LOWRIDERS -- CRUISIN' LOW AND SLOW

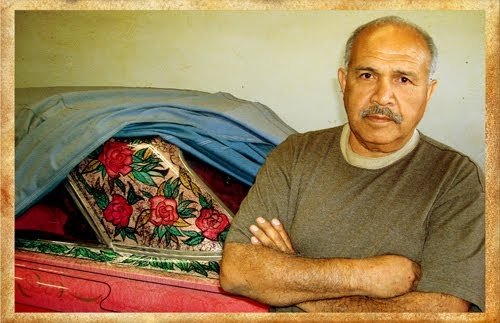

EAST L.A., 1973 — Something was wrong with Jesse’s car. Sure, it was a ‘63 Impala, wire spoke wheels, plush upholstery, riding low to the ground. But roses?

“Jesse put up with a lot of bullshit from other car clubs because of that paint job,” Tomas Vasquez recalled. “They used to dog on him like, ‘How can you put effin’ roses on your car, man?”

Then one night Jesse and fellow “clubbers” ventured into gang territory without permission. No one was hurt, except the car. Smashed by crowbars, Gypsy Rose “got in an accident,” Jesse told friends.

Low Riders are “metal rolling canvases.” Low Riders are also drivers who lavish their cars “with artwork on par with graffiti by Banksy.” And Low Riders tell a story of a community that defied prejudice, challenged local gangs, and finally earned respect.

