COUNTY, CA — 1877 — From snowcapped mountains to Pacific shores, Southern California was open and empty. Just a quarter million people lived there. The weather was warm year round, but dry, dry, dry. The Gold Rush that grew San Francisco was over, leaving hard times. And this semi-desert “Southland” seemed destined to remain a distant outpost, an “island on the land.”

Then one summer day, the new Southern Pacific rolled east with a load of freight. One car carried a rare fruit, a delicacy usually saved for Christmas.

Packed in wooden crates, the precious cargo was bound for St. Louis, the farthest the fruit could survive without refrigeration. Each crate had a label — WOLFSKILL CALIFORNIA ORANGES.

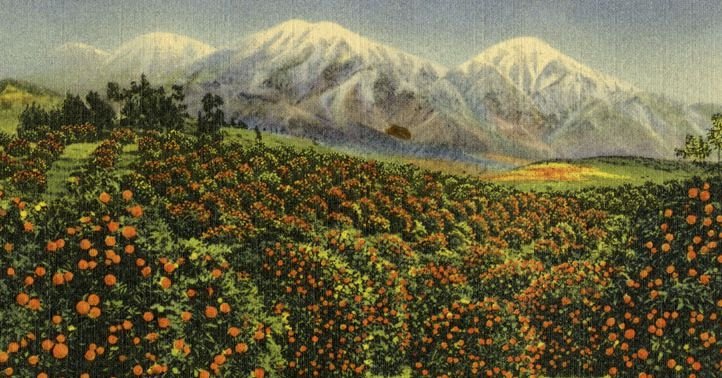

The orange, wrote one L.A. pioneer, is “not only a fruit but a romance.” Symbols of sunshine, oranges have moved beyond holiday treat to become part of America’s daily diet. Yet that change required more than refrigeration. It required art.

