MOTHER JONES AND THE CHILDREN'S CRUSADE

PHILADELPHIA, SUMMER 1903 — Another Fourth looms. There will be parades, fireworks, and this year the Liberty Bell touring America on a train car. But in Independence Park, a different kind of patriotism is brewing.

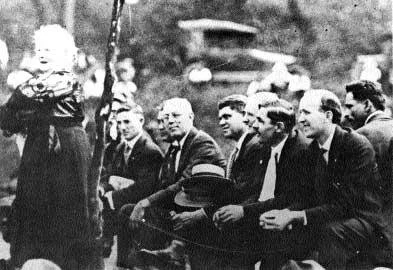

A white-haired woman in a black dress stands at a podium. She calls a few children to join her. They scramble up steps and face the crowd. But are these children? All are worn down, a pack of defeated waifs “from whom all the childhood had gone.” At the woman’s request, some hold up hands to show missing fingers, mangled limbs.

Philadelphia’s mansions, the woman says, are built on “the broken bones, the quivering hearts, and drooping heads of these children.” When hoots come from the adjacent City Hall, the woman shouts, “Someday the workers will take possession of your city hall and when we do, no child will be sacrificed on the altar of profit!”

By 1903, Mary Harris Jones was notorious nationwide. Though a saint to some, she insisted, “I am not a humanitarian, I am a hell-raiser.” Just months had passed since, on trial in West Virginia for breaking a strike injunction, her prosecutor told the jury, “There sits the most dangerous woman in America.“

Dangerous? A little old lady in black? America was about learn why, but it would be decades before they learned of the sorrow that made “Mother” Jones.

Born in Ireland, she was eleven when the Great Famine sent her family to Canada. After schooling in Toronto, she taught in Michigan, then moved to Memphis where she met and married iron worker George Jones.

A woman’s place is in the home, this “radical” always claimed, and Mary Jones left teaching to raise four children. Then in 1867, yellow fever swept through Memphis. Her husband fell first, then all four children, one-by-one. Distraught, Jones moved to Chicago and started a dress business. Then came the Great Fire.

The coming decades might have been blurred by tears, but Jones followed the advice of Joe Hill, whose I.W.W. she helped jumpstart. “Don’t mourn; organize.”

In 1897, at age 60, she began calling herself “Mother” Jones. By then, she had spoken and marched in mining and mill towns across a brawny America.

“Mother Jones,” a friend wrote, “is above and beyond all, one of the working class. She is flesh of their flesh, blood of their blood. Wherever she goes she enters into the lives of the toilers and becomes part of them. She is indeed their mother in word and deed.”

Then in 1903, she found a new cause.

