AMERICA'S FIRST PLAYGROUND

CONEY ISLAND, JULY 4, 1947 — As the sun warms the Boardwalk, crowds stream off the subway at the end of the line in Brooklyn. Before reaching Surf Avenue, they smell sizzling hot dogs, steamed clams, cotton candy. Before hearing the ocean, they hear the roar of roller coasters, the toot of a calliope, and the cry of “Step right up, folks!”

There are other things to do on this Fourth. Baseball at Ebbets Field, Broadway shows, movies. But for Americans within reach, there is only one place to spend the holiday.

A generation later, some 400,000 at Woodstock would be an epochal event. But on this one four-day weekend in 1947, 6 MILLION people came to Coney Island. Call it “The Nickel Empire,” call it “The Poor Man's Paradise.” By any name, Coney Island was America’s playground.

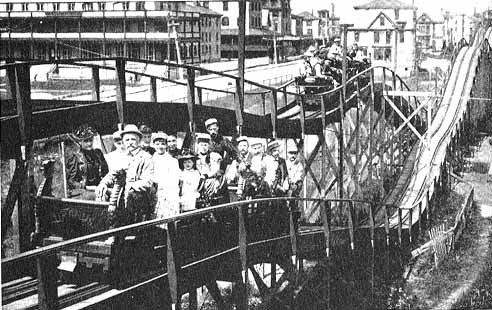

The fun began in 1884 when George Tilyou, who had grown up here selling bottles of genuine Coney Island sand, opened a roller coaster. Top speed was six m.p.h., yet lines stretched around the block.

Coney Island was already crazy and crowded. Splashing in waves, women in full-length dresses and men in tank tops flaunted Victorian morals. Elite hotels served oysters while the hoi polloi wolfed down “Coney Island hots,” America’s first hot dogs. But George Tilyou understood what creates a crowd.

Thousands might crave elegance. Tens of thousands wanted vice -- saloons, prostitution, and gambling in this “Sodom by the Sea.” But millions just wanted to have fun.

In 1897, Tilyou’s new Steeplechase Park amped up the fun. Step right up, folks! Come see Steeplechase, the Funny Place! Don’t be a Gloomster! Be a Steeplechaser!

Steeplechase was an instant hit. Its rough and tumble rides gave couples an excuse to grope and gave everyone a chance to laugh at everyone else. The Wedding Ring perched seventy riders on a great spinning wheel. The Barrel of Love rolled couples in a big drum.

The world had never seen anything like Steeplechase, but the world hadn’t seen anything yet. Because in 1903, Tilyou’s ex-employees built Luna Park.

On opening night, as thousands mingled outside, 250,000 lights blazed on at once. The crowd, still in the age of gas lamps, gasped. Luna Park was a fairyland of moons and lagoons. By day, it looked like a wedding cake, and by night it looked like a dream. Designers had just $11 left when it opened. Six weeks later, they had recovered their $700,000 investment. Coney Island had turned fun into big business.

Soon young men and women weary from a week’s work came here to act as they couldn’t at home, flirting, flaunting bloomers, cuddling beneath the Boardwalk, aka “Hotel Underwood.”

For the next 40 years, Coney Island meant “America.” In "The Jazz Singer," Al Jolson tells his Mammy he'll teach her New World ways. "I'm gonna buy you a nice pink dress that'll go with your brown," Jolson says. "And darlin', I'm gonna take you to Coney Island."