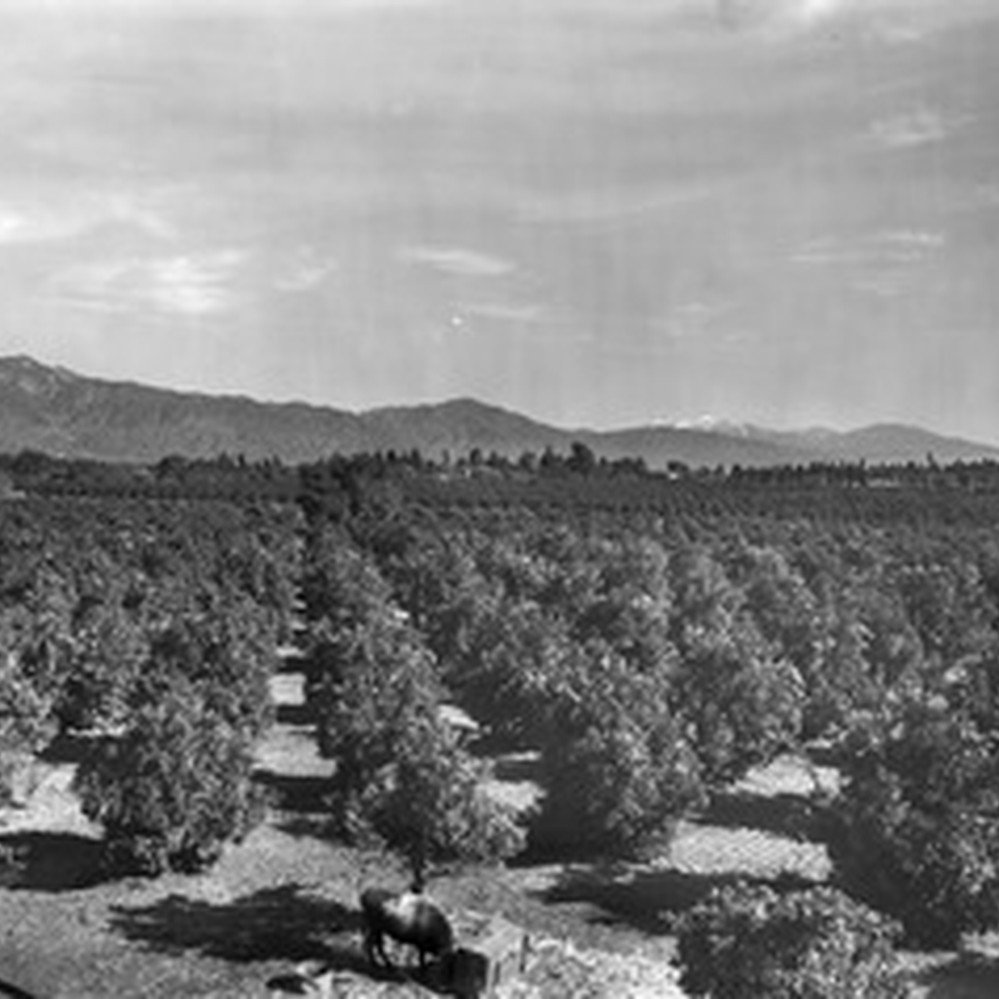

By 1900, Orange County was “one vast orchard dotted with little towns.” The Citrus Belt, stretching from Riverside to the San Fernando Valley, hosted five million orange trees. “The gold nuggets of Southern California” were sold coast-to-coast. And because one orange was pretty much like any other, the labels on each crate sold far more than fruit. As L.A.’s unofficial bard, Brian Wilson, sang:

Orange crate art was a place to start

Orange crate art was a world apart.

