AMERICA'S PEACE PLATFORM -- THE LINCOLN MEMORIAL

OMEGA, VA — 1910 — With graduation approaching, eighth graders choose top student Oscar Chapman to buy a portrait for the school.

“Are you sure you want that one?” the clerk asks.

When Chapman brings the portrait back to class, he is expelled. A half-century after the Civil War, a Southern school isn’t ready to honor Abraham Lincoln. But Chapman will have the final word. Decades later, as Undersecretary of the Interior, he was happy to approve a concert by a black woman — at the Lincoln Memorial.

This week, America’s peace platform turns 100. A century ago, on a rainy Tuesday afternoon, President Warren Harding eulogized the president who “maintained union and nationality.” The crowd, including African-Americans segregated by a roped off barrier, applauded and went home, leaving the memorial as steady, as unchangeable as its marble columns. But in a city of monuments, something special about this one would, with time, emerge.

“The Lincoln Memorial is where America gathers to challenge itself,” wrote Jay Sacher in his history of the monument.

This singular, stately memorial embodies the whole tangled web of America’s divides. Proposed in 1867, the idea of honoring a president demonized by half the nation went nowhere. Not until 1901 did momentum gather, but the memorial was soon mired in politics.

“So long as I live,” said House Speaker Joe Cannon, “I’ll never let a memorial to Abraham Lincoln be built in that goddamn swamp.” West Potomac Park was landfill, sand dumped into a swampy riverbank. Was this where Lincoln should be honored?

