DOWN THOSE SESAME STREETS

MANHATTAN, NOVEMBER 1966 — Another morning on “the boob tube.”

Porky Pig, Atom Ant, Secret Squirrel. . .

Five years have passed since the FCC chairman called TV “a vast wasteland.” Noting that children “spend as much time watching television as they do in the schoolroom,” Newton Minow asked, “Is there no room on television to teach, to inform, to uplift, to stretch, to enlarge the capacities of our children?”

Magilla Gorilla. Hoppity Hooper. Heckle and Jeckle. . . Apparently not.

That Saturday evening, TV’s only female producer hosted a dinner. Guests included an executive at the Carnegie Corporation. Over cocktails, the Carnegie man asked, “Do you think television could be used to teach young children?"

"I don't know,” the hostess replied, “but I'd like to talk about it."

Joan Ganz Cooney’s “little dinner party” made her one of the most influential teachers in history. Because she soon took time off to study children. And education. And television. And how the three might mix.

“Children all over the country were singing commercials,” she recalled, “so they were certainly learning something from television. The question was not whether it could teach but could it teach something of potential use.”

Growing up in Phoenix, Joan Ganz was “raised to be a housewife and a mother, to work an interesting job when I got out of college, and to marry at the appropriate age, which would have been twenty-five.” Cooney started down that road but a priest sent her elsewhere. In 1953, TV was in its infancy, but many were already worried. Was “Howdy Doody” the best Kid TV could offer?

“Father Keller said that if idealists didn't go into the media, non-idealists would." After a stint as a journalist, Cooney moved to Manhattan and began talking herself into television. By day, she wrote publicity for mindless shows. By night, she worried. “I was plagued in my 20s that I was going to die without making a difference. And I think when I heard of educational television, I thought I could make a difference there.”

Applying as a publicist at WNDT (later WNET), she was told they only needed producers. “I can produce!” she said, though she had no experience. She was hired. She later recalled, "I've never been qualified for any job I've been hired for."

Cooney soon produced documentaries on Cuba, on poverty, but most educational TV was a classroom with a camera on it. Then she hosted her “little dinner party” and took a leave of absence.

After months of research, Cooney handed the Carnegie Foundation a 55-page paper. "The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education” was not another dry policy paper. Cooney had the blueprint for a revolution, televised.

“We wanted to show an integrated street, we wanted to show adults treating each other kindly, and we wanted the adults to be forceful and dignified.”

And she wanted a show as fast, as fun as TV’s top show, “Laugh-in.” “Kids like commercials and banana peel humor and avant-garde video and audio techniques. We have to infuse our content into forms children find accessible.”

Throughout 1968, Cooney assembled her team. Writers and song-writers jousted with buttoned-down TV executives. Cooney’s new Children’s Television Workshop held seminars on pre-school education. At one seminar, she met a genius.

