THE MENSCH WHO SAVED A LANGUAGE

LOWER EAST SIDE, 1975 — Feeling a bit meshuga, the bearded long-hairs entered the cafeteria and sat beside the old Jewish men. “Hands were waving,” Aaron Lansky remembered, “fingers pointing, sentences punctuated with heaping spoonfuls of sour cream.” Here was the “old world” surviving into the new. Lansky summoned his nerve.

“Um, Sholem aleykhem.”

Eyebrows went up. “Zogt mir,” one man said. “Ir zent yidishe kinder?” (Are you Jewish children?)

“Vu den,” Lansky replied. (What else?) Lansky then explained his mission. He and his friends had driven from Massachusetts in search of Yiddish books. Surprise rippled through the cafeteria.

“Hey Moyshe,” one man said. “Come over here and see what the kids these days are up to.”

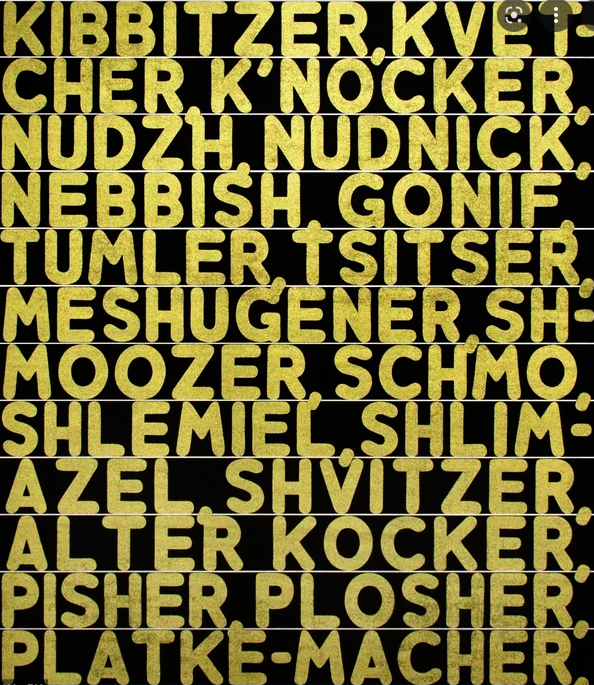

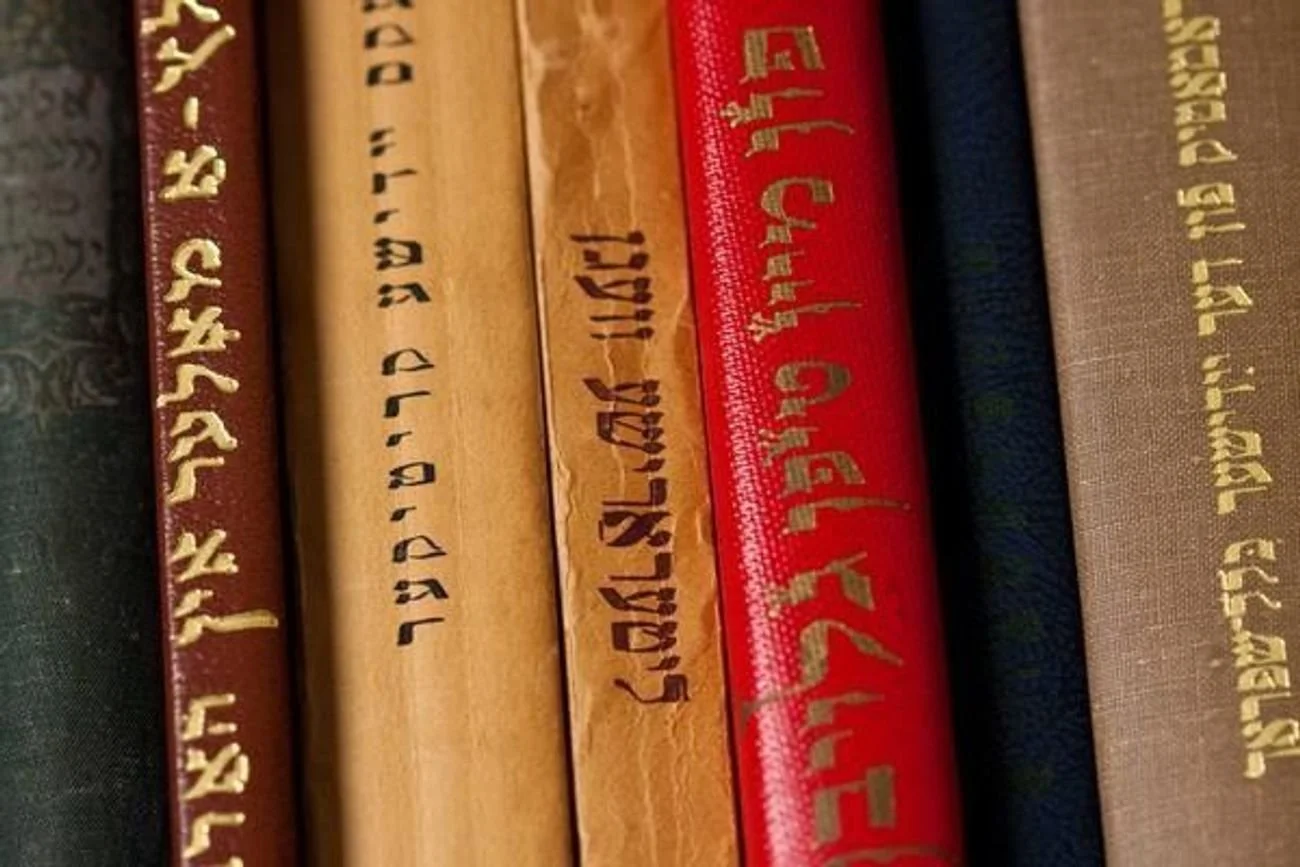

Yiddish is a language of joy, struggle, and sorrow. The joys include the colorful Yiddish words added to English. Bagel, blintz, dreck, glitch, kvetch, schlock, schtick, and a host of terms for what English can only call “a loser.” Nebbish, nudnik, shlemiel, shmendrick, and of course, klutz.