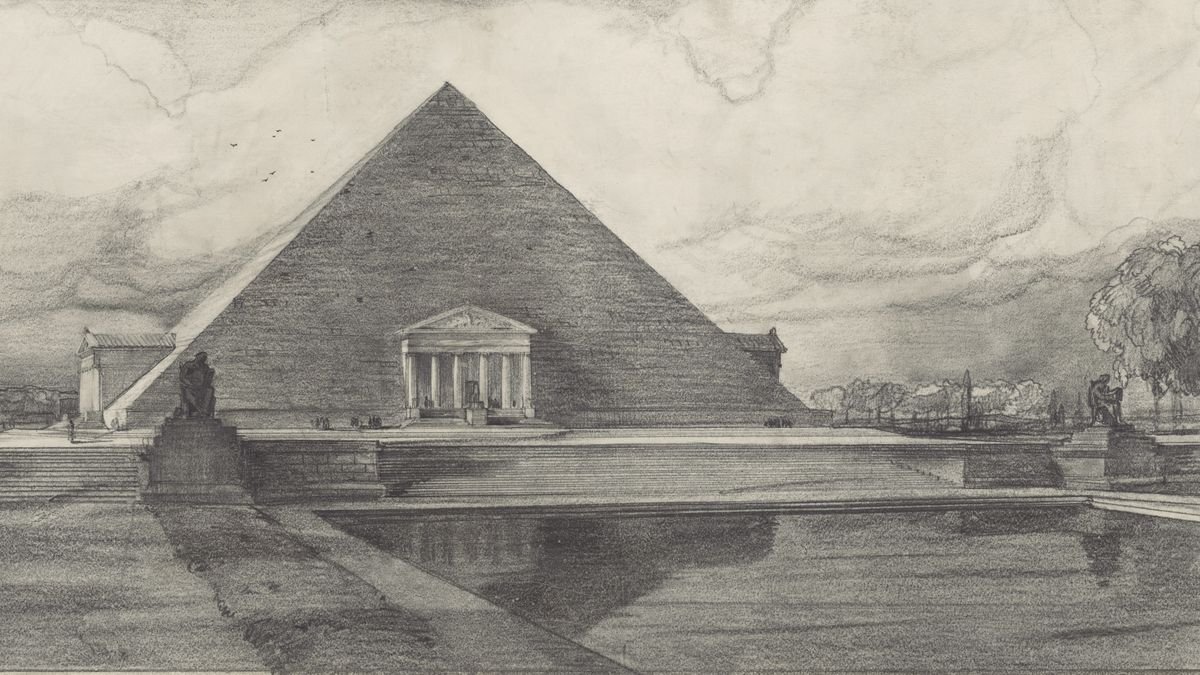

Cannon scuttled bill after bill. Finally after his retirement in 1911, with Washington’s new Mall needing a bookend to offset the Capitol, Congress chose the current site and approved $2 million. A commission considered designs from rotunda to pyramid, and on Lincoln’s birthday in 1914, a former Confederate soldier broke ground.

Like Lincoln, the memorial reached out to the whole country. Marble came from Colorado and Tennessee. Limestone came from Indiana, steel from Pittsburgh. Architect Henry Bacon was from Illinois, sculptor Daniel Chester French from New Hampshire. The author of its dedication was the son of Spanish immigrants. Lincoln’s statue was carved by six sons of an Italian immigrant in the Bronx.

Finally May 30, 1922 — the dedication, the speeches. Yet on into the Depression, the Memorial seemed another tourist attraction. Then a Sicilian-born director and a black singer gave it a “new birth” of meaning.

“The power of the memorial,” Jay Sacher wrote, “resides in its ceaseless reminder to us that history still requires pushing.”

The pushing began in 1939. That spring, denied a concert at segregated Constitution Hall, Marian Anderson sang before 75,000 at the Lincoln Memorial.

That fall, Frank Capra’s “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington” sowed further seeds. Idealistic Senator Jeff Smith is appalled by DC corruption. But with bags packed, ready to resign, Mr. Smith makes a midnight visit to. . .

In 1941, A. Phillip Randolph planned a “Negro March on Washington.” Destination — the Lincoln Memorial. FDR, worried about Southern support, traded an executive order banning segregation in the defense industry for the cancellation of the march. But in 1963, Randolph returned in the march that etched the memorial into the annals of American protest.