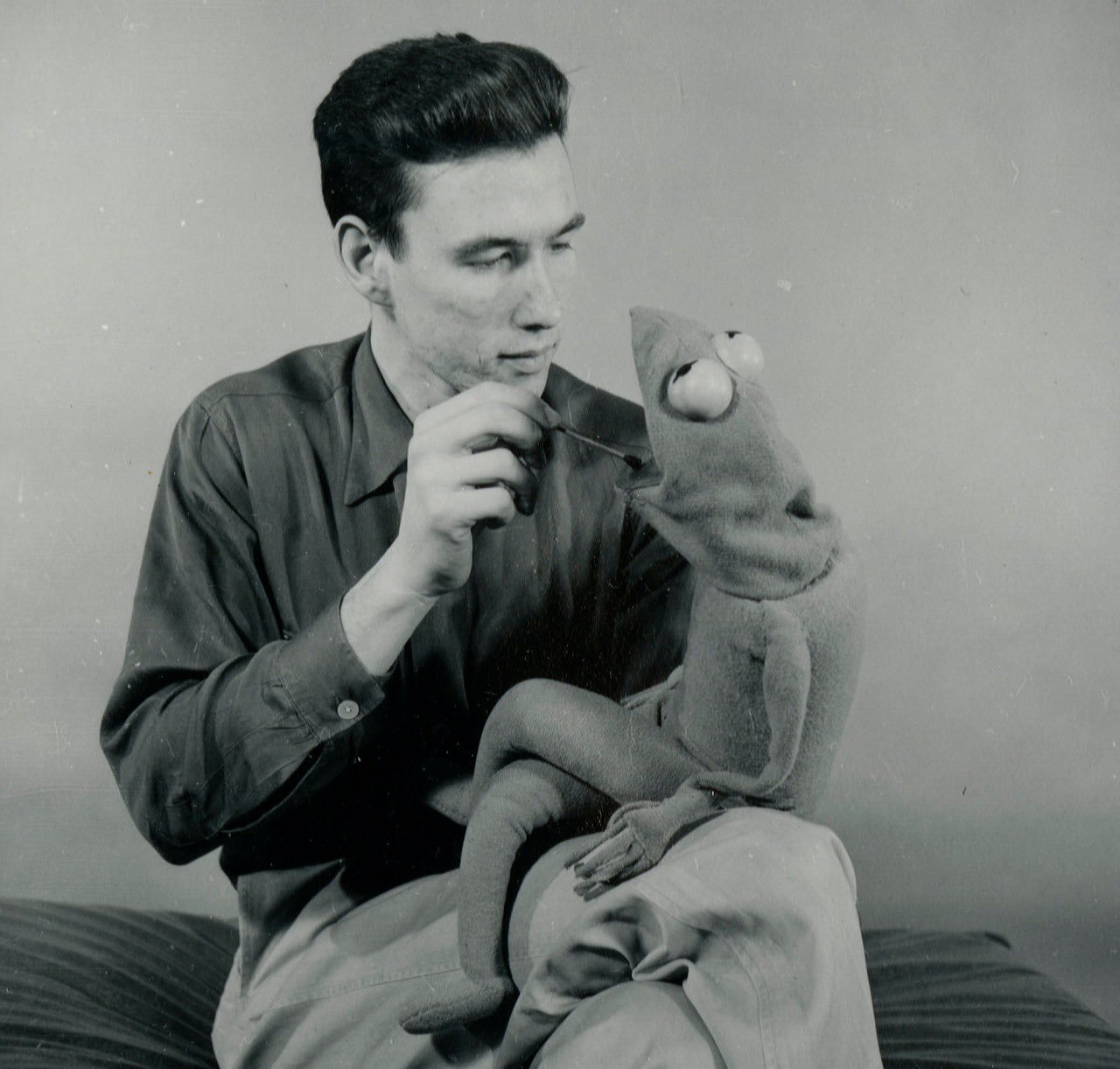

“There was a kind of collective genius about the core group that created ‘Sesame Street,’” Cooney said, “but there was only one real genius in our midst, and that was Jim.”

Jim Henson’s merry band of Muppets had made a modest name on variety shows. Cooney knew them from commercials. “I couldn’t believe puppets could be so hip and funny.” But when Cooney approached him, Henson hesitated. The Muppets were “adult puppetry.” Yet as a father of four, he found something in this new show and its whipsmart producer. Cooney soon convinced Henson to join the team.

On into 1969, the work continued. Drafts. Dead ends. Pilots screened before pre-schoolers. When test-audience toddlers tuned into the Muppets but lost interest in live characters, the Muppets were put front and center. Henson, however, needed more merriness.

How about two guys, best friends, one vertical, the other horizontal? And a big doofus bird? And lest the show seem “too sweet,” perhaps a grouch? When Cooney had the brilliant idea of turning numbers and letters into commercial “inserts,” the Muppets had even more fun. By the fall of 1969, everything was set except the name.

“123 Avenue B?” “Fun Street?” “ The Video Classroom?” Finally a writer suggested "Sesame Street.” The director thought it “awful,” but no one had anything better. On November 10, 1969, “Sesame Street” debuted. The reaction surprised the whole team.

“This was an educational children’s show,” Henson’s assistant said. “The thought was ‘thirteen weeks and it’ll be over.’” Even Cooney was shocked. "The reception was so incredible. The press adored us; the parents adored us."

Variety called Cooney “Saint Joan.” Talk shows introduced her as “the woman responsible for what may be the most important advance in the history of our business.” A dozen colleges gave her honorary degrees. And “Sesame Street” spread worldwide.

By 1970, the show aired in 50 countries. Back in American living rooms, some 7 million kids knew “how to get to Sesame Street.” A seed had been sown in the wasteland. Children’s Television Workshop soon produced “The Electric Company” and “3–2-1- Contact.” And TV, taught by “Sesame Street” that children have brains, responded with smart shows from “Magic School Bus” to “Reading Rainbow” to Bill Nye.

Fifty-some years and ninety-some Emmys later, “Sesame Street” is going strong. So, at 94, is Joan Ganz Cooney. Though she retired from CTW in 1990, she remains active in boardrooms and in TV. Since 2007, the Joan Ganz Cooney Center has studied how to improve digital media for pre-schoolers.

Given every award from Urban League honors to the Presidential Medal of Freedom, even her own Muppet model, Cooney insists that “Sesame Street” was always a team effort. And though “brought to you by the letters A and E and. . .” it was always something more.

“The aim of the show is really to foster mutual respect for one another," she says. "The show is about warmth and human understanding."