CHILDHOOD BEYOND THE BLUE

CORNISH, VT — On icy winter days, in late afternoon, an unearthly blue appears over soaring Mt. Ascutney. The blue is deeper than any ocean, airier than any cloud.

Suggestive of infinite twilight, the blue opens a window into some private Arcadia. And for more than a century, this cobalt color graced prints and calendars in living rooms, dens, and especially college dorms.

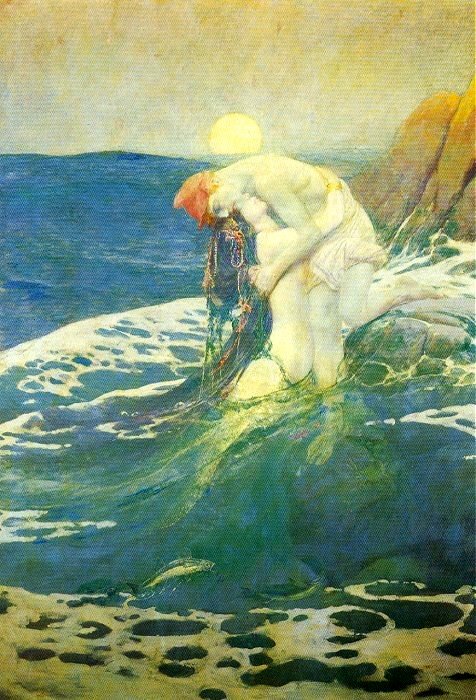

"Oh, they're a-hangin' Maxfield Parrish in the village," rang a campus ballad in the 1920s. And in prints hung on dorm walls across America, that certain blue framed lone women perched on rocks and draped in diaphanous gowns.

Between the World Wars, Maxfield Parrish was the commoner's Rembrandt. A Parrish print in a store window drew crowds. His dreamscapes hung in hotel lobbies. Housewives bought his calendars, cut off the dates, and framed each page.

In a world where skies were too often gray, Parrish painted the stuff dreams are made of. At the height of his career, a Parrish print hung in one of every four American homes.

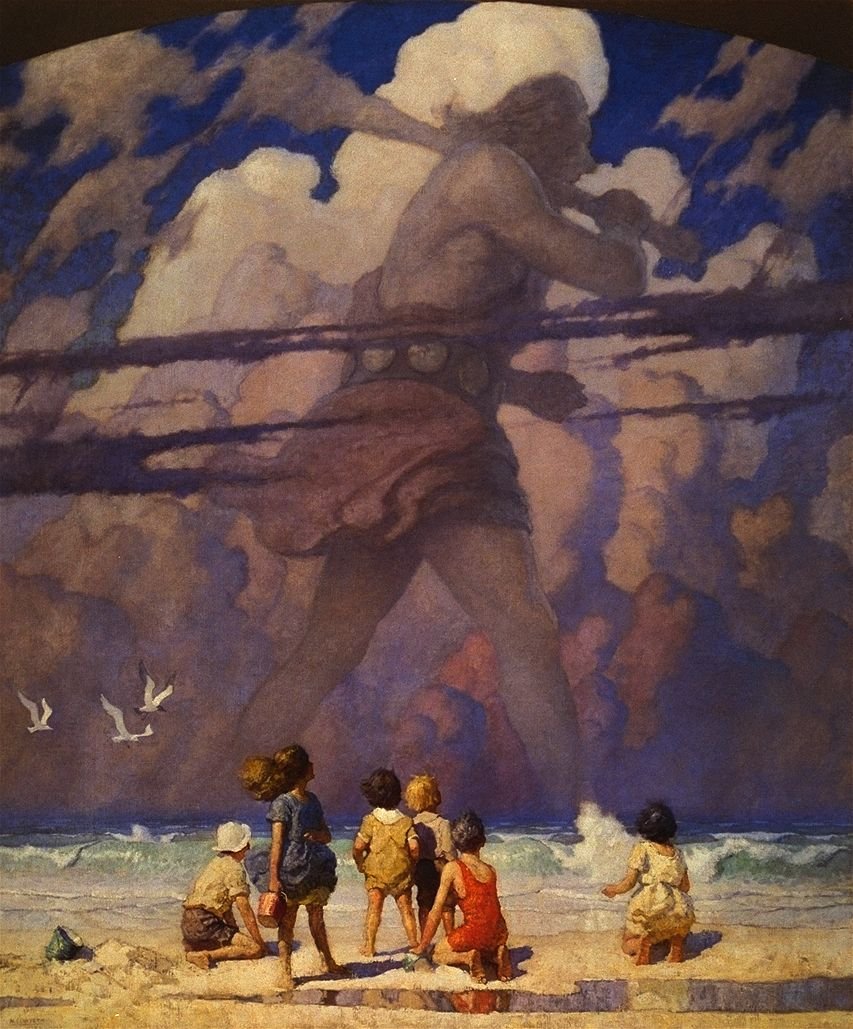

Parrish’s imagery still sells on postcards, screen savers, mousepads, tote bags, calendars. . . But his “girls on rocks,” which critics dismissed as "sentimental gushings," have hidden the worlds of wonder Parrish made for children. He learned the art by being a child himself.

