THE WOMAN WHO NURTURED THE MODERN

CHICAGO, 1912 — Peering into a jungle of rail yards and slaughterhouses, one poet saw modernity rising.

Chicago architects were crafting a new breed of building — the skyscraper. The Chicago Art Institute was hanging cutting-edge art. Biplanes soared overhead. Model-T’s clogged Michigan Avenue. But poetry?

“The well of American poetry seemed to be thinning out and drying up,” Harriet Monroe recalled, “and the worst of it was that nobody seemed to care.”

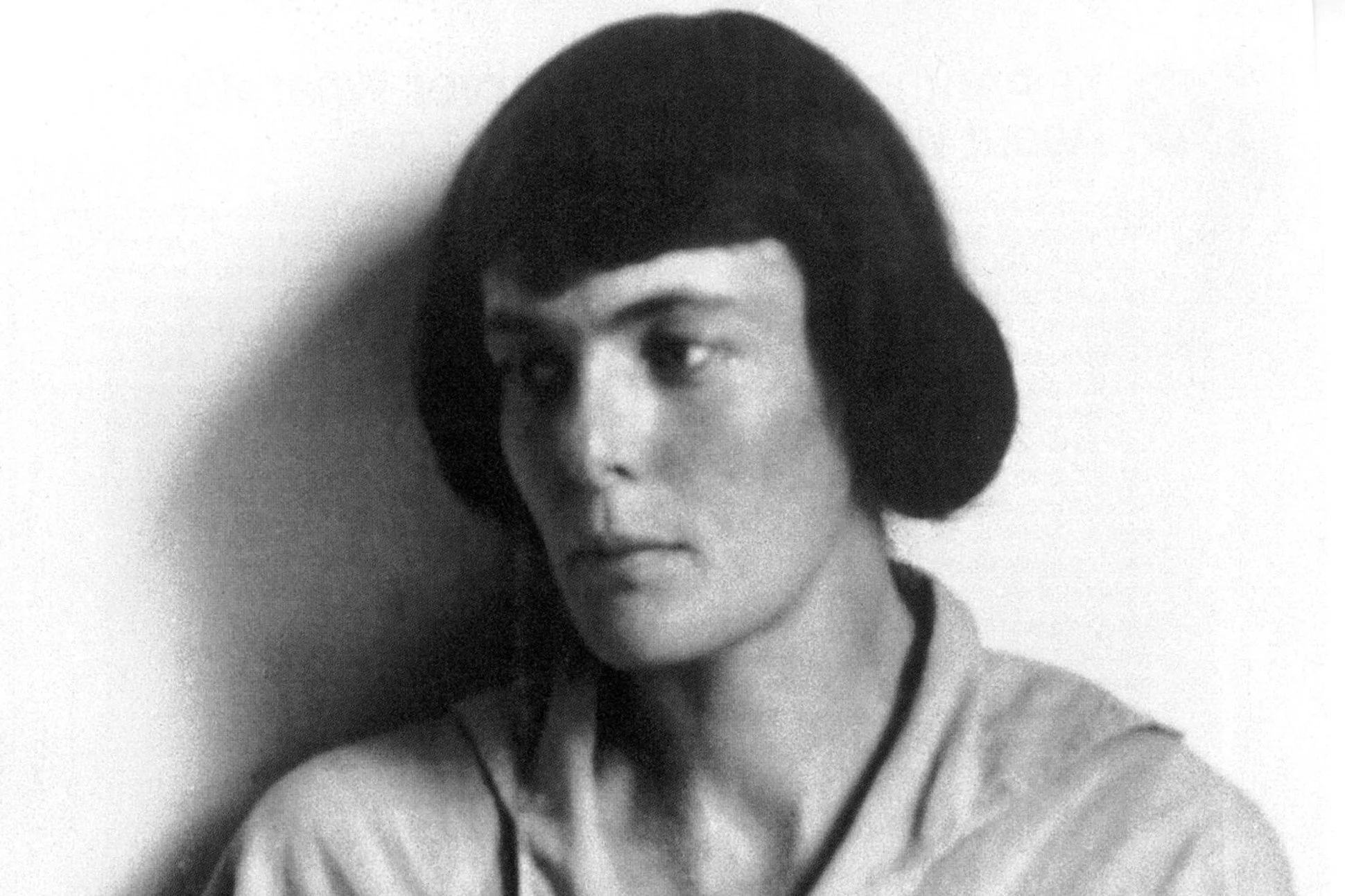

Harriet Monroe was an unlikely modernist. Born in the age of Lincoln, she grew up reading Shakespeare and Dickens, Byron and Shelley, all “friends of the spirit to ease my loneliness.” Graduating from stodgy academies, Monroe wrote florid verse for small magazines. Paid pennies, if at all, she worked as an art critic to support her poetry habit. And she seethed.