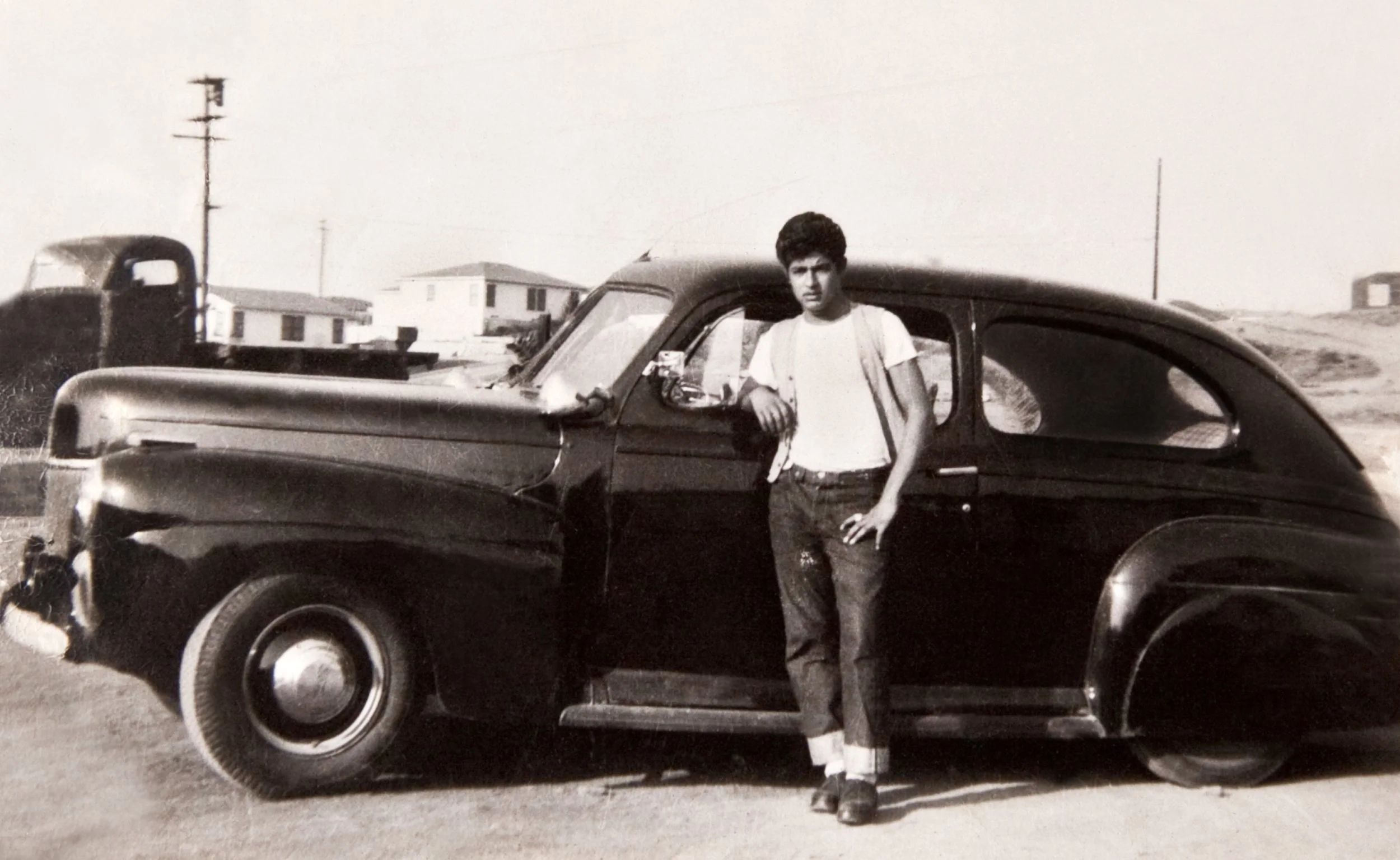

In the late 1940s, Mexican-Americans in East L.A. felt like targets. Still reeling from the wartime Zoot Suit Riots that saw sailors tear through barrios beating up Latinos, locals began to distance themselves from L.A. using the city’s most beloved icon — the car.

Anglos drove cars with rear ends “raked” high. Anglos liked wide tires, big steering wheels. Anglos drove fast. So why not make a four-wheeled Declaration of Independence by doing the opposite.

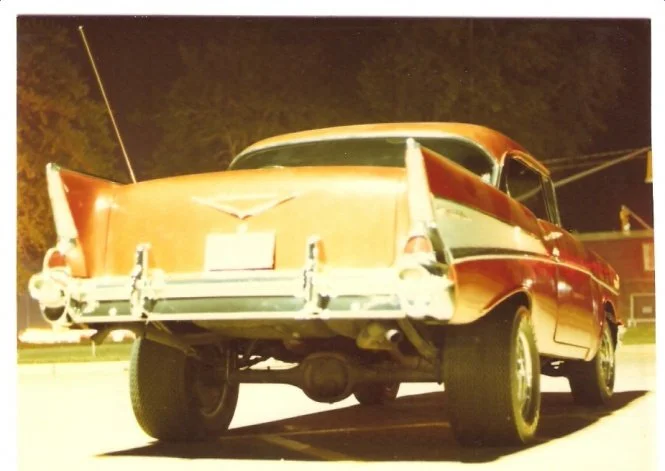

To go low, riders shortened springs in rear suspension. Or put bricks in their trunks. To go slow, they downshifted, turned up the music, and drove as if they owned the street. Add a dazzling paint job, skinny tires, immaculate upholstery, and. . . Vamos.

