THE CAMERA AS WEAPON

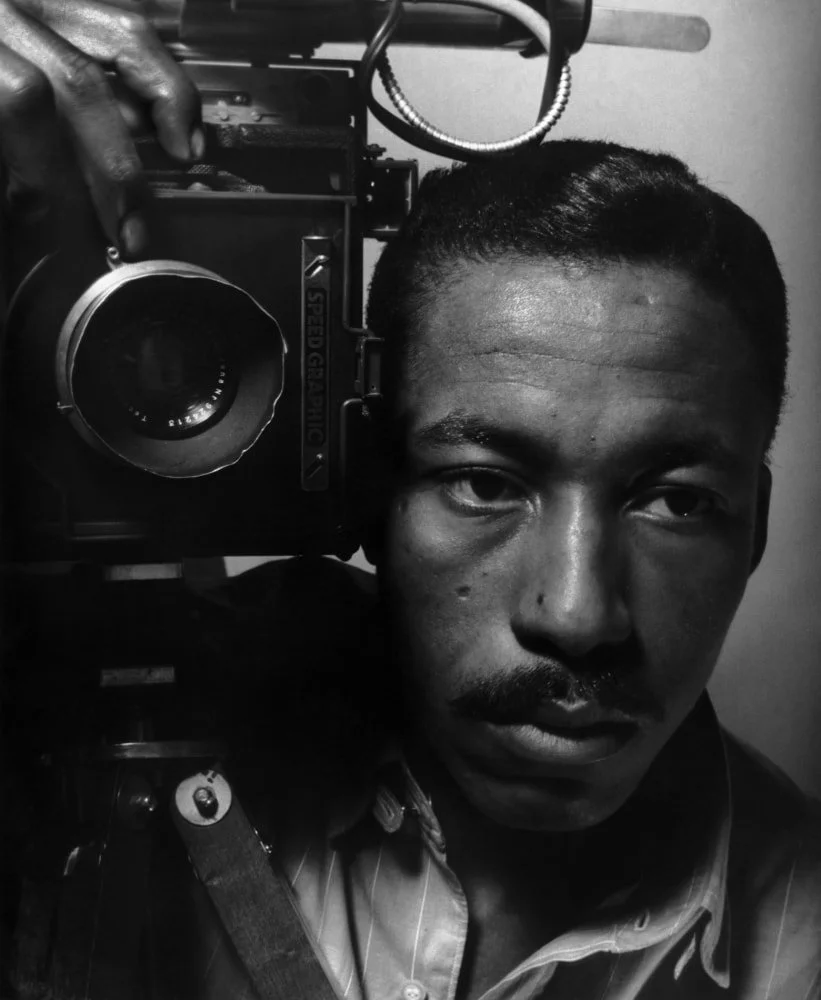

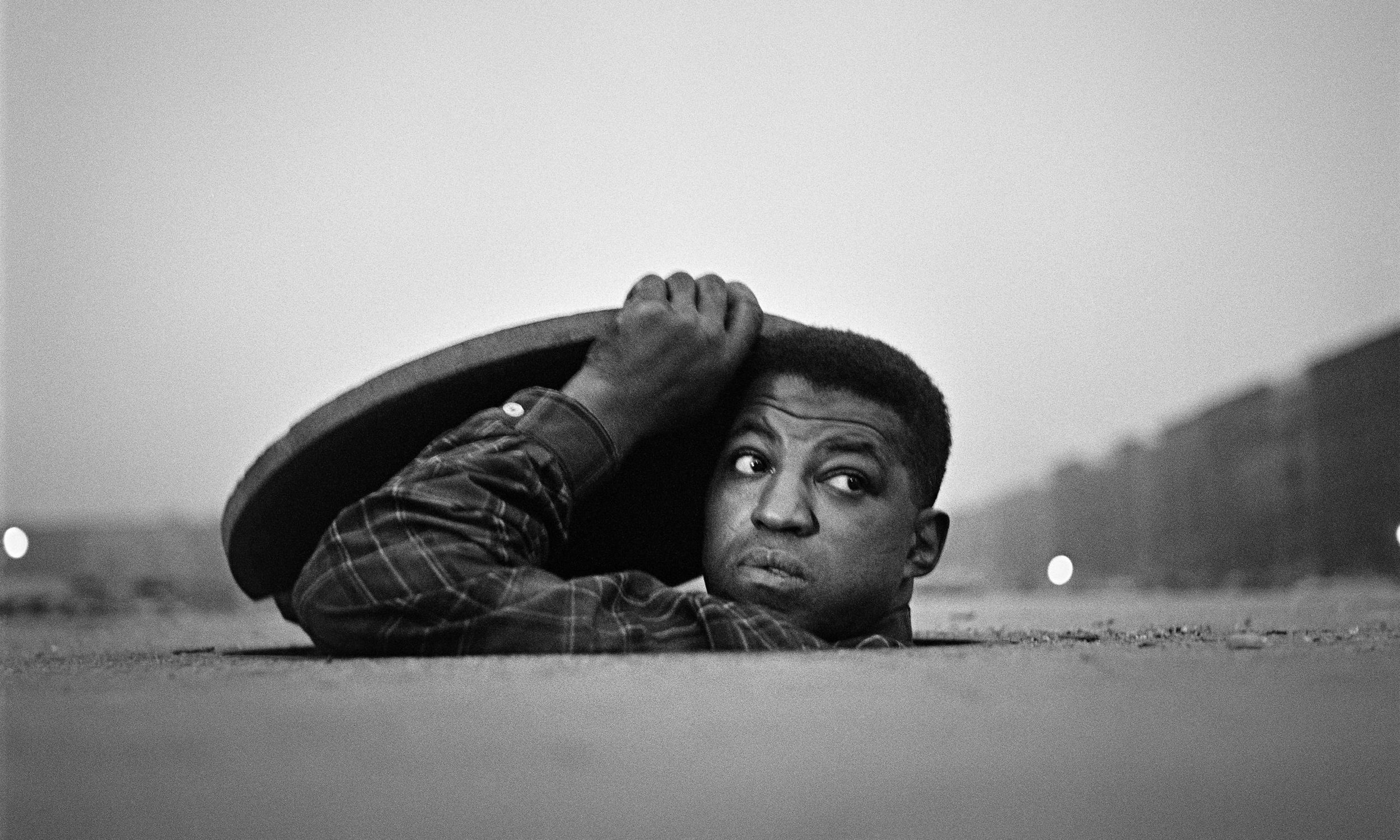

WASHINGTON, D.C. — 1942 — New in town, the young photographer roams “this radiant city.” He is rejected at every turn. “White restaurants made me enter through the back door. White theaters wouldn’t even let me in the door.” But he has “a weapon” — his camera.

