ROCKET SCIENCE FOR BEGINNERS

WORCESTER, MA — OCTOBER 19, 1899 — Afloat after reading H.G. Wells, a teenager climbs a tree and lifts his gaze. He sees nothing above but birds — and a dream.

“As I looked toward the fields at the east, I imagined how wonderful it would be to make some device which had even the possibility of ascending to Mars.” Such a “device” would soar up, up, beyond the atmosphere, toward the stars. “I was a different boy when I descended the tree from when I ascended. Existence at last seemed very purposive.”

Astronauts are too much with us now. Billionaire cowboys take quick trips into space. Jokers quip “It’s not rocket science.” But less than a lifetime ago, space was, as JFK said, “this new ocean.” The ocean’s explorers became household names. Armstrong and Aldrin. Sally Ride and Christa McAuliffe. But all would have been grounded if not for that boy in the tree.

“Don't you know about your own rocket pioneer?” Wernher von Braun asked the Americans who asked him about Nazi V-2 rockets. “Dr. Goddard was ahead of us all.”

Robert Goddard rose from a sickly childhood to heights unimaginable in his youth. In the 1890s, space travel was sci-fi. Journey to the moon? Absurd. But Goddard would never settle for the sky.

A Ph.D. in physics took him to Princeton but tuberculosis brought him back to Worcester. Bed-ridden, Goddard mapped out his dreams, with equations, in cloth-bound books.

Like Leonardo’s notebooks, Goddard’s contained visions of an age to come. If gunpowder did not have enough kick to defy gravity, why not try liquid fuel — liquid oxygen mixed with gasoline? If enough fuel wouldn’t fit in one chamber, perhaps multi-stage rockets. . . Might a rocket carry a camera. . . And if bringing the camera back to earth created enormous friction, perhaps a heat shield. . .

As TB tightened its grip, Goddard doubled down on living “in order to do this work.” By 1915, fully recovered, he returned to his alma mater, Clark University, to teach. In his spare time, he lit fuses.

One spring evening, a janitor saw a raging flame outside Clark’s physics building. Rushing to the scene, the janitor found a smoking tube, smoldering ashes, and a balding professor. From then on, Goddard did his tests in a lab. His calculations were correct. Solid fuel wasted 98% of its energy in heat and light. But liquid fuel couldn’t be perfected until liquid hydrogen was made. That breakthrough changed everything.

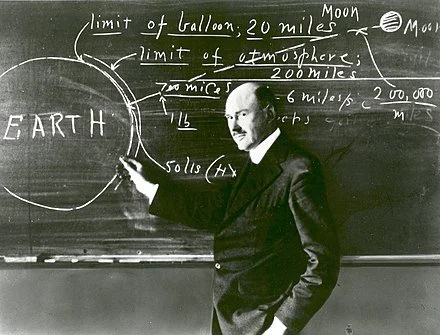

By then, Goddard’s “A Method for Reaching Extreme Altitudes,” had spawned curiosity and ridicule. “Believes Rocket Can Reach Moon,” read a 1920 New York Times headline. The article granted "the possibility of sending recording apparatus to moderate and extreme altitudes within the Earth's atmosphere.” But this man Goddard was not just reaching for the sky. He was reaching for the moon.

Read your Newton, the Times cautioned. Without gravity to push against, no thrust would move anything in outer space. “To claim that it would is to deny a fundamental law of dynamics. . . Of course, Goddard only seems to lack the knowledge ladled out daily in high schools.”

