THE MAINE GIRL AND THE SOVIET PREMIERE

THE COLD WAR, NOVEMBER 1982 — The coldest winter loomed. Over protests across Europe, new missiles, Soviet and American, brought the world to the brink. With arms talks stalled, 50,000 nuclear weapons were on a hair trigger. “Nuclear winter,” warned the bestselling The Fate of the Earth, could destroy all life, leaving “a republic of insects and grass.”

The dread crept into all corners, even a child’s.

One afternoon in Manchester, Maine, Samantha Smith was talking with her mother. Will there be a war, the 10-year-old asked. Jane Smith shared her daughter’s concerns, then showed her an article about the new Soviet premiere. Yuri Andropov was already cracking down on dissidents. Press and pundits feared the worst.

"If people are so afraid of him,” Samantha asked, “why doesn't someone write a letter asking whether he wants to have a war or not?"

"Why don't you?” her mother replied.

Dear Mr. Andropov,

My name is Samantha Smith. I am 10 years old. Congratulations on your new job. I have been worrying about Russia and the United States getting into a nuclear war. Are you going to vote to have a war or not. . .

Samantha’s father mailed the letter to the Kremlin. The winter got colder.

In Europe, more missiles, more protests. In Lawrence, Kansas, an upcoming movie staged the nuclear nightmare of “The Day After.” In March, President Reagan called the Soviet Union “the evil empire.” Samantha’s letter got no response. Then in early spring. . .

Саманта Смит

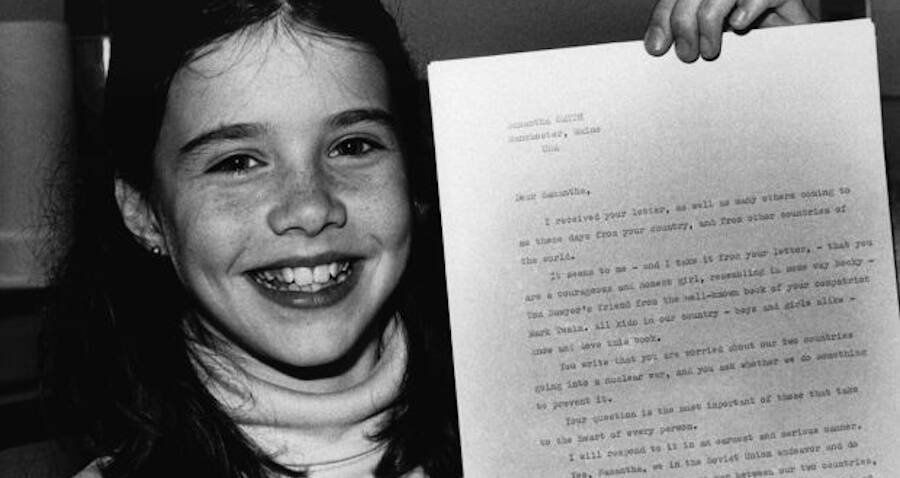

A UPI reporter, calling her school, told Samantha that her letter was in the Soviet newspaper Pravda. So why no answer? Hadn’t she added “P.S. Please write back?” Samantha wrote to the Soviet embassy in DC. Two weeks later, a letter came from the Kremlin.

Dear Samantha,

I received your letter. . .

The new Soviet premiere compared Samantha to Becky Thatcher, the Mark Twain heroine “well known and loved in our country.” A history lesson followed — how the USSR, as an American ally, had lost millions of lives in World War II. “I hope that you know about this from your history lessons in school. And today we want very much to live in peace, to trade and cooperate with all our neighbors on this earth. . .”

Then Andropov dropped a bombshell. “I invite you, if your parents will let you, to come to our country, the best time being this summer. You will find out about our country, meet with your contemporaries, visit an international children's camp — Artek — on the sea. And see for yourself: in the Soviet Union, everyone is for peace and friendship among peoples.”

Hungry for hope, newspapers and networks interviewed the girl from Maine. “The reporters kept asking if I was nervous about all this, which I wasn’t, but I wondered if I was supposed to be nervous.” But wasn’t this just propaganda? Arthur Smith consulted the State Department. Should they go?

That was “a family decision,” officials said, but be advised that the Soviets “would continue to use the invitation for political and propaganda purposes.” Smith knew “the Soviets had their own motives,” but he could hardly say no to Samantha.

On July 7, 1983, the Smiths landed in Moscow. For two weeks, “the world media followed her everywhere,” remembered Valery Kostin, director of the youth camp where Samantha spent five days. “Some were looking for negative propaganda, but this girl was absolutely innocent. At press conferences, she answered questions with a smile. At first she looked to her parents to see how she should answer, but then she just answered on her own. It was incredible.”

The tour included the Bolshoi Ballet, Red Square, Leningrad, and the youth camp where Samantha refused private lodging and bunked with other girls.

“Sometimes at night we talked about peace,” Samantha remembered, “but it didn’t really seem necessary because none of them hated America, and none of them ever wanted war.”

Finally, Samantha flew home. Again America’s youngest ambassador” made headline news. But had it all been a ploy?

Hardliners insisted the girl had been used. On a TV talk show, Arthur Smith was accused of setting up “the greatest propaganda stunt the Soviets could hope for.” He disagreed. The trip, he said, introduced the Soviet people to “the independent spirit of the American child.”

Moving into sixth grade, Samantha appeared in a sitcom, spoke at a youth conference in Japan, and wrote a memoir. Meanwhile, US-Soviet exchanges — among families, colleges, and camps — began to reach across the divide. Yuri Andropov, too ill to speak to Samantha except by phone, died. His replacement was Mikhail Gorbachev.

You may know the ending. In August 1985, Samantha and her father were flying home from taping another sitcom. It was a rainy night. Radar failed. Pilots were inexperienced. The small plane hit some trees. . .

A thousand people attended the funeral. Reagan sent condolences. Gorbachev added, “Everyone in the Soviet Union who has known Samantha Smith will forever remember the image of the American girl who, like millions of Soviet young men and women, dreamt about peace.”

Valery Kostin, the Soviet camp director, soon moved to Maine where he continues to arrange US-Russia exchanges. Like other survivors of that coldest winter, he will never forget Samantha.

“This girl arrived like an angel and changed the way Russian people viewed the United States. With her childish, naive voice, she delivered a very powerful message.”