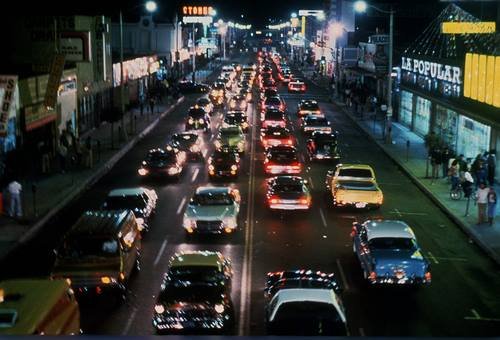

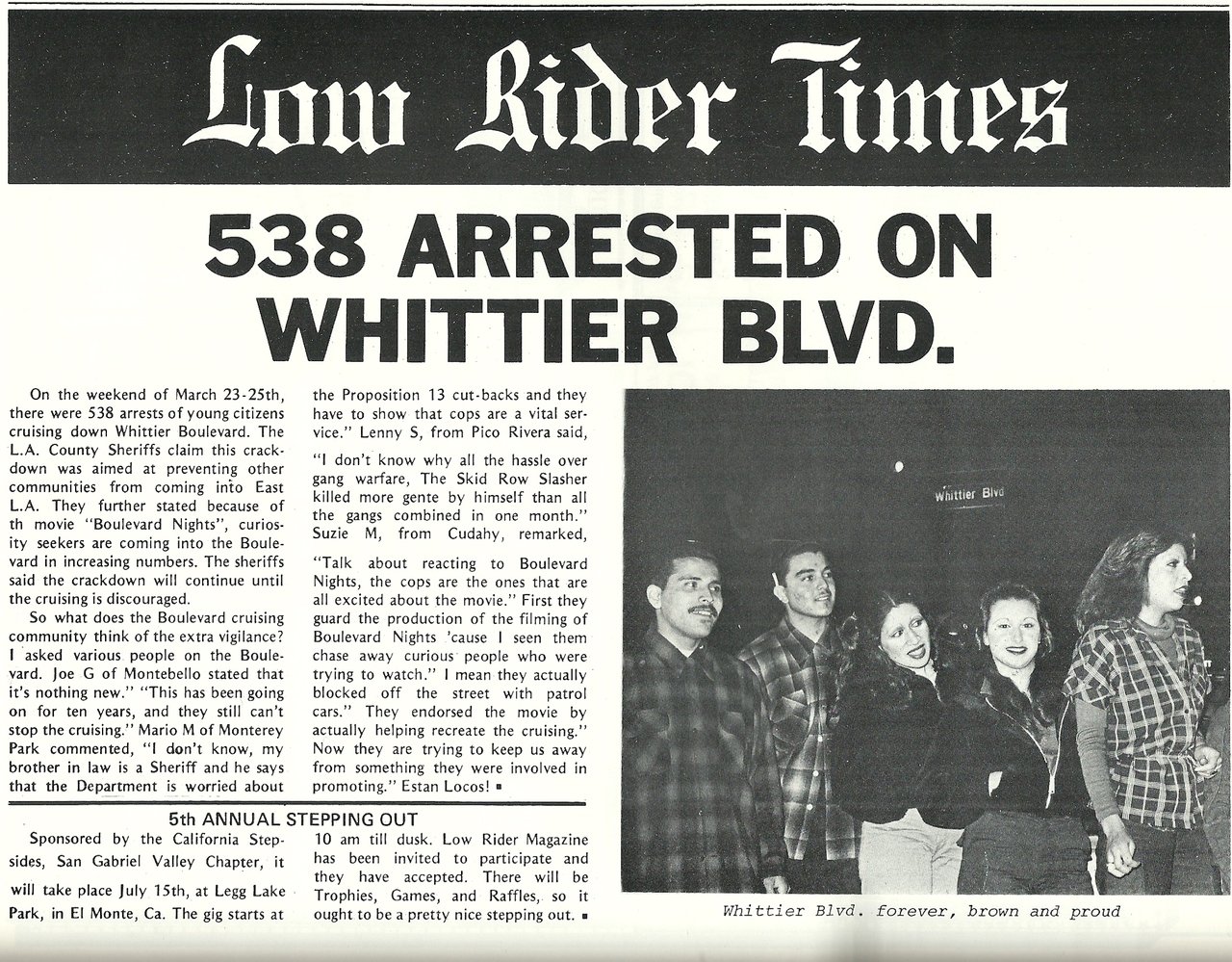

By the late 1950s, Low Riders were cruising “a nightclub and Disneyland all in one place” — Whittier Boulevard. Every weekend evening, this four-lane blacktop lined with taco shops and pawn shops came alive with big cars driving “low and slow, mean and clean.”