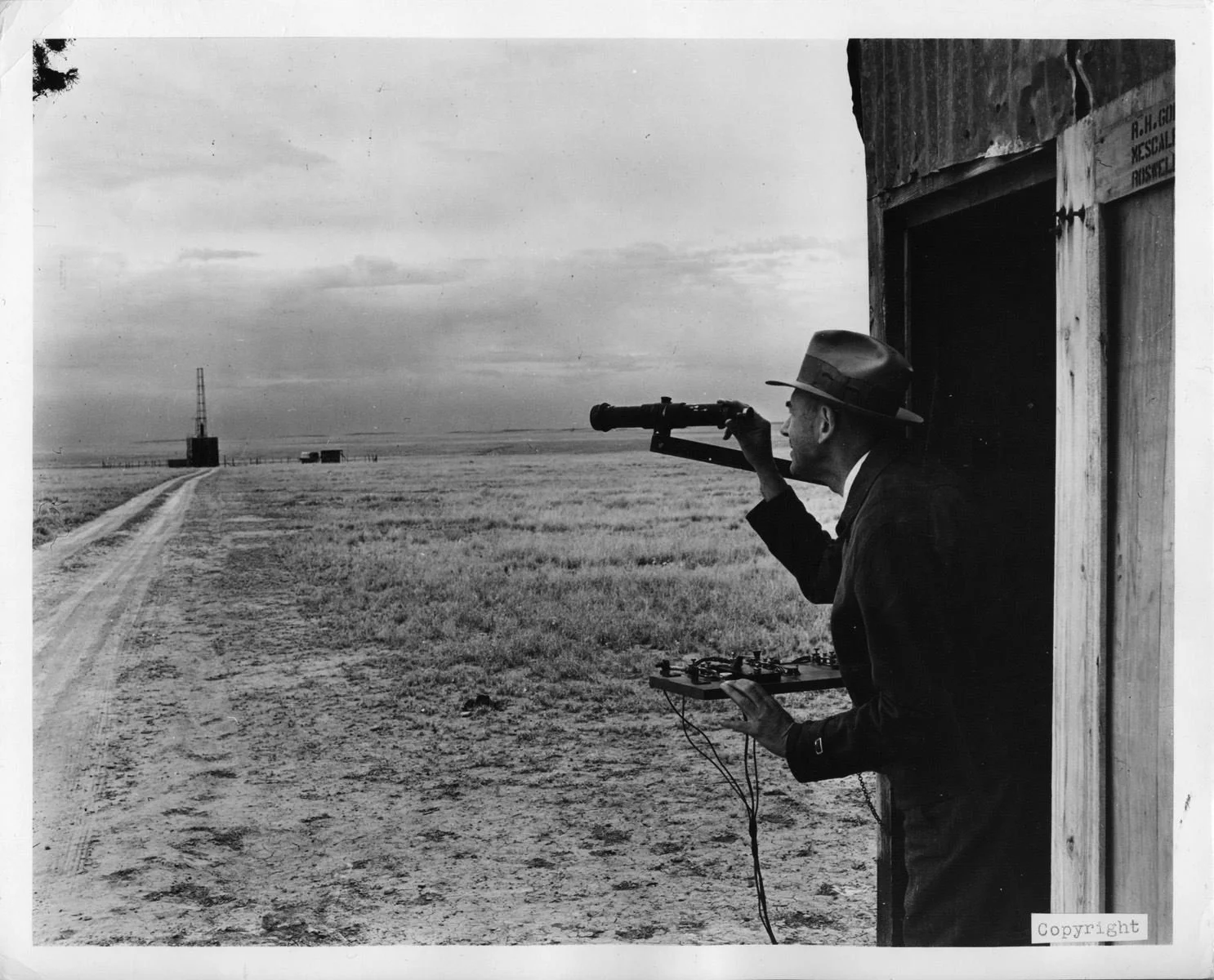

As the 1920s roared on, Goddard, working in his lab to perfect his rockets, shunned further publicity. Finally, on March 16, 1926, on a frozen lake near Worcester. . .

“The first flight with a rocket using liquid propellants was made yesterday at Aunt Effie's farm in Auburn. Even though the release was pulled, the rocket did not rise at first, but the flame came out, and there was a steady roar. After a number of seconds it rose, slowly until it cleared the frame, and then at express train speed, curving over to the left. . .”

Nicknamed Nell, this first rocket rose 41 feet, flew for 2.5 seconds, then crashed in a cabbage field. But it showed that liquid fuel worked and that gyroscopic guidance — another Goddard invention — could steer a rocket. The sky was no longer the limit.

Over the next fifteen years, Goddard launched 41 rockets. Some soared to 9,000 feet at almost 600 mph. Nothing had ever flown so high, so fast. The press mocked on.

Moon Rocket Misses Target by 238,799 1/2 Miles.

When Goddard died in 1945, his wife began reading his notebooks. What she found earned Goddard another 131 patents, bringing his total to 214. Nearly every device would be used by NASA which, in 1959, named its first flight center after Goddard. But others also remembered.