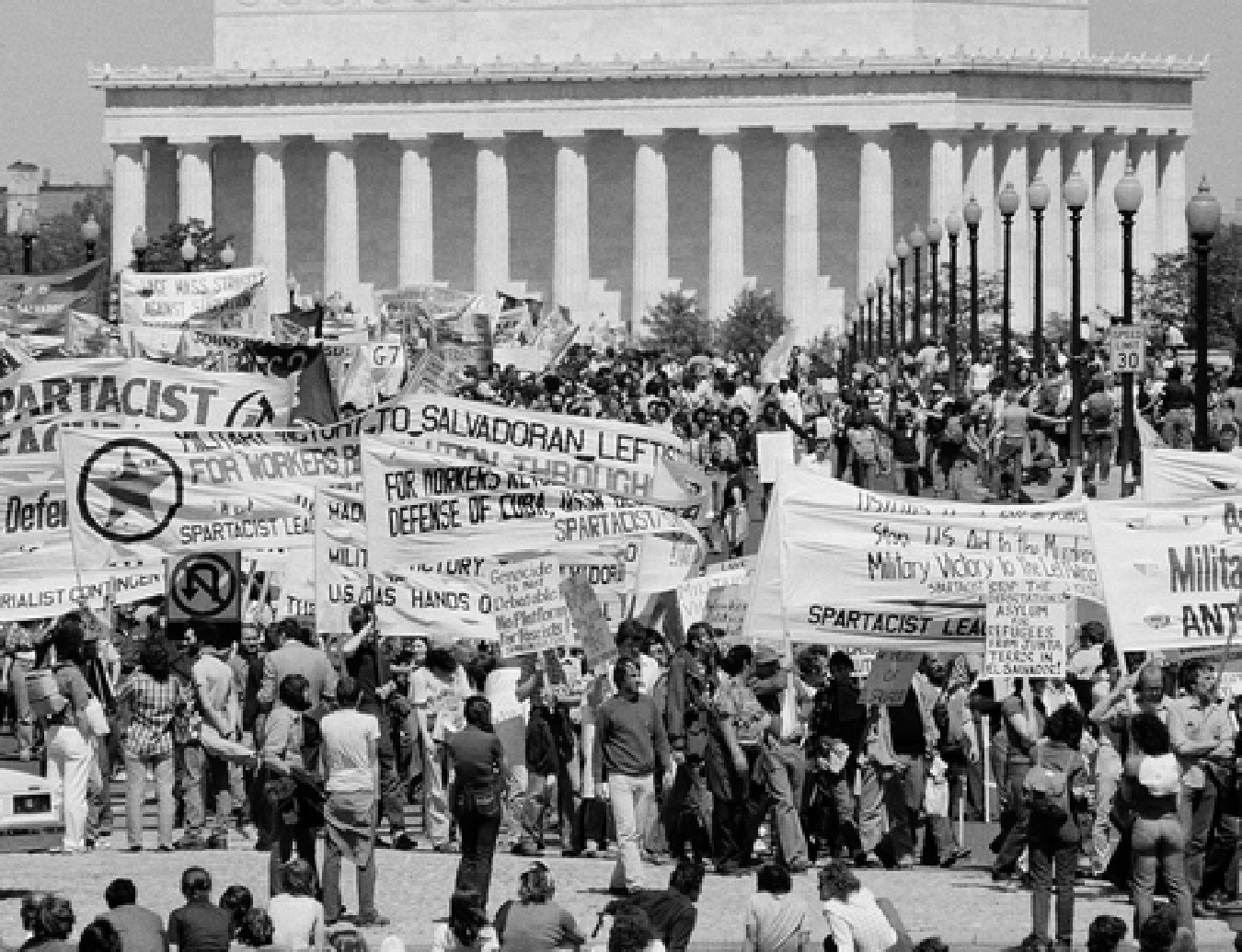

You know the scene. You know the speech. But you may not know the impact on the memorial. When 400,000 reveled in King’s dream, the backdrop made the memorial Ground Zero for Americans seeking justice, equality, peace. On through the Sixties, Vietnam protestors met at the Lincoln Memorial. One night, the president himself dropped by.

Five days after Kent State, protestors an all-night vigil were stunned to see President Nixon come up the steps. Accounts differ. Did Nixon ramble on, or did he, as he remembered, tell them, “I know probably most of you think I’m an SOB but I want you to know that I understand just how you feel.” Either way, the moment showed how vital this singular memorial had become.

A month later, Black Panthers rallied there. That fall, it was Nixon supporters. And on it went. Along with the penny and the $5 bill, the memorial has been featured in five dozen films from “Forrest Gump” to “The Day the Earth Stood Still.” Seven million people visit each year, double the crowds of the most crowded national park.

Easy backdrop? Sentimental symbol? Perhaps, but there may be more. Start with complexity and contradiction. Lincoln often spoke of peace — “There is nothing good in war. Except its ending.” Yet he presided over our bloodiest war. Before becoming president he declared himself “in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.” Yet he freed the slaves and pushed through the amendment that kept them free.

In recent years, complexity and contradiction have marched to the memorial again and again. Bruce Springsteen and Pete Seeger leading an Obama celebration in 2009. A year later, the Tea Party rallying to “restore the honor.” In June 2020, tens of thousands proclaiming Black Lives Matter. That December, 100 white supremacists, then anti-vaxxers. . .

An outrage? OUR Memorial exploited by. . . Relax. If there is one message in this monument, beyond “of the people, by the people, for the people” chiseled on one wall, it is that protest is as American as Lincoln himself.

“The Lincoln Memorial has a long history of allowing Americans to approach from all directions,” Politico wrote. “An understanding of American conflict was woven into the memorial from the start, along with a creative ambiguity that helped to bridge our many divides.”

Peace.