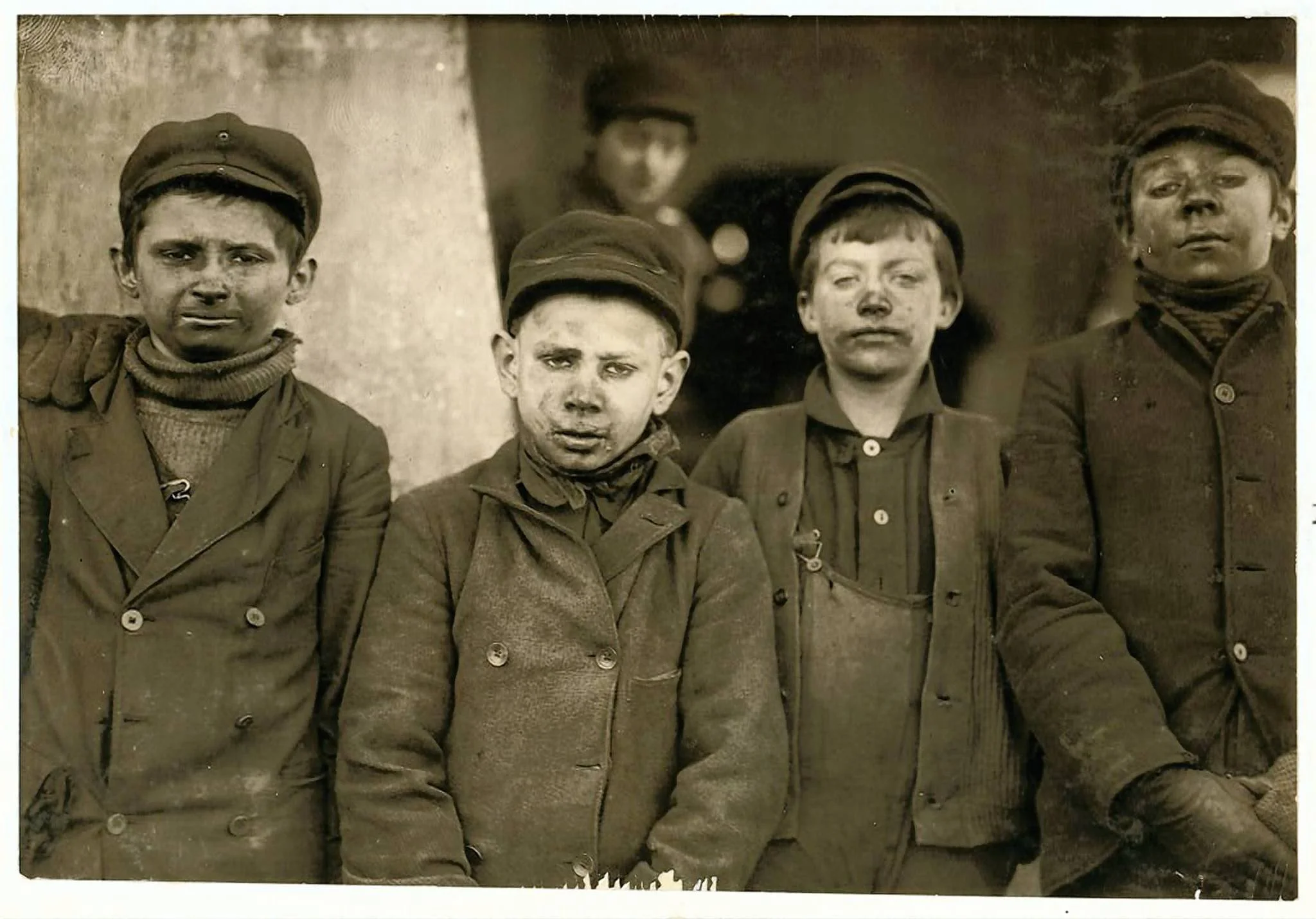

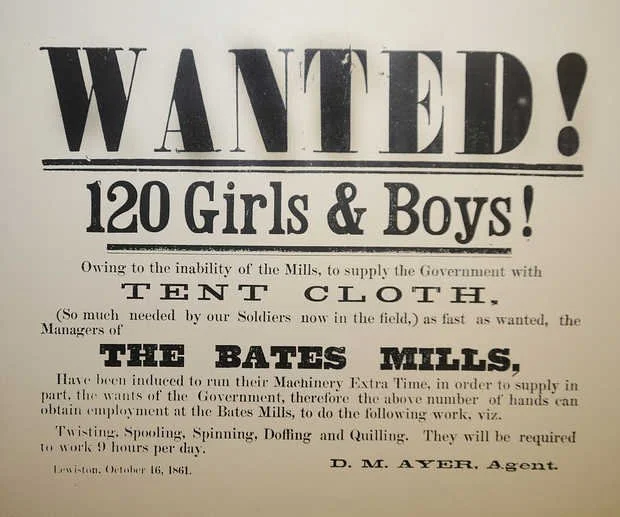

She had seen them in every mine and mill. Boys, just boys, picking rocks from coal bins, girls, mere girls, feeding thread into looms. With no federal child labor law, and the few state laws widely ignored, some two million children, 14 and under, toiled twelve-hour days.

“I wondered that armies did not stand forth to free those slaves,” she wrote. In Philadelphia, Jones learned, newspapers never mentioned child labor. Seems the mill owners held newspaper stock.

"Well, I've got stock in these little children,” she said, “and I'll arrange a little publicity." If the Liberty Bell could tour America, so could child labor.