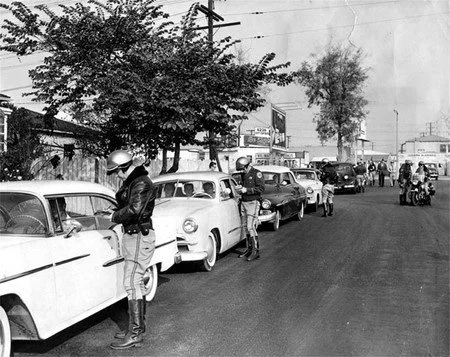

But many Low Riders were also cholos, gang members, putting cops on edge.

In 1958, California banned cars whose chassis rode lower than their wheel rims. Cops ticketed one driver after another. The following year, Ron Aguirre, using air pumps salvaged from a B-52, changed low riding with the flick of a switch.

Now, when cops approached, a Low Rider could raise his car’s rear end and drive off. And when no cops were around, he could make his car hop. Watch:

On into the 1960s, newly formed car clubs broke away from the gang bangers and struggled for respect. “A cholo in his Low Rider wants to instill fear,” Esteban Veloz said. “A car clubber wants to show his class.”

Amazing paint jobs — metal-flaked and multi-layered — became the trademark. The Chevy Impala and its easily modified X-frame became the car of choice. So when Gypsy Rose “got in an accident,” Jesse Valadez took low riding to a new level. He owed it all to his mother.

“There are no people in this world that have something against roses,” Jesse’s mother told him. The destroyed Gypsy Rose was painted with a few dozen roses. The new model would have more, 115 in all. With 2,000 floral leaves. Elaborate scrolling. An 8-inch TV in the console. Candelabra lights in back. Upholstery — pink crushed velvet. And plenty of what Jesse himself had — pride.

Born in Coahuila, Mexico, Jesse came to Texas as a teen, then to East L.A. As disgusted by local gangs as by Anglo prejudice, he became a community leader, talking many young men out of gang membership. It wasn’t just about the car, but Jesse’s Gypsy Rose became the breakthrough.

Seen on the opening credits of the sitcom “Chico and the Man,” Gypsy Rose brought Low Riding to national attention. “Low Rider,” by the R&B group “War,” soon topped the charts. Low Riding spread to California’s Central Valley and to San Jose, where college students started “Low Rider” magazine. Jesse drove on.

“It was like a movie star, being pointed at, looked at. All you heard was ‘Gypsy Rose, Gypsy Rose. . .”

Throughout the 1980s, as California communities banned low riding, the culture spread. Rap and hip-hop eulogized Low Riders. Cops cracked down.

“People didn’t know what a Low Rider was,” said Jesse’s brother Gilbert. “They confused us with the cholos, the gang bangers, which we were not.” Jesse drove on.

Jesse Valadez lived to see Low Riders earn some respect. In movies, in music, in car museums, the Gypsy Rose and other Low Riders became more than symbols of defiance.

“For us, it was something for our culture — to make us feel good, ” said Jesse’s brother Armando, “Because they used to put us down.”

Jesse died in 2011. At his funeral, the Gypsy Rose led a procession of 400 “rolling canvases.” Six years later, recognized as “the Mona Lisa” of Low Riders, the car was displayed on the National Mall in Washington. The Gypsy Rose is now in the Smithsonian’s Museum of American History. So Jesse is still driving.

Most California communities have rescinded bans on low riding. And today’s Low Riders do more than hop. They tilt. They twist. They rise to almost vertical, a feat called “12 o’clocking.” Pride remains a chief ingredient, but Gypsy Rose co-designer Don Heckman recalled another motive.

“Some people say it’s way too overdone, some people say it’s just right, and I say ‘it was just a lot of fun.”