“The minor painter or sculptor was honored with large annual awards in our greatest cities, while the minor poet was a joke of the paragraphers, subject to the popular prejudice that his art thrived best on starvation in a garret."

Then in the summer of 1912, Monroe put out a call for “an audacious advance vote of confidence.” Chicago businessmen, professors, teachers were asked to cough up $50 to support a new magazine — Poetry.

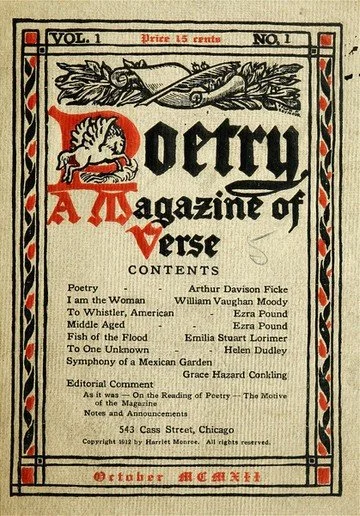

When more than 100 responded, the first issue came out that fall. Crusty old Easterners scoffed at “poetry in Porkopolis,” but young poets flocked to Monroe’s faith and to a wide open ethos she called “the open door.”

“She invented a box, you could say,” a later editor observed, “and promptly sent to work thinking outside it.”

That first issue included poems by Monroe and traditional poets using traditional tri-partite names. Grace Hazzard Conkling, William Dudley Moody, etc. But two works came from a poet named Pound.

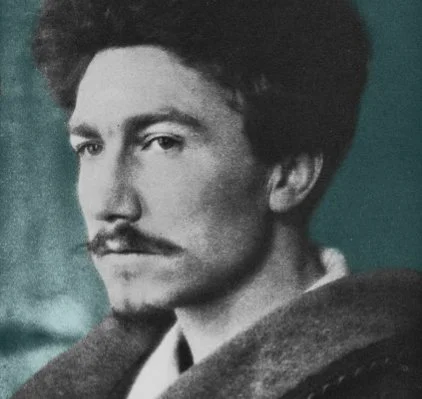

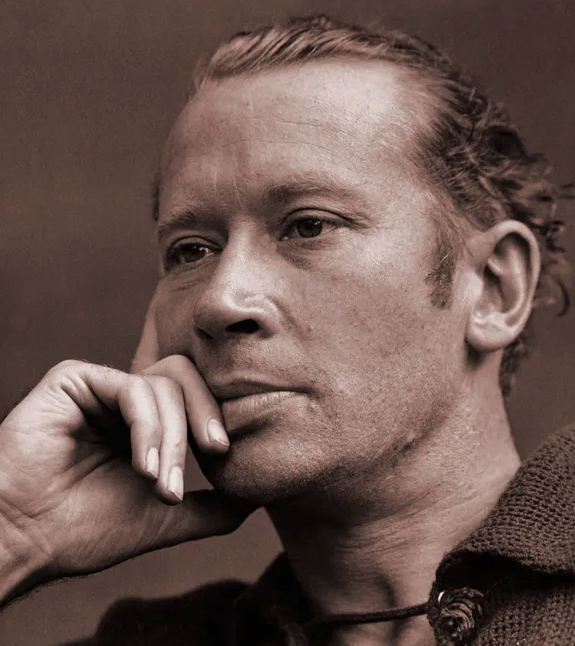

Artists, Ezra Pound wrote, are “the antenna of the race.” Tuning in from London, Pound saw Poetry as sparking an American Renaissance. Monroe made Pound her “foreign correspondent,” and together they modernized, streamlined, and liberated American poetry.

