WHERE THE HEROES LIVE

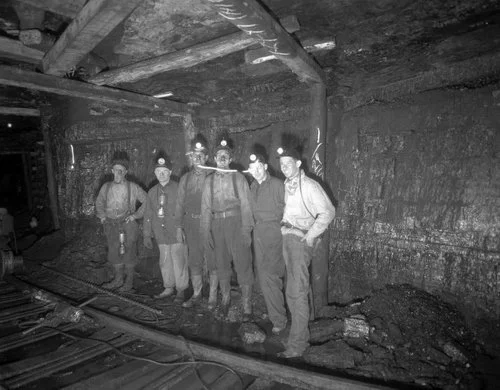

CHESWICK, PA — JANUARY 25, 1904 — All weekend, bitter cold gripped the Allegheny Valley. Coal families, mostly immigrants from Eastern Europe, shivered in makeshift shacks. Then on Monday morning, 180 men went down into the Harwick mine.

At 8:15 a.m., methane trapped in an ice-clogged ventilator shaft blasted the earth and blew coal into the sky. Men were buried in rubble, smothered in coal dust. All morning, bodies were hauled out, covered, stacked on frozen ground. There seemed to be no survivors, yet wives and children gathered, pleading, calling out names.

Mining engineer Selwyn Taylor came from Pittsburgh to help. After getting the ventilation fan running, Taylor and a rescue party went down. They found bodies, more bodies, but at the bottom of the shaft, a 17-year-old boy stirred. After getting him hauled to safety, Taylor went on. Overcome by gas, he turned back. He died the next day. Many other rescuers also scurried to the surface but Daniel Lyle went deeper, deeper, looking for survivors. He was never seen again.

