THE GENIUS, HIS WIFE, AND THE BOMB

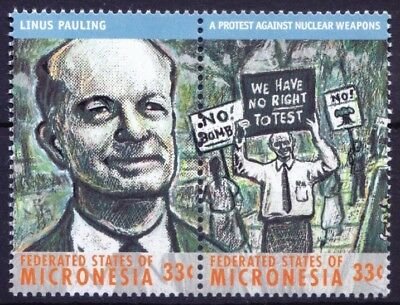

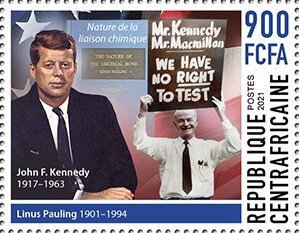

THE WHITE HOUSE, APRIL 1962 — Mushroom clouds were rising again. A moratorium on nuclear tests had broken down. Again the radioactive fallout. Again the spread of deadly Strontium 90. Outside the White House, protestors picketed.

When the picketing ended, most went home, but one protestor — and his wife — donned formal attire and stepped into the East Room. There Linus and Ava Helen Pauling joined other Nobel laureates. Physicists, chemists, novelists, poets. Meeting Pauling, President Kennedy said, “I’m glad you decided to come inside.”

From the ashes of Hiroshima, scientists bore a heavy burden. “The unleashed power of the atom has changed everything save our modes of thinking,” Einstein wrote, “and we thus drift toward unparalleled catastrophe.” Many scientists shrugged. “You don’t have to be responsible for the world that you’re in,” Richard Feynman said. But those who shouldered the burden found a lighting rod in Linus Pauling.

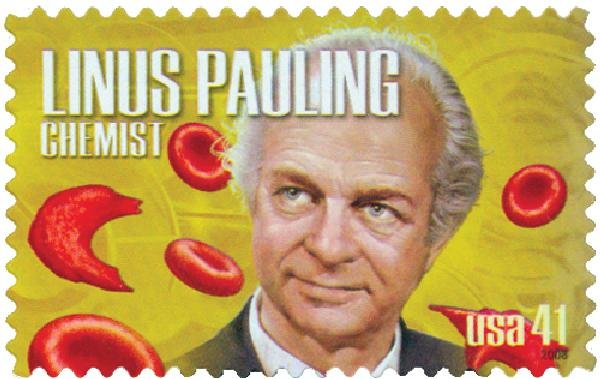

From an Oregon boyhood playing with chemistry sets, Pauling rose to the pinnacle of science — the Nobel Prize. Pauling applied the mysteries of quantum theory to the valences and bonds of the elements, paving the way for DNA and other discoveries. But he might have remained a quiet genius if not for his wife.

At Oregon State, Ava Helen Miller was Pauling’s brightest student — dedicated, fascinated, committed to social justice. But he was a rising chemist with no interest in peace. Their love — call it chemistry — led to a lifetime of mutual support, yet while raising four children, Ava Helen kept her politics to herself.

During World War II, she said little when her husband did weapons research. Explosives. Rocket propellants. A patent for an armor-piercing shell. But after Hiroshima, when he was asked to speak about the bomb and its implications, she protested.

“ Linus Pauling, Now there’s a genius!”

“When you talk about the nature of war and the need for peace, you are not convincing because you give the audience the impression that you are not sure about what you are saying.”

“Those sentences changed my life,” Pauling remembered. Chided by Ava Helen, he decided to devote half his time to studying the bonds that link humanity. And together, the Paulings pursued peace.

She marched, wrote letters, chaired peace groups. He used his name, boosted by the Nobel in 1954, to rally scientists. His work alarmed McCarthyites who had his passport revoked, but he continued to speak out.

In May, 1957, Pauling circulated a petition. “We, the scientists whose names are signed below, urge that an international agreement to stop the testing of nuclear bombs. . . ”

With 2,000 signatures, Pauling asked President Eisenhower for a meeting. He was refused. The following winter, the Paulings presented the petition, signed by 11,000 scientists in 50 countries, to U.N. Secretary Dag Hammarskjold. That year, Pauling published No More War!

“A new type of thinking is essential if mankind is to survive,” Pauling wrote. The U.N., he said, should establish a World Peace Research Organization. The president’s cabinet should have a Secretary for Peace budgeted at ten percent of the Pentagon’s billions.

In 1960, a Senate subcommittee grilled Pauling, calling him “the number one scientific name in virtually every major activity of the Communist peace offensive in this country." Pauling stood his ground. He was no Communist, he testified, merely a concerned scientist. “In my actions about social and political questions and the great question of preventing war and preserving the peace in the world I have served no one but the whole of humanity.”

More protests and petitions. Personal letters to Kennedy and Khrushchev, even to Jackie Kennedy. “Your children, along with all the other children in the world, are laying down in their bones, along with the calcium, Strontium 90. If more bombs are tested, the Strontium 90 will increase.”

When other scientists lost hope, Pauling continued “because I had to retain the respect of my wife.” And on October 10, 1963, the world awoke to a new dawn. A Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty banned atmospheric testing. That afternoon, a call came from Norway. Pauling had won a second Nobel — for peace. Grateful for the honor, he said he wished his wife could share it.

The Peace Prize, Pauling said, meant more than his Nobel for chemistry “because it means there is a feeling that i have been doing my duty to my fellow human beings.” Hardliners sneered at this award to “a placarding peacenik,” but Pauling leveraged it into more influence.

Throughout Vietnam, on into the 1980s, Pauling and his wife remained on the front lines of peace. After Ava Helen died, Pauling marched on alone. Letters to Reagan, Andropov, and after the Gulf War began, to President Bush. “FIGHT AGAINST THE IMMORALITY AND BARBARISM OF WAR!”

Throughout his work, Pauling credited Ava Helen. “I'm sure that if I had not married her, I would not have had this aspect of my career -- working for world peace.”

Pauling died in 1994. He is buried in Oregon beside his wife. Let their epitaph be the New York Times comment on Pauling’s second Nobel: “While others have spoken for nations, ideologies, and above all, power, Linus Pauling spoke for Man. If the human race is to be spared the ultimate holocaust, it too will speak, and for a long time to come, of Linus Pauling.” And of his wife.