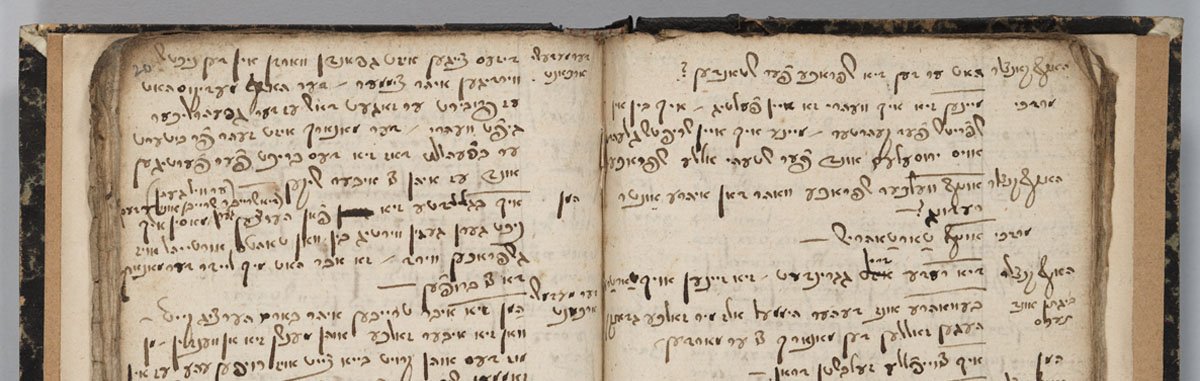

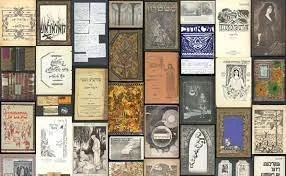

But the struggles and sorrows of Yiddish speak of an “old world” almost extinguished. By 1930, the language culled from German, Hebrew, and other tongues had spawned Yiddish theater and cinema, Yiddish newspapers and novels, and 16 million speakers. Then came the Holocaust.

Eighty-five percent of “the six million” spoke Yiddish. After the war, Jews migrating to Israel began speaking the language once reserved for synagogues — Hebrew. In America, the drive to assimilate led Jews to shun Yiddish, and by 1970, less than a million people worldwide spoke it. Aaron Lansky was not one of them.

In his New Bedford, Massachusetts household, Lansky only heard Yiddish when his grandparents wanted to say something in secret. “We were, after all, American kids, and there was no reason to weigh us down with the past.”

But at Hampshire College, majoring in Jewish Studies, Lansky learned German and Hebrew. To really understand the “people of the book,” however, he needed Yiddish.

“Yiddish is a living chronicle of Jews’ historical experience,” Lansky said, “proof of their peoplehood.”