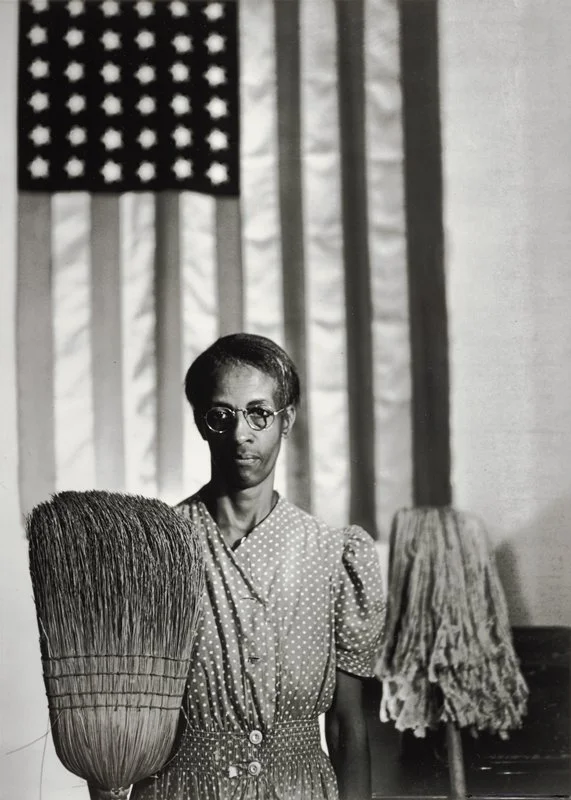

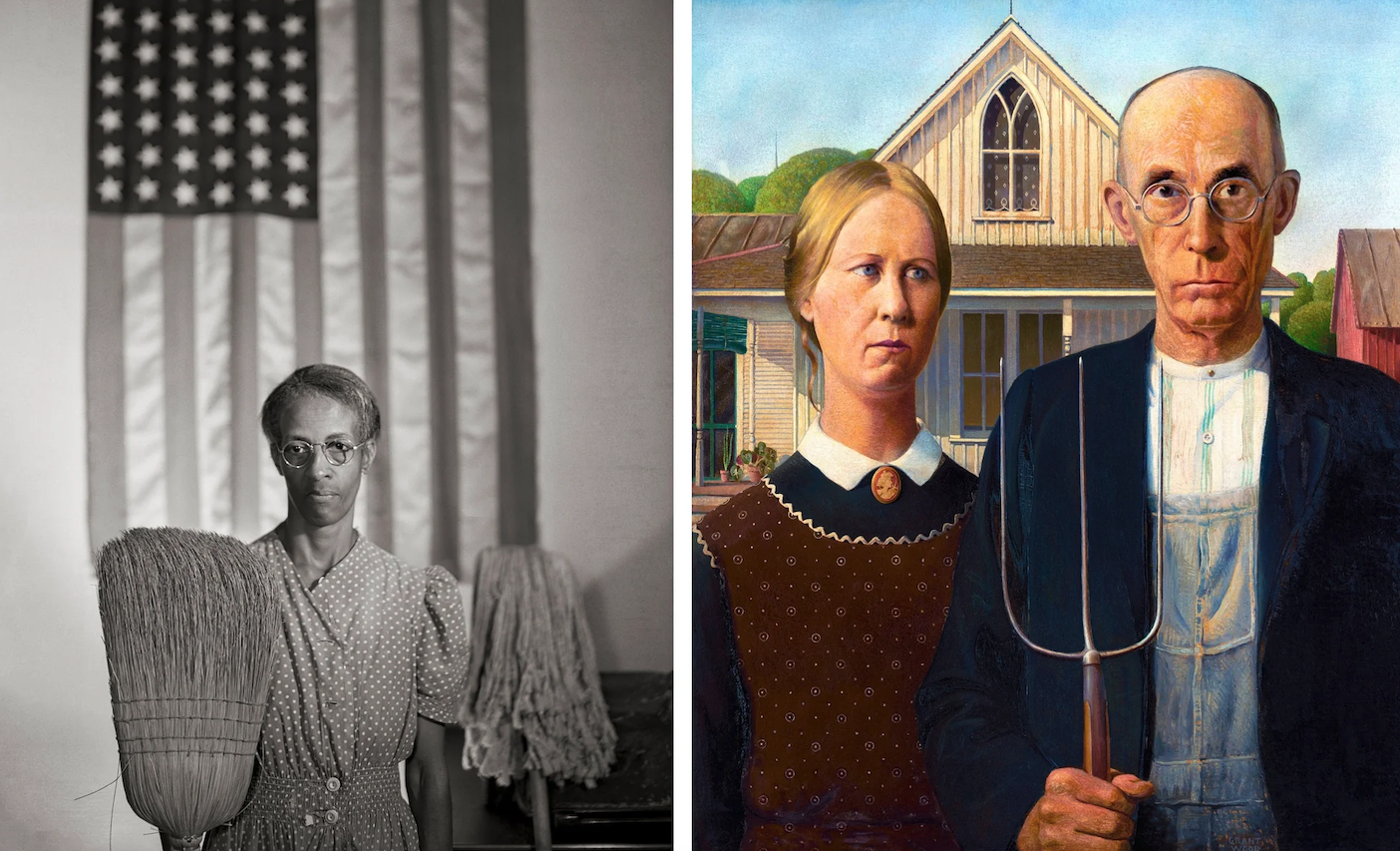

One afternoon at the Farm Security Administration where he had a fellowship, Gordon Parks met the FSA’s “cleaning woman.” Ella Watson told Parks of her life — her father lynched, her husband murdered, her daily toil to care for children and grandchildren. Parks asked if he might photograph Watson, and for the next month he trailed her from job to home to church. One day, he posed her.