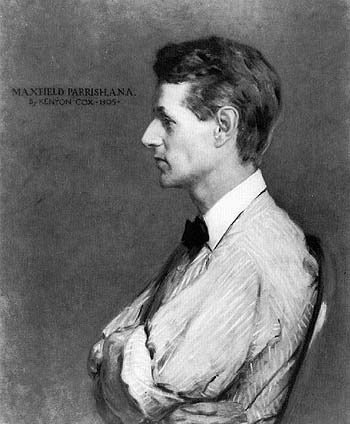

As a boy in Philadelphia, Parrish sketched dragons, genies, and goblins. His doodles were simply delightful. His artistic chemistry -- one part imagination, one part wit -- soon led Parrish to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where he was hailed as “one of the most brilliant and most suggestive decorative painters in the country.” He was all of 22. Reviewing Parrish's work, Howard Pyle, the nation's leading illustrator, said there was nothing more he could show the young artist.

Quickly in demand, Parrish decorated restaurant menus, magazine covers, ads for baking powder and bicycles. In all this early work, his inner mirth bubbles to the surface.

A short, puckish man with a wild shock of hair and piercing eyes – blue, of course -- Parrish was as charming in person as in print. Quick with a quip, he was the delight of neighbors and children. Well into his 90s, he kept a twinkle in his spirit. Learning that his old letters were being sold, he noted, "I dare say they thought I was dead, and they may be right. I must look into that." The same impish humor abounds in his children’s books.

The turn of the 20th century was the golden age of children's’ illustration. And the most golden were (left to right above) Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, and Maxfield Parrish. Cut from a child’s coat of wonder, Parrish’s art enhanced Kenneth Grahame’s Dream Days.

His Humpty Dumpty enlivened Mother Goose in Prose by the author who later took us to Oz, L. Frank Baum.

And in a hint of cliches to come, his euphoric “Dinkey Bird” sent a woman soaring on a swing before a castle in the clouds.

“His whimsical notions,” the New York Times wrote, “are alive with more imaginative fire that any child could kindle. In fact, his interpretations are so successful because they seem to take the child's point of view in their sparkling innocence and ingenuity.”

Yet as art went modern, as children like himself grew up, Parrish became “a businessman with a brush.” During the 1920s, Parrish began painting dreamscapes for adults. Posing the young model who became his mistress, he satisfied a seemingly insatiable demand for blue-tinted idylls. Picasso had a blue period — Parrish had a blue rut.

Rather than renounce the income that let him live on his Vermont hilltop, he painted paradise ad nauseam. Throughout the 1920s, he was the highest paid illustrator in America. More than 17 million Maxfield Parrish calendars fed the public's hunger for his blend of the exotic and the erotic.

Finally, in the mid-1930s, Parrish renounced his cliches. ”I'm done with girls on rocks. I've painted them for thirteen years and I could paint them and sell them for thirteen more. . . It's an awful thing to get to be a rubber stamp.” He soon painted his last human figure. Then, still spry at 66, he rose each morning to paint what he wanted, mostly ethereal landscapes without a child, a girl, or any other human figure.

On through the age of abstracts, America forgot Maxfield Parrish. Yet when he died in 1966, at age 95, Parrish was "in" again. Critics hailed him as a pre-cursor of Pop Art. And as anyone who went to college in the 1960s recalls, they were hangin' Maxfield Parrish in dorms again. Norman Rockwell called Parrish “my idol.” Andy Warhol collected his work. Contemporary collectors include Jack Nicholson and that master of his own make believe, Star Wars creator George Lucas.

Parrish originals are now found in many museums, and “Parrish blue” is a cultural cliche. Yet only by stripping off the cliches can we recapture the child in the man.

"I get so excited and carried away with what I am doing that 'tis bad for one's nerves," he wrote his father early in his career. "There is in it at times a wild fiendish delight which partakes of all sorts of sensations, of what is possible in art and in me and in everything."