un-abridged -- a delightful romp through dictionaries

un-abridged: the thrill of (and threat to) the modern dictionary, by Stefan Fatsis, Atlantic Monthly Press, 416 pp.

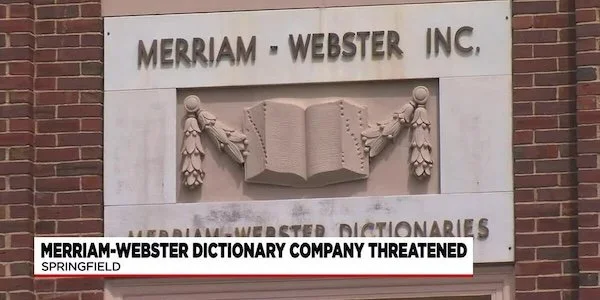

SPRINGFIELD, MA — Deep in the labyrinth of this neglected city stands a monument to the American language and its wackdoodle history. The monument is not open to the public but its legacy is both online and in danger.

Since before the Civil War, Merriam-Webster has held the keys to our linguistic kingdom. In 2025, Webster’s remains “the last dictionary standing,” and its keys are kept in “rows of chest-high, brick- or tan-colored metal filing cabinets of varying sizes and styles that stretched around the editorial floor like dominoes.”

On file, from “AAA batteries” to “Zyrtecs,” are some 16 million “cits,” 3 x 5 index cards citing specific uses of every word that made the cut, proved its common usage, and ended up in a Merriam-Webster dictionary. Seeing the cabinets for the first time, Stefan Fatsis “swooned.”

un-a-bridged is as much a journey as a book. Word freak Fatsis, having written a best-selling book about Scrabble (Word Freak), turns his deep curiosity to the dictionary. What begins as a “spelunk” into the “quirky and charming subculture of word lovers” becomes part odyssey, part funeral dirge.

The book recounts Fatsis’ ten-year flip-flop between Webster’s quaint Springfield office and the emerging digital domains of online dictionaries, databases, algorithms, and, of course, AI. While Fatsis’ focus includes a little too much digital for my taste, his wit and wordplay make un-abridged a delightful but disturbing romp.

After getting himself “embedded” at Merriam-Webster, Fatsis takes readers through the arduous work of lexicography. In a world where new words are daily spun out of social media and the whims of anyone with a smart phone, what qualifies as a “word?” Which new coinages deserve to be enshrined in a dictionary and which will be forgotten within the month?

Fatsis peoples his book with editors, linguists, and fellow word freaks who decide what makes the cut. Usage is the measure. To be given the imprimatur of Merriam-Webster, a new coinage must have several citations of its use. Cromulent, first used in “The Simpsons,” struggles for acceptance. Likewise sportocrat, fleek, and vajazzle. But shapeshifter, sheeple, and dozens of others are welcomed into the fold.

Along with wordplay, Fatsis does his homework, growing from mere “cosplaying as a lexicographer” into a genuine “lexicographer in training.” Determined to get several definitions into Merriam-Webster’s, he digs for citations, scans the Internet, and comes up with. . .

Safe space. Micro-aggression. Alt-right and more. And when, after nit-picking changes by editors, his definitionis end up online, Fatsis is thrilled. “I wrote something that was worthy of entry into the dictionary. . . I created some knowledge.”

But as he dives deeper into the cits, Fatsis sees Merriam-Webster losing the battle against the internet. The latest print dictionary he hoped to chronicle is canceled. Editors are laid off. The number of full-time lexicographers in America drops from 200 to 50, leaving Fatsis to wonder. “At a time when technology is reshaping the ways people conceive, use, share, and relate to. . . language, what does a dictionary even mean?”

To answer that question, Fatsis leaves Merriam-Webster and heads for the digital world. His quest takes him to Oxford where he watches the prestigious OED face the same threat. He visits private lexicographers and attends language conferences, including Word of the Year. He ends up at the Bay Area office of dictionary.com filled with huge iMacs and bright young technophiles, but not a single book.

Fatsis always returns to Merriam-Webster, but not often enough. Whole chapters stew in the swamp of politics and political correctness, citing how certain buzzwords — woke, critical race theory, cancel culture — are weaponized. Coming from the safe space of Webster’s offices, these battles are painful to explore. You keep wishing Fatsis would return to the filing cabinets. You keep wishing dictionaries were still big and bulky and, in all things, the final word.

But as Fatsis makes clear, “the English language is Jell-O, slippery and mutable and forever collapsing upon itself.” And un-abridged skillfully defines the battles for a language that has always been quaint, nerdy, and, alas, political.

The fate of the dictionary, historian Michael Adams notes, “has to do with what kind of America we want to be. . . The dictionary, though it may seem marginal to some people, is an icon of America.” un-abridged takes you behind the icon, makes you care about it, and leaves you grasping for words.