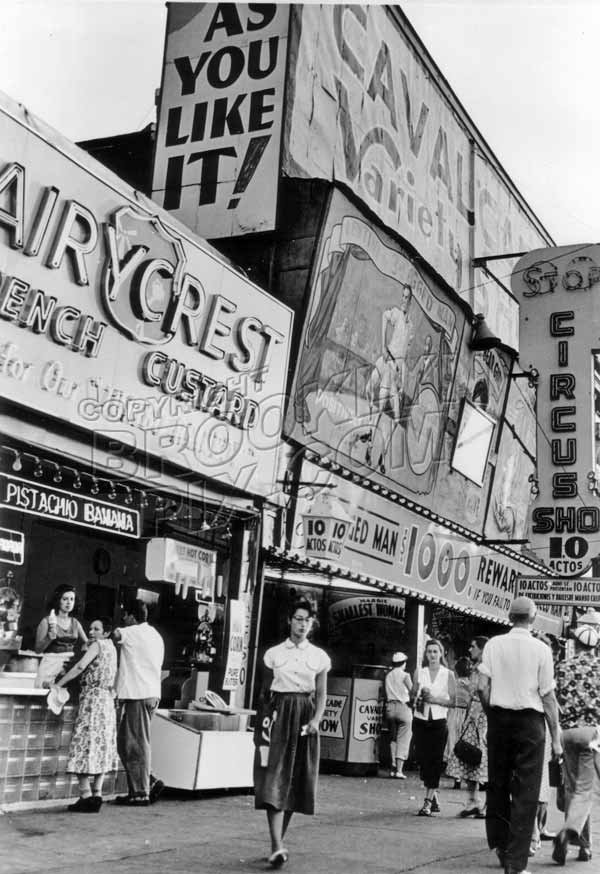

Attractions in the Nickel Empire were bigger, faster, weirder. Horses diving from platforms, Guess Men who guessed your weight, age, occupation, clowns with cattle prods shocking innocent bystanders, all in fun.

Every amusement park had its Ferris Wheel, but only Coney had the Wonder Wheel with cages sliding along tracks inside the 150-foot disk. And once it was moved from the 1939 World’s Fair, only Coney had the Parachute Jump, dangling you 250 feet above the Boardwalk until. . .

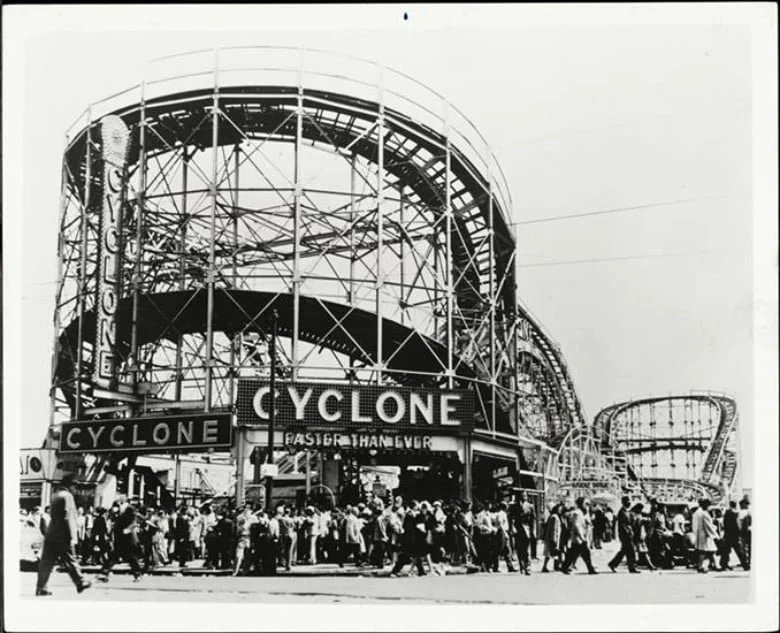

Pumping up the adrenalin, Coney’s showmen built roller coasters with hair raising names -- the Tornado, the Comet, the Cyclone. With its 60 m.p.h. plunge, the Cyclone drew lines five hours long. Charles Lindbergh called the coaster "a greater thrill than flying an airplane."

By the late 1930s, Coney's five-month season drew 25 MILLION people, more than all the baseball games around the country. By then, this small strip of sand hosted: the world's two largest fun parks, 60 bathhouses, 13 carousels, 11 roller coasters, two wax works, six penny arcades, five tunnel rides, 20 shooting galleries, and 200 snack bars and restaurants.

But fun is fleeting, and the fun finally ended at Coney. In the 1950s, air conditioning and TV kept people at home, while Disney and other imitators made Coney seem passé. The Boardwalk remained, but the thrill was gone.

Last week, I rode the subway to the end of the line in Brooklyn. Expecting a ghost town, I found a few ghosts. Above the Boardwalk, the Parachute Jump loomed like an exploded Eiffel Tower, but no one dropped from its heights. Yet though part ghost town, Coney Island is also part Phoenix.

The Cyclone, condemned in 1969, was saved when fans signed petitions. Nearly 100 years old, the coaster thrills a new generation of white-knuckled riders. Across the street, The Wonder Wheel still sends riders snaking along its steel tracks.

I ate a hot dog at Nathan's and strolled the Boardwalk, eavesdropping on conversations in Russian, Khmer, Spanish, Arabic, and English.

Weekend crowds now number in the thousands, not the millions, but the spirit of the old place — part fun and part freak show — survives. Each June, the annual Mermaid Parade fills Surf Avenue. Each summer night, the lights of Coney Island still shine.

"Coney Island is much smaller than it used to be," said Dick Zigun, who turned a Yale Drama School degree into a career running sideshows here, “but it's doing a good job of hanging in there."