Parks’ boss at the FSA thought the photo, “Government Charwoman,” “might get us all fired,” but instead it highlighted a remarkable photographer and his remarkable career.

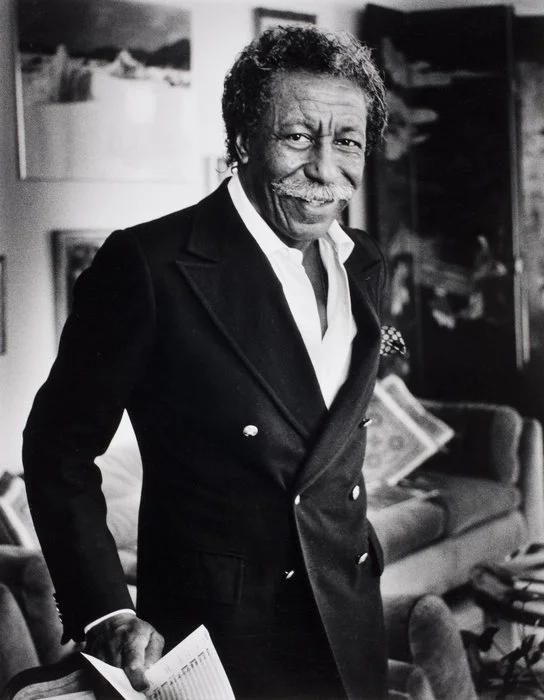

Gordon Parks refused to be confined in racism’s cage. Or any cage. Beyond photos and movies, he composed concertos, painted, and published 15 books, including memoirs, poetry, and two novels. “I suffered evils,” he said, “but without allowing them to rob me of the freedom to expand.”

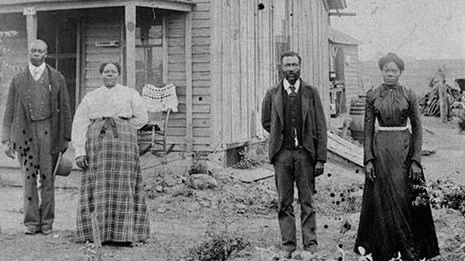

The expansion began on a Kansas farm tended by his father, one of the “Exodusters,” blacks who fled the South for the Midwest. Born in 1912, Parks was the youngest of 15 children. He somehow survived Jim Crow, once swimming underwater to escape three white boys who threw him in the river expecting him to drown. After his mother died, Parks was sent to live with his sister’s family in Minneapolis, but arguments soon had him living on the street. He was fifteen.

For the next dozen years, Parks drifted from job to job. A self-taught pianist, he played the piano in a brothel. He worked as a janitor and a Pullman porter. On trains, he cadged magazines left by passengers and soon discovered the migrant photos of Dorothea Lange. Here was poverty bared for all to see. White poverty, though.

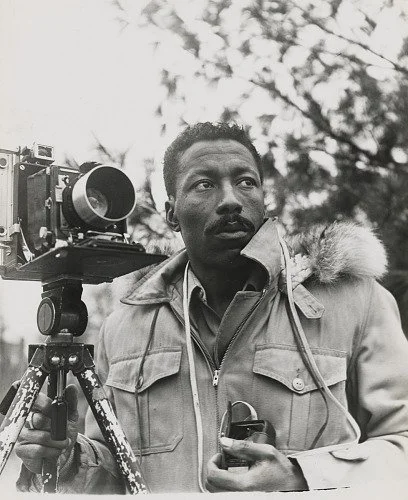

Parks got a book on photography and read it on the train from Minneapolis to Seattle where he bought his first camera for $12.50. “I took it down to Puget Sound to photograph some seagulls, and damned if I didn't fall into the water -- but I held onto the camera!”