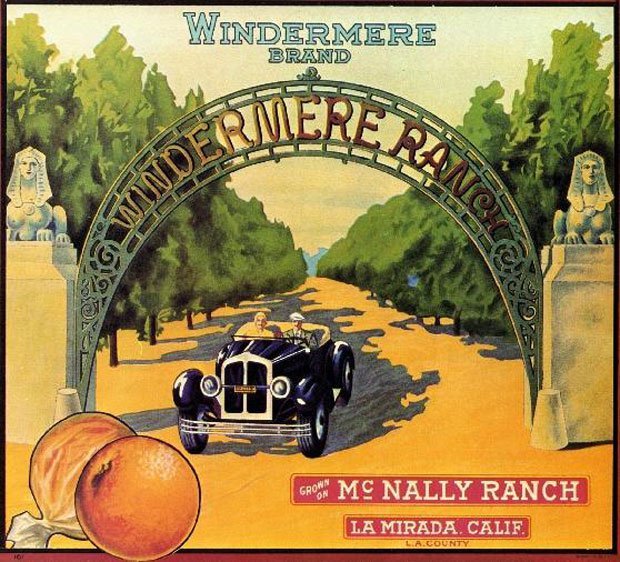

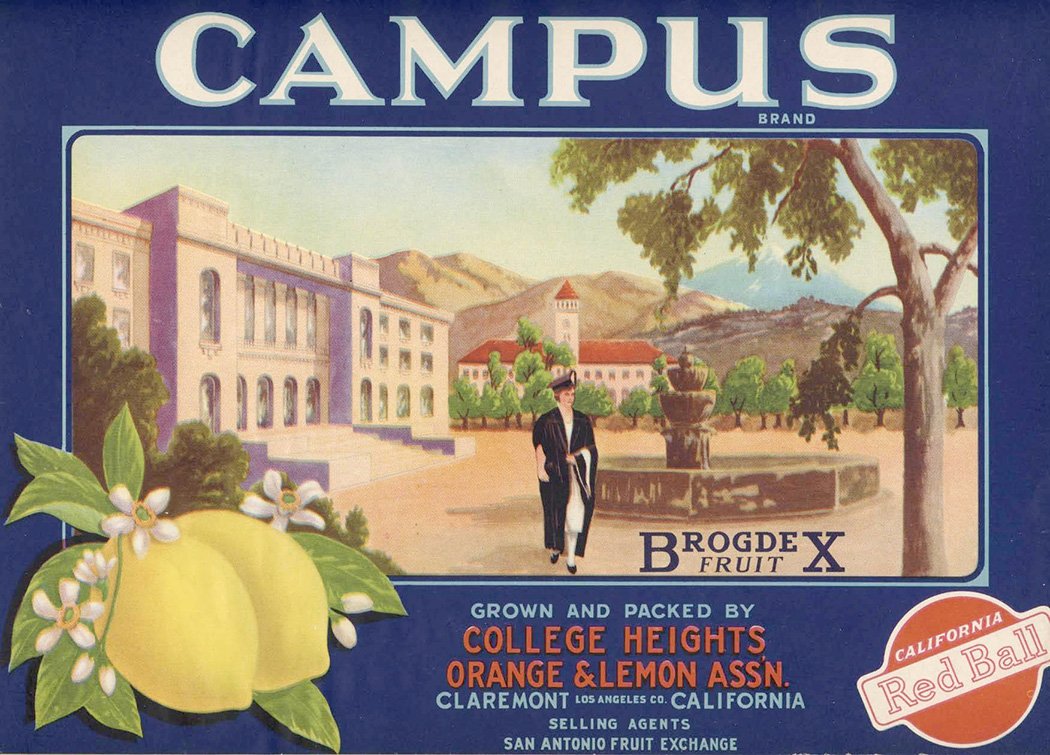

The world apart blossomed in the early years of the boom. By 1890, printers in San Francisco, struggling since the Gold Rush, were happy to mine this new market for labels. Some printers sent artists south, into the groves, where they personalized labels with sketches of local buildings or a grower’s wife. Growers called such artists “scissormen,” and they knew a gold mine when they saw one.

By 1915, Orange and L.A. counties were the richest agricultural counties in America. “To own an orange grove in Southern California,” historian Carey McWilliams wrote, “is to live on the real gold coast of American agriculture.”

