PROJECT 562 -- REBIRTH OF NATIONS

SMITH RIVER, CA — FALL 2012 — On the edge of this native nation of 120 people, along the foggy, windswept Oregon border, the Tribal Council assembles. Today’s guest is from the Tulalip nation. She wants permission to take photos.

Matika Wilbur has no slides, no outline. “I didn’t even have an elevator pitch.” But she has gifts — homemade peach jam and freshly smoked salmon. The gifts work their ancient magic.

“The Tolowa Dee-ni’ people were kind to me,” Wilbur recalled. “Maybe they even pitied me; nonetheless, they fed me, prayed with me, let me photograph them, and shared their personal stories.”

One nation done, 561 to go.

In 2012, the U.S. government formally recognized 562 native nations. Beyond the better-known Navajo, Hopi, and Cherokee lay a patchwork of peoples, bloodied but unbowed. Once a year we remember them on “the other Columbus Day,” aka Indigenous Peoples Day.

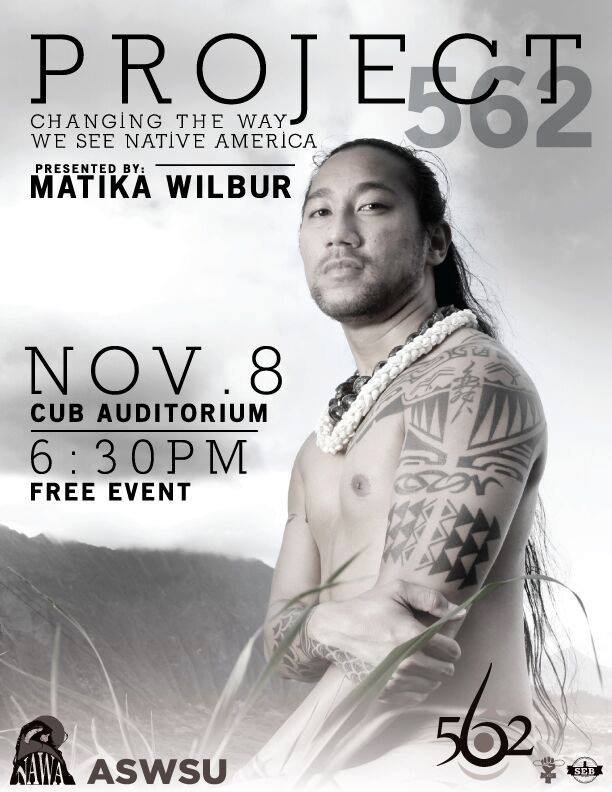

But Matika Wilbur has spent the last decade remembering, honoring, and photographing all 562 nations. Her Project 562 is “a love letter to indigenous Americans,” Forbes wrote. The book is also an antidote to tired stereotypes.

“The way Native people see ourselves affects the way we treat ourselves,” Wilbur says.

She learned that lesson the hard way. Wilbur grew up in a Tulalip-Swinomish family waging the common native battle between pride and poverty. After studying photography, she recoiled from commercial work and returned to her native Washington to teach high school.

