THE KINDLY CAREER OF WAVY GRAVY

BETHEL WOODS, NY, AUGUST 1969 — From the stage to the sweeping hillside, the horizon is people, seas of people. As the sun comes up, a gravely voice welcomes the throng to another day of Woodstock.

“Good morning! What we have in mind is breakfast in bed for four hundred thousand.“ Dressed in jeans and a floppy farmer’s hat, the speaker mentions the Hog Farm, his commune, but gives no name. Why?

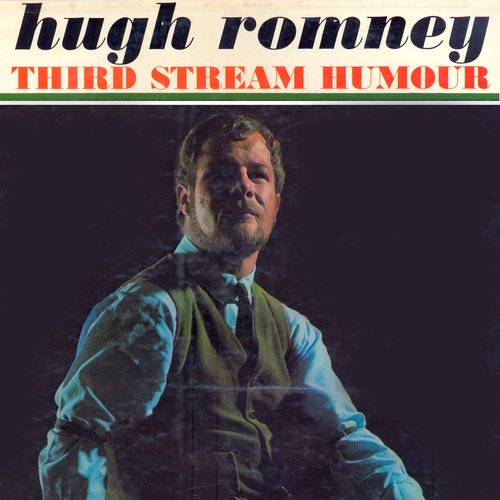

Because when compared to Hendrix, Joan Baez, Janis Joplin, etc., who was Hugh Romney? Only later, under a new name, did he become synonymous with the Sixties.

Wavy Gravy is. . . a comedian, a clown, a Merry Prankster, a Ben & Jerry’s ice cream flavor. But in five decades since Woodstock, he has also been, wrote the Village Voice, “one of the better people on earth.”

At 87, Wavy Gravy remains “an authentic unreconstructed hippie idealist living the communal life, doing good works and advocating peace, love, and laughter, in the guise of a clown.”

Clowns usually stop at laughter, but Gravy (get used to it) has spread his joy in a lifetime of humanitarianism. And the world, as if enjoying breakfast in bed for 7 billion, is a better place.

Little is known about his childhood. The son of an architect, Hugh Romney started out on a traditional road. High school in West Hartford, CT, the army, then Boston University, studying theater.

But the counterculture was rising and Romney was on its cutting edge. Moving to Greenwich Village in 1958, he began reading his poetry at the Gaslight. Within months, he was booking the fabled club’s entertainment. Dave Van Ronk. Peter Paul and Mary. And one guy, who became his roommate, named Dylan.

Romney turned to comedy, making up wild stories onstage. He joked about being addicted to time. Like all addictions, it started small — with seconds, but he was soon hooked on minutes, then entire hours!

“Everybody says, do you make that stuff up yourself and I say ‘yeah,’ but it’s a lie because I have these movies on the inside of my brain.” In 1962, Lenny Bruce brought Romney to San Francisco where he joined the improv troupe, The Committee. But he was too “far out” for them, once doing a two-hour show in a “meat suit” patched together from hunks of steak.

Romney’s life changed when he and his wife, a rising actress, were evicted from their San Fernando Valley apartment. Seems they were hosting a dozen of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters whose dayglo bus Romney had ridden “Further,” from coast-to-coast.

Romney soon learned of a hog farm on a nearby hillside. In 1966, while teaching improv to actors, he and Bonnie started one of the first Sixties communes. Two years later, the Hog Farm toured America in psychedelic buses “calling upon all earth people to join us in celebration, and all you need is yourself.”

Peace. Love. Understanding. Crazy stuff in ‘68 but the following summer, a friend invited the Hog Farm to help at Woodstock. Put in charge of security, Romney called his group the “please force,” because they asked people to please do this, please not do that.

Later that year, at a Texas blues festival, Romney got a new name. "They had these conga drummers on stage,” he recalled, “and I said, 'Don't dance on the wavy gravy'.” BB King soon approached. “He said, 'Are you Wavy Gravy?' and I just said, 'Yes, sir,' The name has worked pretty well throughout my life. Except with telephone operators I have to say 'Gravy, first initial W.'"

After Woodstock, Gravy expanded his good cheer. In 1970, learning of a massive flood in Bangladesh, he led a caravan of buses from Paris to Dacca, bringing food and medicine. “We would embarrass these governments. They said, ‘My God, there’s hippies doing it, we gotta do it better.’”

What he saw of the world made even a clown pause, but not for long. In 1975, he founded Camp Winnarainbow to teach circus arts to kids. Then came the Seva Foundation (from the Sanskrit word for “selfless service to others.)

With money from benefit concerts featuring his friends — the Grateful Dead, Bonnie Raitt, Elvis Costello, etc. — Seva started health projects from China to India to Guatemala. Most of the money went to cataract operations that restored sight to some three million people. Wherever Seva went, Wavy Gravy followed, clowning for kids.

Which is why Sixties satirist Paul Krassner called his friend “the illegitimate son of Harpo Marx and Mother Teresa.”

On into the new century, Wavy Gravy kept up his spirits. Beaten by police during anti-war protests, his bad back led to operations and chronic pain. But put a red rubber button on his nose and he was off again to tickle and transform the world.

“Laughter is like the valve on the pressure cooker,” he says. “If you don’t laugh, you’re gonna end up with beans on the ceiling.”

The former Hugh Romney still lives on the Hog Farm in Berkeley, with his wife of 48 years who often calls him Saint Misbehavin’. He has hosted podcasts, performed at hospitals and nightclubs, and resurfaced at Woodstock anniversary concerts. And he has retained the blithe spirit first heard before breakfast in bed. His words back then proved prophetic for a life of unapologetic joy.

“It’s gonna be good food and we’re gonna get it to you,” he graveled to the crowd. “We’re all feeding each other! We must be in heaven, man! There is always a little bit of heaven in a disaster area.”