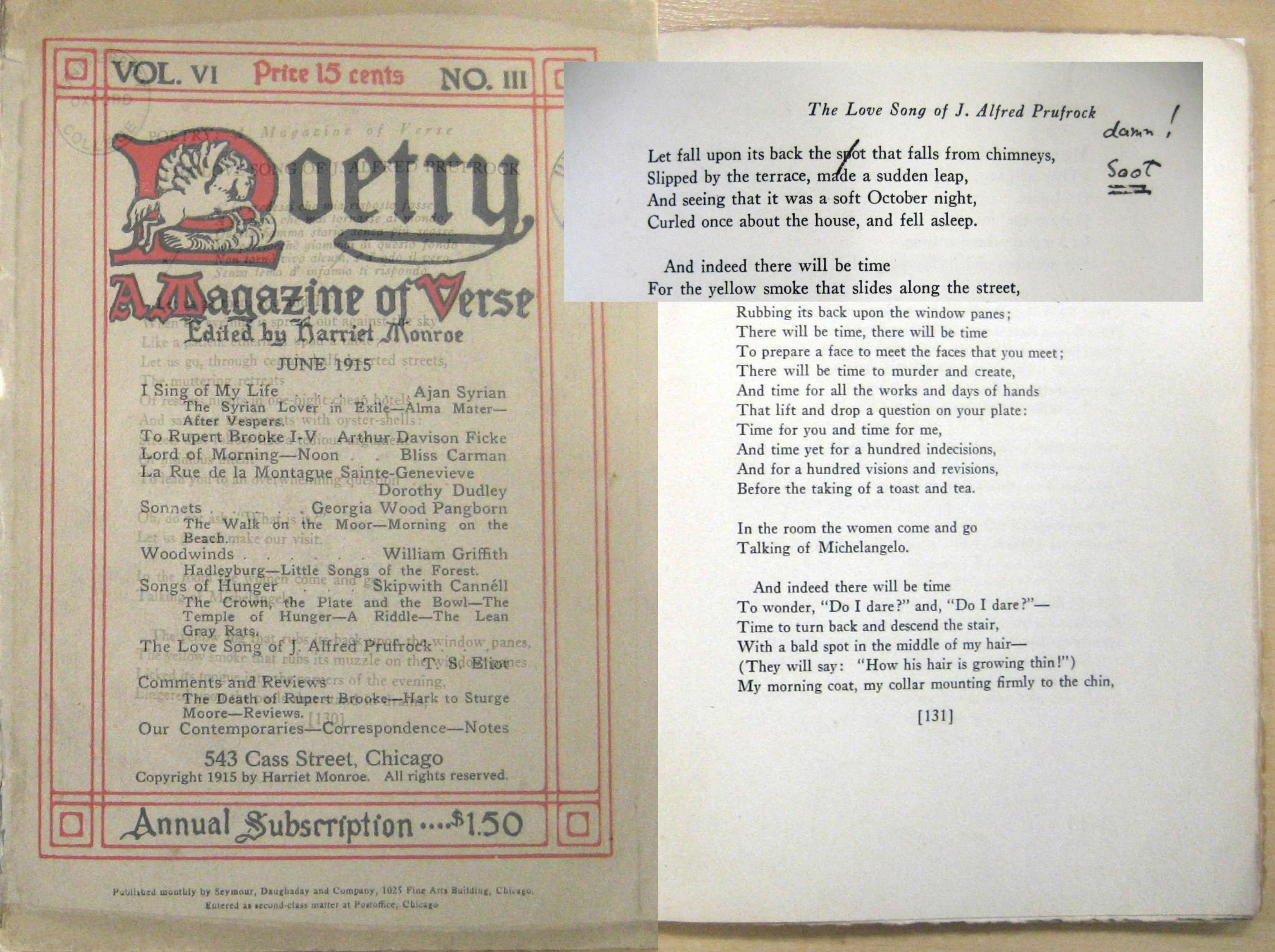

“An American called Eliot called this P.M.,” Pound wrote to Monroe in 1914. “I think he has some sense.” In 1915, having already published future Nobel laureates William Butler Yeats and Rabindranath Tagore, Poetry debuted Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky. . .

This singular poem, Monroe wrote, “swept away Victorian excesses and weaknesses—all the overemphasis on trite sentiment with its repetitions and clichés.”

Poets were ecstatic, yet Poetry struggled. Monroe, then in her 50s, worked tirelessly without a salary. When her day job conflicted, she quit, gave herself a $50 monthly stipend, and struggled on. Her tiny office included no running water so she made coffee in a vacant lot out back, on a wood fire.

Through war, pandemic, and social strife, Monroe offered readers “a place of refuge, a green isle in the sea, where Beauty may plant its garden, and Truth, austere reveler of joy and sorrow, of hidden delights and despairs, may follow her brave quest unafraid.”

When critics charged that Poetry published “minor poets,” Monroe urged them to “remember that Coleridge, Shelley, Keats, Burns, were minor poets to the subjects of King George the Fourth, Poe and Whitman to the subjects of King Longfellow.”