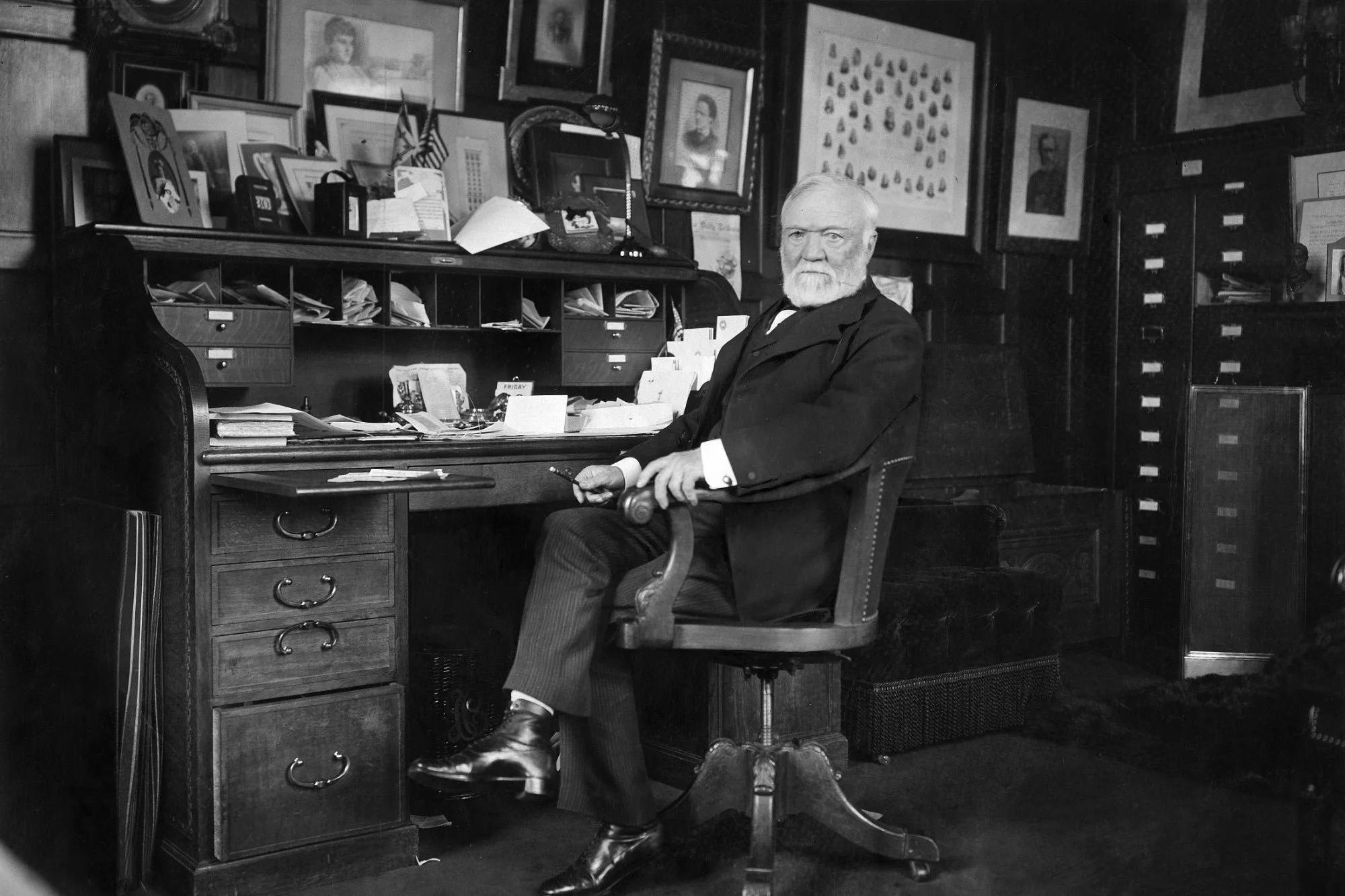

The Harwick Mine Disaster might have been just another sad story in American industrial history. Coal mining claimed 3,000 lives a year back then. But when news reached Andrew Carnegie in New York, he could not “get the women and children of the disaster out of my mind.”

Rising from telegrapher to tycoon, Carnegie was the world’s richest man. His ruthless treatment of labor made him notorious, but while other aging tycoons lived in luxury and left fortunes to families, Carnegie crafted a “gospel of wealth.” “The sole purpose of being rich is to give away money,” he wrote. “The man who dies rich thus dies disgraced.”

Within days, Carnegie doubled the rescue funds pouring into Pennsylvania. That spring, he endowed the Carnegie Hero Fund. Though less noted than Carnegie Hall, Carnegie-Mellon University and the 2,500 Carnegie libraries, the Hero Fund continues to honor Americans who “knowingly risk death or serious physical injury to an extraordinary degree while saving or attempting to save the life of another person.“

Knowing that “heroic action is impulsive,” Carnegie did not expect to inspire heroism. Yet heroes deserve recognition, he insisted, and their families deserve support.

Cynics take note. Since 1904, Carnegie’s fund has honored 10,300 heroes and awarded $40 million to their families. In its first decade, the fund found several heroes each year, including a black man in 1907, Native-Americans two years later. Ever since, whenever someone risks life to save life, the fund takes note.

The 9/11 heroes we remember this week were honored, of course, but most heroes do not make worldwide headlines. Consider:

Raemonda Freeman was at local baseball game in Pittsburgh when gang members chased a boy onto the field. Shots rang out. Others fled, but Freeman ran to the wounded boy and shielded him with her body. “He was just a kid,” she remembered, ”and I’m a mom, and I wasn’t gonna just leave him.”

Andy Johnson was driving home from work when he spotted a woman, an assailant, a meat cleaver. Johnson left his car, leapt on the man, disarmed him, and held him until police came.

“People always ask me why I did it,” Johnson said, “and I think that’s because they’re trying to figure out whether they would do it themselves.”

Six have won the fund’s medal twice. Daniel Stockwell was twenty when he saved a woman from drowning. Decades later, as a middle school principal, he entered a classroom held by an active shooter and offered himself in exchange for sixteen students. After all were freed, Stockwell stayed with the gunman, talking, until cops came.

Special people? Or do we all have it in us? Our instinct of fight or flight suggests it could go either way, yet those who did not flee insist they had no choice.

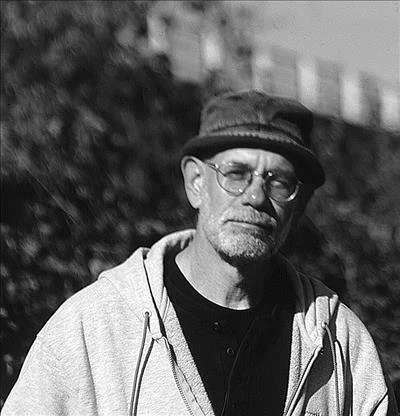

“As I approached the river,” Roger Olian remembered, “the overwhelming thing was that this was as desperate as a scene could be.” It was January in D.C. and a plane had plunged into the Potomac. Amidst strewn wreckage, people were freezing, floundering, going down.

“I was thinking that I have to try something and so I just kept running till I got to the edge of the river. And then I just hopped in. I could live with myself if I attempted to do something and failed. If I did nothing, I don’t know if I could live with that.”

“We live in a heroic age,” Carnegie noted in 1904. Yet our own age is no less heroic. Last year, the fund honored seventy-one heroes, this year, so far, another thirty-four. The latest roll calls include a 64-year-old Louisiana woman who dragged her patient from a wheelchair and out of a burning building, dying of smoke inhalation but saving the woman, and a father and son who rescued an elderly man from his burning home.

A hero, so the wisecrack goes, “ain’t nothin’ but a sandwich.” The Carnegie Hero Fund knows better.

Those honored, said former fund chairman Mark Laskow, often show “disbelief that what they did was so very special. But one of the nice things about the commission and the award is that we’re there to say, ‘Oh yes, it was special.’”

Roger Olian isn’t so sure.

“Everyone has the capability of doing extraordinary things under extraordinary circumstances. Even under circumstances that are not extraordinary, we all have the capability of helping each other. And we’re at our best when we do that.”