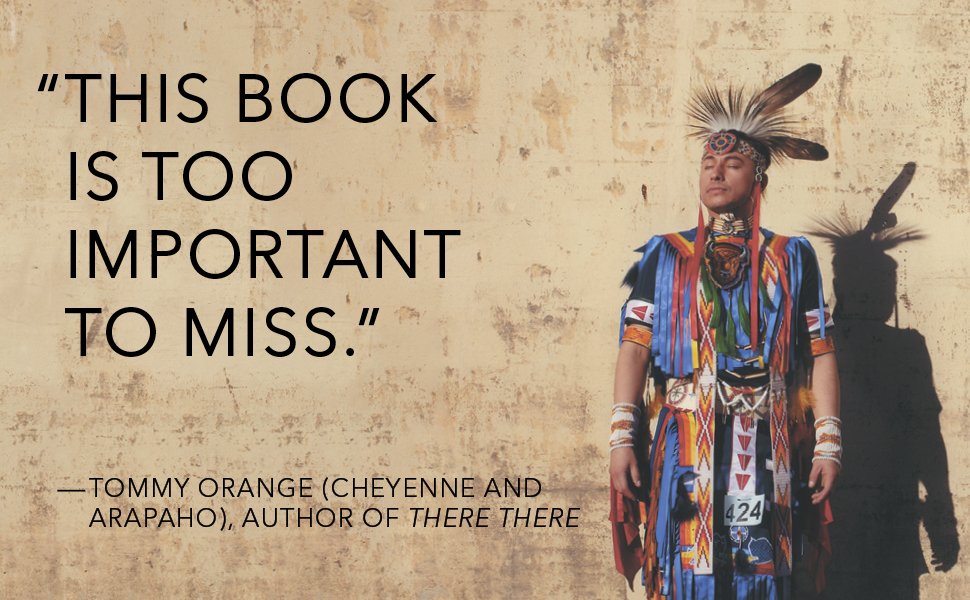

But when a student asked her to skim the Internet for images of natives, Wilbur was appalled. “When you Googled ‘Native person, Native American,’ what you found was a leather and feathered person.” Though Native-Americans are in resurgence, these Hollywood images — of warriors, chiefs, and “squaws” — have never been put to rest.

Wilbur, then 28, vowed to change all that. In the fall of 2012, using funds from a Kickstarter campaign, she sold everything in her Seattle apartment and hit the road. Her goal: visit all 562 nations and bring back the photos and stories.

She thought the project would take three years, but it soon turned into “a soul baring labor of love.” “I might as well have called it ‘Project Forever’.”

For the next decade, Wilbur drove the RV she nicknamed “Big Girl” through all 50 states. Unlike Edward S. Curtis, the legendary “shadow catcher” who posed natives as he saw fit, Wilbur allowed her subjects to be themselves, dressing, posing, and choosing their own backdrops.

Project 562 is the remarkable result. Here are natives you will never see onscreen, men, women, and children, some using native names — Raven and Free Eagle — others with names that give no clue to their heritage. Gail Small (Northern Cheyenne), Rupert Steele (Shoshone), Kathy Jefferson (Lone Pine Paiute).

On reservations, in cities and small towns, in canyons and other wild places, Wilbur became both eyes and ears. Though her native name means “woman who teaches children,” she became a student at the feet of elders, a seeker of timeless tribal wisdom.

The 562 nations she visited were as distinctive as any peoples on earth, but all welcomed her with warmth and humor. “Through it all, there was so much laughter. Indian humor is the best medicine.”

Among the artists, musicians, teachers, and others, certain subjects stood out. In San Francisco, Wilbur spoke with John Trudell, leader of the 1969 Indian occupation of Alcatraz. Trudell, then dying of cancer, advised her to seek not just native perspectives but a broader version of humanity as seen through native eyes.

“Race and gender have been turned into victim identities,” Trudell told her. “And once you participate in reality based on your victim identity, you no longer recognize your own connection to power.”

On her “labor of love,” Wilbur melted into hot springs in Utah as the sun rose over red mountains. She swam in the Grand Canyon, harvested wild rice, saw the lime green curtains of the Northern Lights. She sat in condos and tipis, apartments and hogans.

Tapping the experience of whole nations, she visited the Akwesasne Freedom School in upstate New York. She trekked to 14,000 feet on the annual Indigenous Women’s Hike through the Sierras. She paddled with hundreds of other canoes through Puget Sound, and visited Native women’s shelters from coast to coast.

In every nation, she saw “a collective fire burning inside the hearts of indigenous people, and that fire wants the truth.”

Now 38, with her own family and nation to nurture, Wilbur is back home in Seattle. She can barely believe her project is finished.

“I wonder if it was all a dream. How did I manage to visit every state, log six hundred thousand road miles, and survive vehicle crashes, an RV on fire, blizzards, tornadoes, loneliness, sorrow, heartbreak, and long treacherous journeys from the Bering Sea to the Everglades? It was and is the people. Their stories. Their kindness.”

The federal government now recognizes 574 native nations. A century ago, their population was just a quarter million. Now they have grown to 5 million. Pride still battles poverty, but Project 562 takes America beyond its stupefying stereotypes. Google “Native Person, Native American” now and many of the images that come up are from Project 562.

The resurgence continues. “It all comes back to how do we re-member a people?” L Frank Manriquez of the Tongva Nation told Wilbur. “Not remember, but re-member something that has been dismembered. Incredible things happen when we start being who we fully are.”