VIEQUES RISING

VIEQUES, PUERTO RICO — JANUARY 1979 — The fishermen never wanted a battle. They just wanted to ply the waters off their island, hauling in lobster, snapper, and perch. Then a U.S. Navy training exercise banned fishing for 28 days. Fishermen met with officers, pleading for the chance to earn their living. An admiral told them to apply for food stamps. The Battle of Bahia de la Chiva was on.

That Sunday, an admiral told a fisherman,2,500 Marines, backed by helicopters, gunships, and landing craft, would hit the beach. “You don’t know my people,” the fisherman told the admiral. “You are going to have problems.”

Eight miles off the eastern tip of Puerto Rico lies a Caribbean island like few others. The beaches of Vieques are idyllic, and the island’s two small towns have the usual Margaritaville — bars, restaurants, rum drinks. But Vieques has no high rise hotels, no huge resorts, no teeming tourist trade. Horses roam freely. Its bioluminescent bay, wrote Lonely Planet, is “nothing short of psychedelic.”

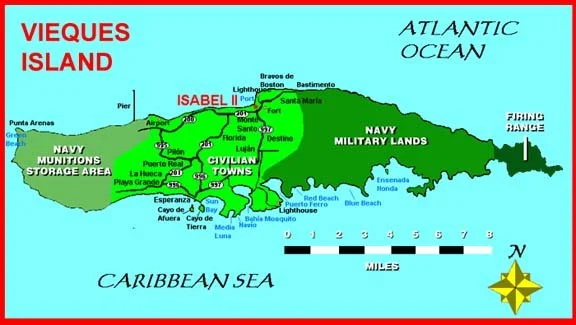

Paradise, perhaps. But two-thirds of Vieques remains off limits, a testament to a troubled history that, twenty-some years ago, had a happy ending.

Vieques was always an outlier. Even after Columbus and Ponce de Leon landed here and wiped out native Tainos, what locals now call La Isla Nena (“little girl island”) remained up for grabs.

Over the next few centuries, Vieques was claimed by the British, the French, the Dutch, and assorted pirates. When the Spanish finally took over, cane plantations thrived. Then in 1898, Puerto Rico fell under U.S. rule. And with World War II, a new U.S. Navy base on “the big island” annexed both ends of Vieques. After the war, the bombing began.

For half of each year, some 80 bombs a day blasted the eastern tip of Vieques. Windows rattled. Planes roared. Ammunitions, including napalm and depleted uranium, were stored on the island’s west side.

On a strip of land between Navy territory, some 9,000 Viequenses eked out a living. Resentment festered until the fishermen sparked a movement. It began with nets.

One morning in 1977, fishermen rowed out to haul up their wood and chicken-wire traps, known as nasas. The lines of 131 traps had been cut by Navy propellers. When fishermen sued, the Navy had the case transferred to Virginia, forcing fishermen to travel and stay in motels there. The judge lambasted the Navy and ordered reimbursement for traps and travel.

“We have a greater right to be here than the Navy does,” said Carlos Zenon, leader of the Fishermen’s Association. “We got here first.” The lucha had begun.

January 20, 1979: As 2,500 Marines prepare to land, eighteen open wooden boats leave the harbor in Esperanza and head for Bahia de la Chiva. Two fishermen per boat, they bear down on warships bobbing in the bay. As Marines climb into landing craft, the boats approach.

Collisions seem unavoidable, but at the last second the small boats swerve around each landing craft. Fishermen throw buoys, attached to chains, into the water, then circle each craft, tighter, tighter. When the landing craft head for shore, chains lock around their propellers. The Marines are dead in the water. No one will land on the beach that day.

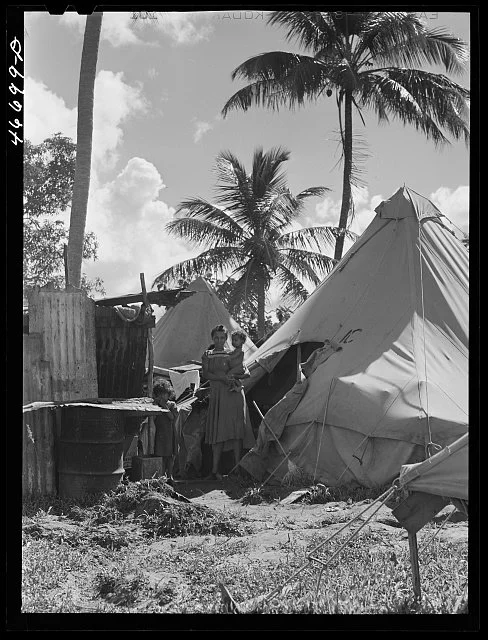

For the next year, fishermen and the Navy played similar games of chicken. Daily bombing continued and resentment deepened. Then in April 1999, two bombs from an F-18 missed their targets. A Viequense security guard was killed. Within days, locals invaded the bombing grounds. On gorgeous beaches littered with artillery shells, tent cities hunkered down.

For the next two years, protest raged. The Navy suspended bombing. Camps were cleared out. The Senate held hearings. The Navy resumed bombing. Signs proclaiming “No Mas Bombas” sprouted across the island. Celebrities and activists came to join peaceful protests. Some 1,500 were arrested and many spent a month in jail.

“We’ve never felt anything like this before,” said Martina Rodriguez. 'This is the Vietnam of my generation.”

A referendum on Vieques was planned but before votes were cast, President George W. Bush intervened. On May 3, 2003, Bush announced, the Navy would leave Vieques. A two-year countdown began.

Because Puerto Rico needs no excuse to party, the celebration began early. For days before the deadline, there was dancing, music, fireworks. On May 2, Puerto Rican Governor Sisa Calderon arrived. “This is a moment of great happiness and profound emotion,'' she told crowds when the music finally died down. “Together, we achieved the end of the bombing.''

Vieques lives with its legacy as a bombing range. Cancer rates are disturbingly high. Former Navy grounds are a Superfund site, but the cleanup drags on. Yet palm beaches are quiet now. Windows do not rattle. Horses graze and meander on. “The entire island feels a bit untamed,” noted Let’s Go Puerto Rico.

And Vieques’ main attraction, the world’s brightest bioluminescent bay, is brilliant again. Reach over the edge of your kayak. Run a hand through the water and watch the sparkles flow. Like stars, like fireflies, like hope.

When she came here in 1963, Maria Velazquez told the New York Times on Liberation Day, her husband said, “‘Viéques needs people who love the land to rescue it.’ We've been rescuing it ever since. I feel like I'm walking on air.”