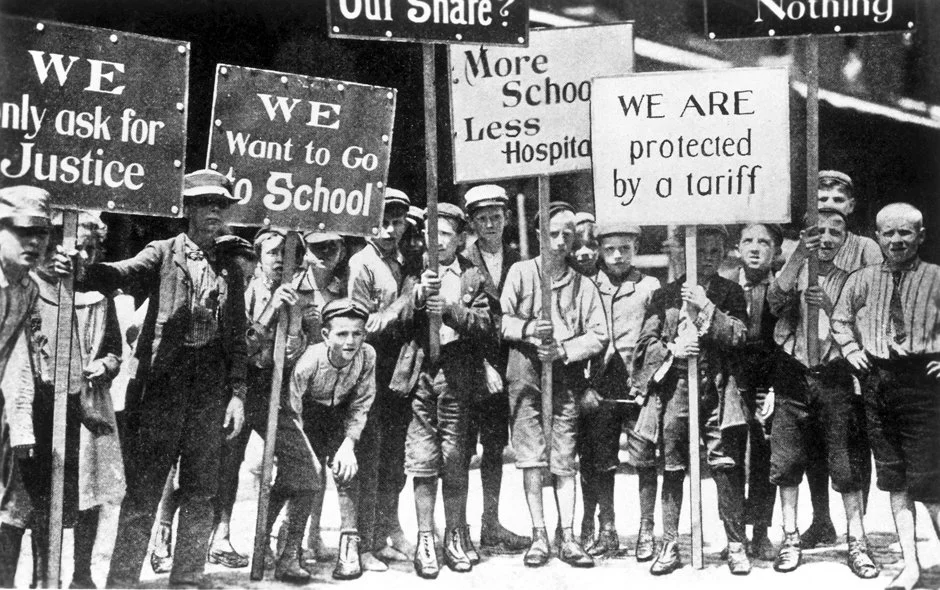

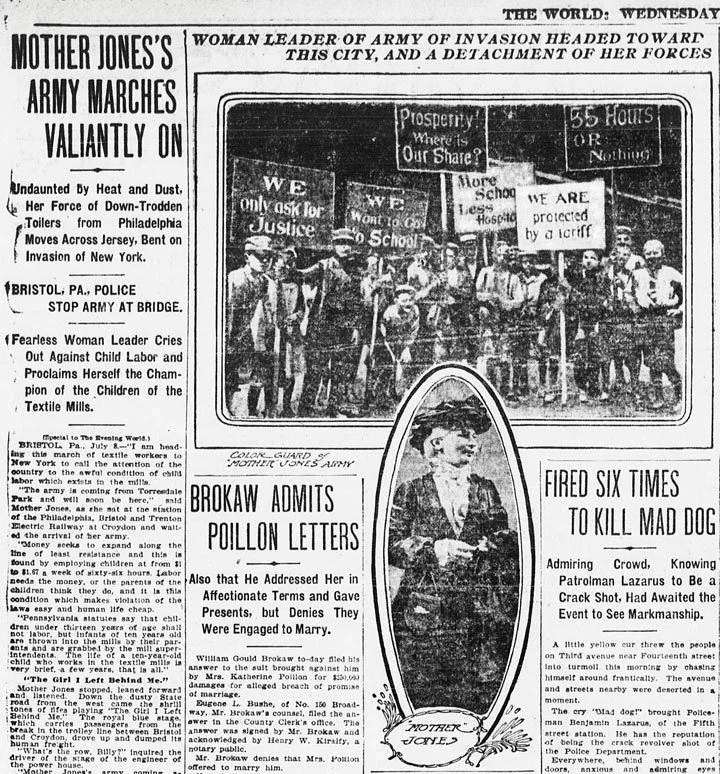

A few days after the Fourth, 100 children, with chaperones and a marshal, marched out of Philadelphia bound for Wall Street. “I am going to show Wall Street the flesh and blood from which it squeezes its wealth.”

Across New Jersey, behind banners, fife, and drum, the “march of the mill children” made headlines. Cops in Trenton tried to divert the march, but when children entered the city, policemen’s wives fed and housed them. In Princeton, Jones offered professors and students an economics lesson.

“Here's a textbook on economics,” she said, pointing to one boy. “He gets three dollars a week and his sister who is fourteen gets six dollars. They work in a carpet factory ten hours a day while the children of the rich are getting their higher education."

For two weeks and 100 miles, the march shone a harsh light on child labor. Most of the press mocked the “band of lunatics,” but people paid attention, especially when Jones rerouted the march to Sagamore Hill, home of President Theodore Roosevelt.

Speaking at Coney Island, where the children rode Ferris wheels and splashed in the surf, Mother Jones told a crowd, “I shall ask the president in the name of the aching hearts of these little ones that he emancipate them from slavery.” But Roosevelt refused to see Mother Jones, even when she downsized her march, taking just a few children to his home. By August, Child Labor was back at work.

But “the children’s crusade,” a mining journal wrote, “helped to give child labor a mortal stab. And though it will take plenty of time to kill the cruel monster than insists on feeling off the flesh and blood of little children, yet it is doomed.”

Mother Jones organized on into her eighties. When she died in 1930, there was still no federal child labor law — two were struck down by the Supreme Court — and there would no lasting laws until the New Deal.

By then, a singular gravestone stood on the Illinois prairie, a tall obelisk flanked by statues of miners. At its dedication in 1936, 50,000 paid their respects to “the miner’s angel.” Many had met her, others only heard stories, yet all knew her signature statement:

“Pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.”