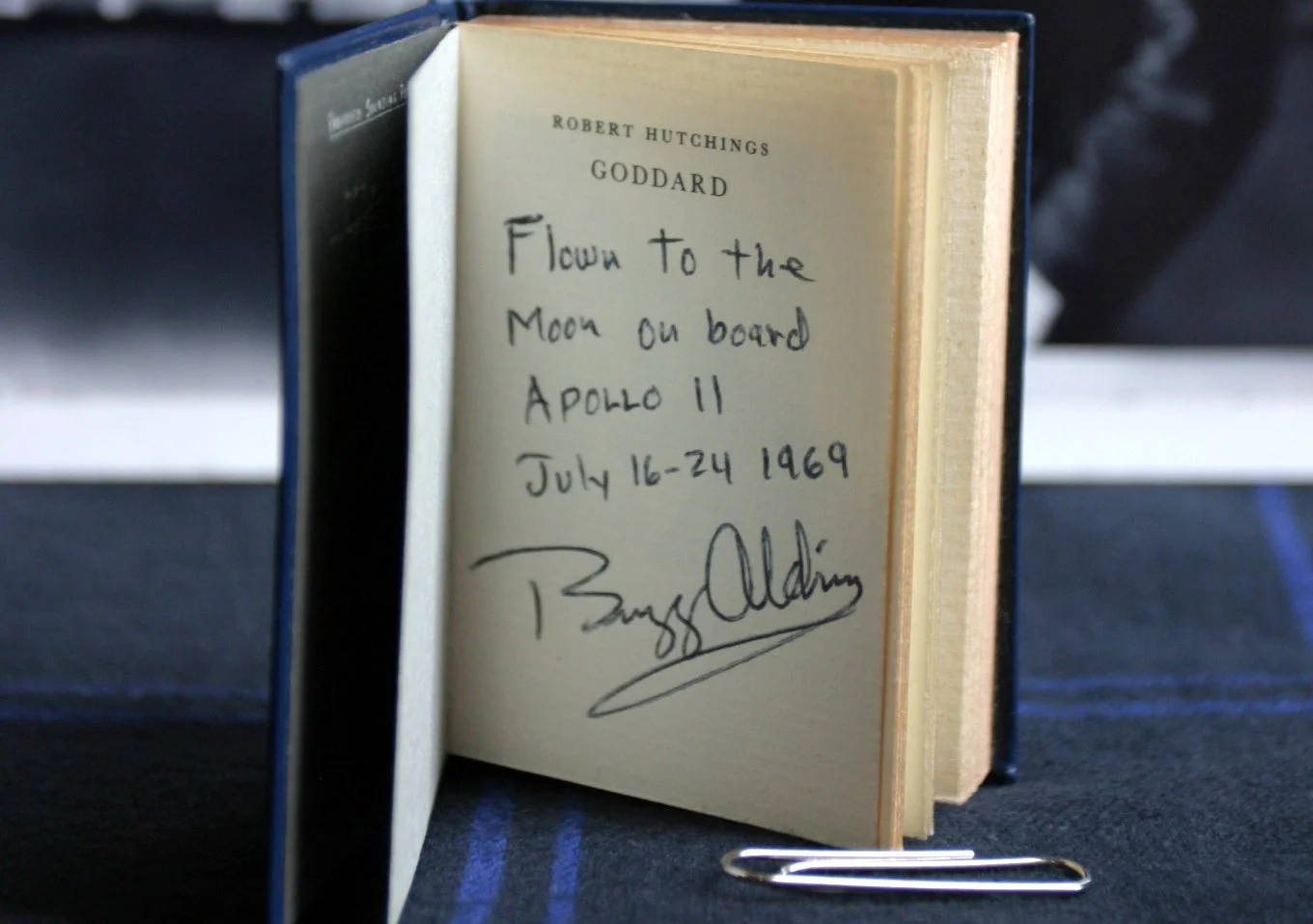

One of Goddard’s students at Clark was Edwin Aldrin, Sr. His son was nicknamed “Buzz.” And in July 1969, when Buzz Aldrin blasted off for the moon, he carried a biography of Robert Goddard.

The next day, the New York Times published “A Correction.” Recapping its 1920 mockery, the Times added, “Further investigation and experimentation have confirmed the findings of Isaac Newton in the 17th Century and it is now definitely established that a rocket can function in a vacuum as well as in an atmosphere. The Times regrets the error.”

Every October 19, Robert Goddard remembered “Anniversary Day,” the day he climbed a tree and gazed up.

“There can be no thought of finishing,” he wrote H.G. Wells, “for ‘aiming at the stars,’ both literally and figuratively, is a problem to occupy generations, so that no matter how much progress one makes, there is always the thrill of just beginning.”