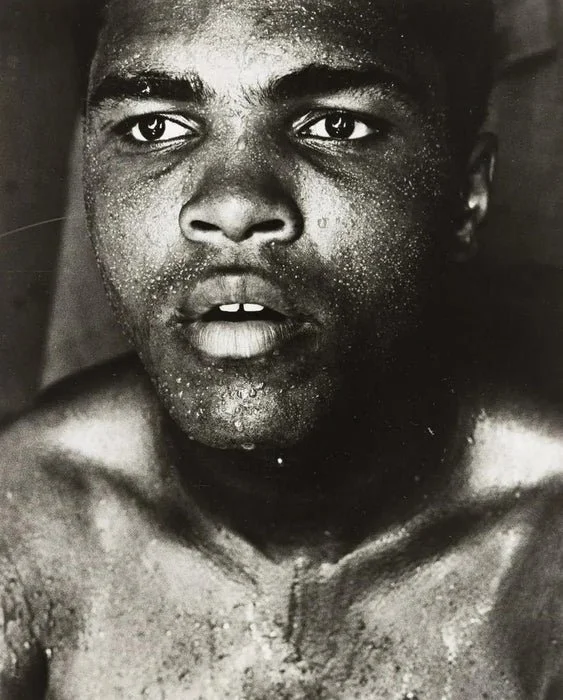

Whatever magic allows a few to look through a lens and see what others miss, Parks had it from the start. His first photos, developed by Kodak workers, drew their praise, and he was soon seeking work for department stores. His early fashion photos caught the eye of Marva Louis, boxer Joe Louis’ wife. She urged Parks to move to Chicago where he began prowling the South Side, capturing the joy and hardship of black migrants. These photos earned him a fellowship at the Farm Security Administration. . .

This standard story makes it look easy. The talented black kid survives Jim Crow, makes his mark, rises, rises. . . But Parks was anything but standard. Freedom, he said, was “not allowing anyone to set boundaries, cutting loose the imagination and then making the new horizons.”

After the war, Parks was hired by America’s top photo magazines, LIFE and Vogue. With an eye for fashion that had him dressing in trench coats, Parks filled the latter magazine with glamour. “You know,” he said, “the camera is not just meant to show misery.”

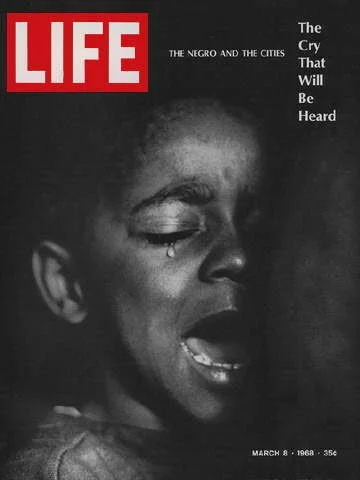

But at LIFE, Parks brought black lives to the coffee tables of white America. If a picture is worth a thousand words, Parks’ photo essays — “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” “The Atmosphere of Crime” — became encyclopedias of outrage.