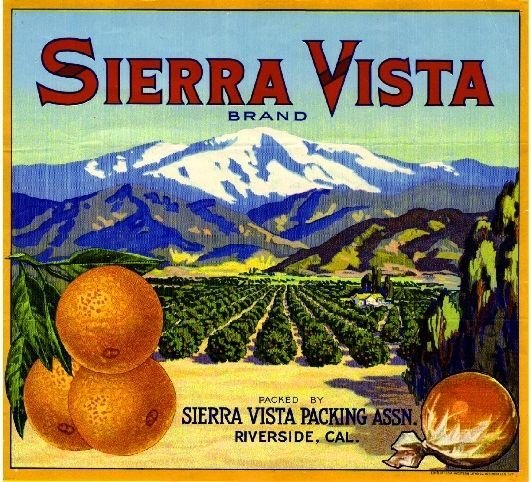

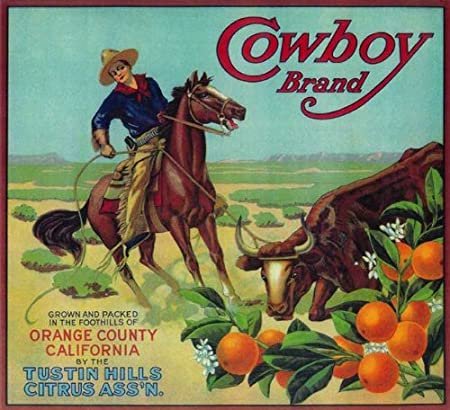

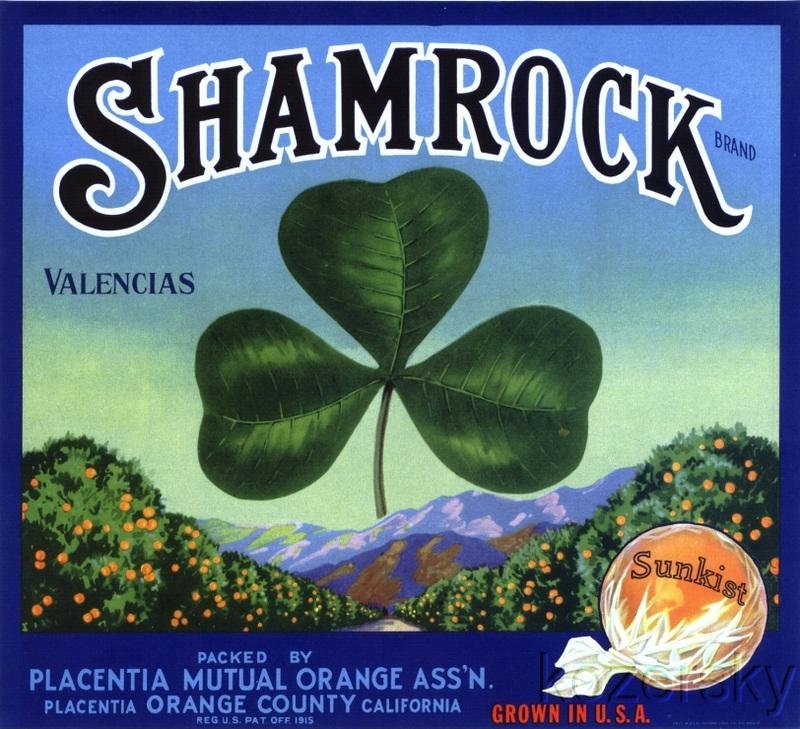

Along with income, orange crate labels were an artist’s dream. Two for every crate, they demanded bright colors, Pacific blues and citrus hues deepened by printing on limestone blocks with metallic inks and varnishes. And they tapped American mythology.

The motifs were as eternal as all myths about the American West. Open fields, gorgeous mountains, cowboys, women, and perpetual summer. Each crate of oranges, labels suggested, contained California itself. Even growers who did not belabor the cliche of “golden” — Golden Sceptre, Golden Buckle, Golden Treat, Golden Cross — wanted labels that sold sunshine, summer, and success.

“Most markets and grocery stores displayed produce in the same wooden crates in which it was delivered,” Collectors Weekly wrote, “so colorful labels became a great way for growers to differentiate their products from competitors and catch a shopper's eye.”

By 1940, some 10,000 different labels had done their job. That year, Southern California shipped 65,000 freight cars packed with oranges. Yet along with selling the myth, labels hid harsh truths.

Fifteen thousand migrant workers, first from China, then Japan, later from Mexico, lived in shacks beside the groves, earning pennies for each bushel picked. When they occasionally went on strike, they were beaten or tear gassed. Don’t even talk union.

But along with labor troubles, oranges faced a mightier force — sprawl. In 1953, cartoonist Walt Disney bought 160 acres of groves in Anaheim. Two years later, as the orange industry replaced crates with pre-printed cardboard boxes, Disney turned his orange acreage into Disneyland.

Though originally an island in the groves, Disneyland soon spearheaded a massive influx of families, freeways, and housing tracts. The Citrus Belt doubled in population, then doubled again. And again. By 1970, if you wanted to pick an orange, you had to go to the far fringes of Southern California, or else to Florida.

The orange groves have been plowed under, paved over, but the labels are a growing business online. Search Ebay, Etsy, Amazon. Orange crate nostalgia calls to the collector, the dreamer, the hometown kids (like me) who remember running through the groves. Prints sell for $10 - $80. Originals go for hundreds each. California libraries host label collections numbering in the thousands.

More than just “a place to start,” orange crate art remains unique in American commercial history. No one collects labels for peas or carrots. Something about the times, the paradise lost, and the “gold nugget” itself make orange crate art, as Brian Wilson crooned — “a world apart.”

Home for two with a view of Sonoma

Where there’s aroma and heart

Memories of her orange crate art.