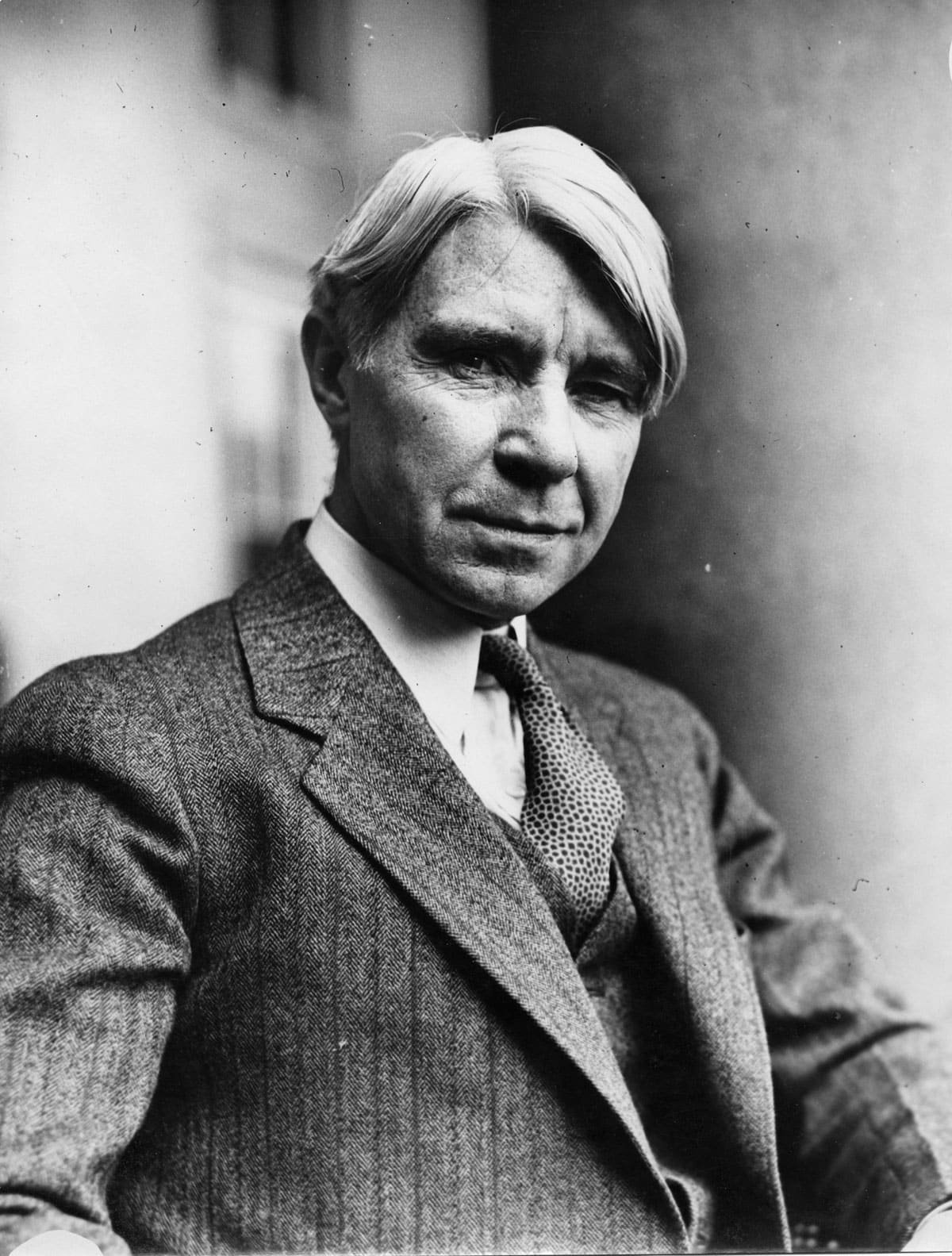

As America surged into the 1920s, the little magazine in Chicago captured modernity in verse freer than anyone had ever seen. Along with Pound and Eliot, Poetry brought Americans to Carl Sandburg, e.e. cummings, Wallace Stevens, Edna St. Vincent Millay, H.D., and William Carlos Williams.

“The histories of modern poetry in America and of Poetry in America are almost interchangeable, certainly inseparable,” poet A. R. Ammons noted.

Monroe upped her monthly stipend to $100, but in 1930 she warned readers that Poetry’s next issue might be its last. Small contributions kept the journal alive, even after Monroe, at age 75, set out for Machu Picchu, only to die en route.

Through the modern, the neo-modern, and the post-modern, Poetry struggled on. At one point during the 1950s, the magazine had just $100 in its coffers. “How I do hope that the millionaire will yet come forward,” Monroe had written. Finally. . .

Ruth Lilly was heir to the Eli Lilly pharmaceutical fortune, and a “minor poet.” In the 1980s, Lilly endowed annual prizes of $25,000, then $50,000. Frequent donations followed. Then in 2002, she left Poetry a gift — $200 million.

Today, the little magazine that T.S. Eliot called “an institution” has expanded far beyond its modest beginnings. Monthly issues continue, now issued from a North Chicago office with a library of 30,000 books and a wonderful website.

“To have great poets,” Walt Whitman observed, “there must be great audiences too.” To foster great audiences, Poetryfoundation.org features works from 5,286 poets, plus online book clubs, tutorials, videos, podcasts, a Poem of the Day, and Poem Guides, short essays each explaining a single poem.

Crusty Easterners still scoff. A Children’s Poet Laureate? A high school Poetry Out Loud contest? “The foundation seems to want to promote poetry, the way you’d promote cereal or a sitcom,” sniffed the Yale Review.

William Carlos Williams disagrees. Poetry, the modernist old doctor noted, is where you find it. And unless you find it. . .

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.