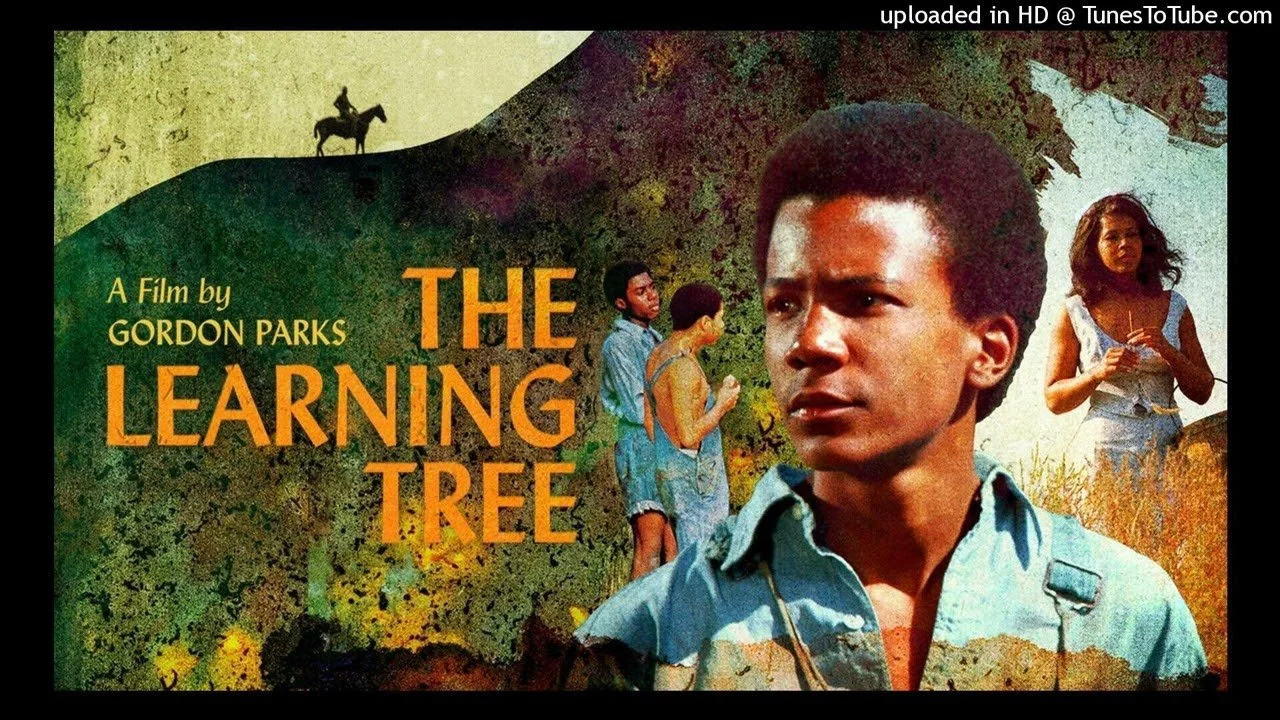

On into the 1960s, Parks befriended and photographed Muhammad Ali, Malcolm X, and Stokely Carmichael. He also wrote his first novel, “The Learning Tree,” and in 1969, directed the film version. The first black Hollywood director. . . Parks also wrote the screenplay, composed the music, and used his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas as the set.

Well-reviewed, “The Learning Tree” earned Parks a second shot. This time, blending his love of fashion with his innate “cool,” Parks created an American icon. Shaft.

Actor Richard Roundtree defined the strong, silent detective but he credited Parks with Shaft’s ethos. “Make no mistake, it was his vision, totally. The character of John Shaft, if truth be known, was Gordon Parks.”

The 1971 film jumpstarted a genre — “blaxploitation.” Parks, who also directed a sequel, was criticized for the films’ macho stereotypes. He did not apologize, “Hell, yes, there's a place for John Shaft. We need movies about the history of our people, yes, but we need heroic fantasies about our people, too. We all need a little James Bond now and then.”

There were few barriers left for Gordon Parks, but he kept expanding, publishing poetry and a second novel, painting, composing and directing a ballet about Martin Luther King.

At 85, Parks said, “I feel I’m just ready to start.” In 2001, the high school dropout and son of a dirt farmer was named “a living legend” by the Library of Congress. Parks lived on to a white-haired, white-mustached 93.

Parks’ photos have been shown in a dozen museums, including the Getty, Boston’s MFA, and the Chicago Art Institute. His films inspired countless black directors, including Spike Lee.

“Government Charwoman” was never published by the government. Parks had to release it himself, in Ebony. He later renamed it “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.” Ella Watson died unknown, but her image continues to haunt America, just as Gordon Parks knew it would.

“I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapons against what I most hated in the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty.”