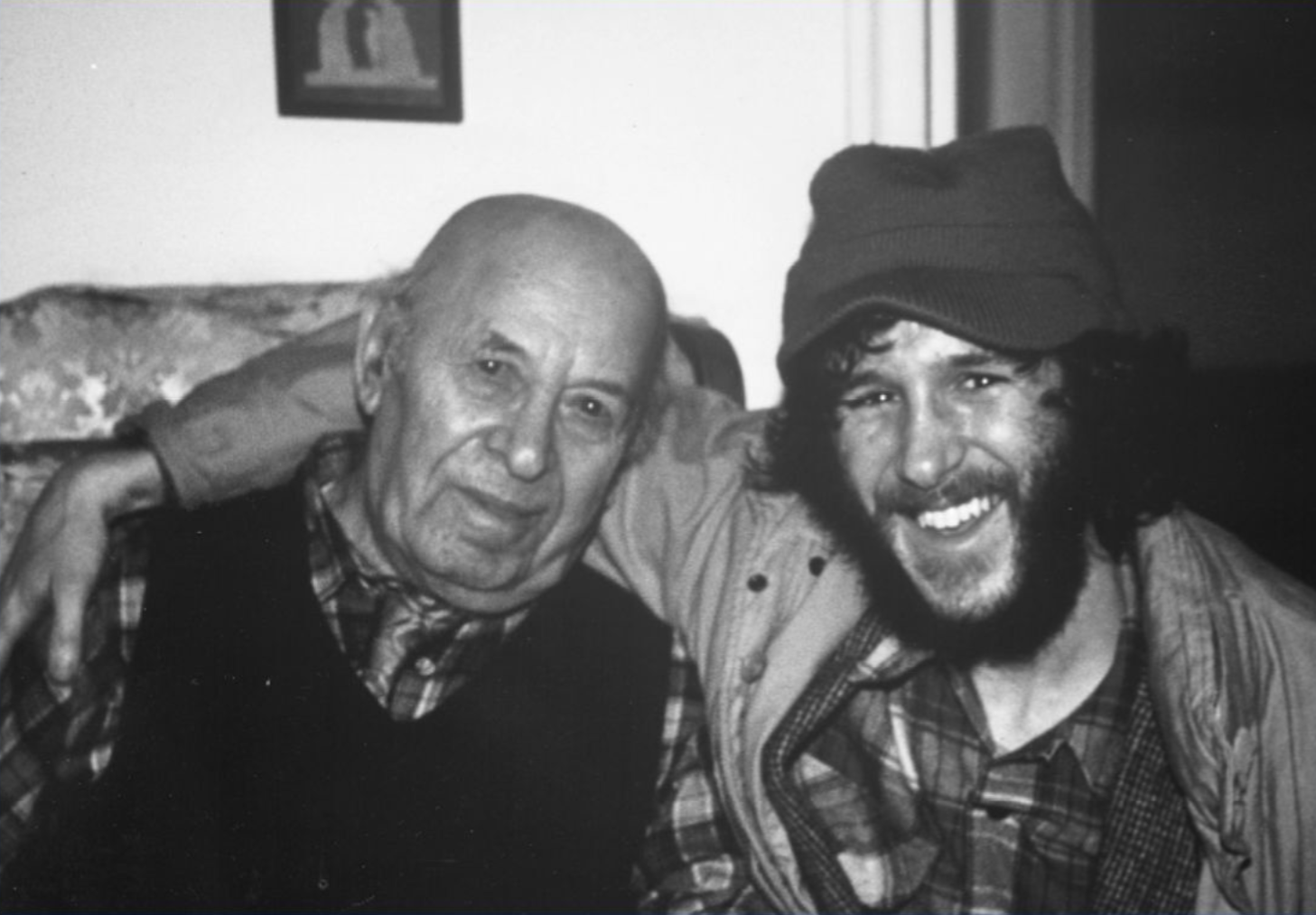

Seeking a tutor, Lansky found Jules Piccus. A professor of Medieval Spanish at UMass, Piccus had grown up in Brooklyn speaking Yiddish and was eager to teach it. When students in that first class lost interest, Lansky convinced Piccus to offer private tutoring over wine and bread. Finishing the only Yiddish textbook, Lansky and other yidishe kinder tackled an Isaac Bashevis Singer novel, then sought more books. But where?

Lansky searched used bookstores. He wrote to struggling Yiddish publishers in New York. He found only a few titles. “Don’t think the books are going to come to you,” Piccus told him. “If you want Yiddish books you’ve got to go to them. And while you’re there you can stop at Guss’s Pickles on Hester Street and bring me back a gallon of half-sours.”

In that cafeteria on the Lower East Side, Lansky and his long-haired friends were “examined, cross-examined, hugged, kissed, smeared with lipstick, pinched, and blessed.” They were then sent to certain bookstores. The first had no Yiddish titles, but in another, piled on the second floor, strewn with shmutz and dreck, were hundreds of tattered Yiddish books.

The neglected books suggested a darker picture. The Holocaust had been the first blow, Hebrew the second. Now death was about to finish off Yiddish. Old Jews were dying off and their children were scrapping entire Yiddish libraries. Who would save these books, this literature, this culture?

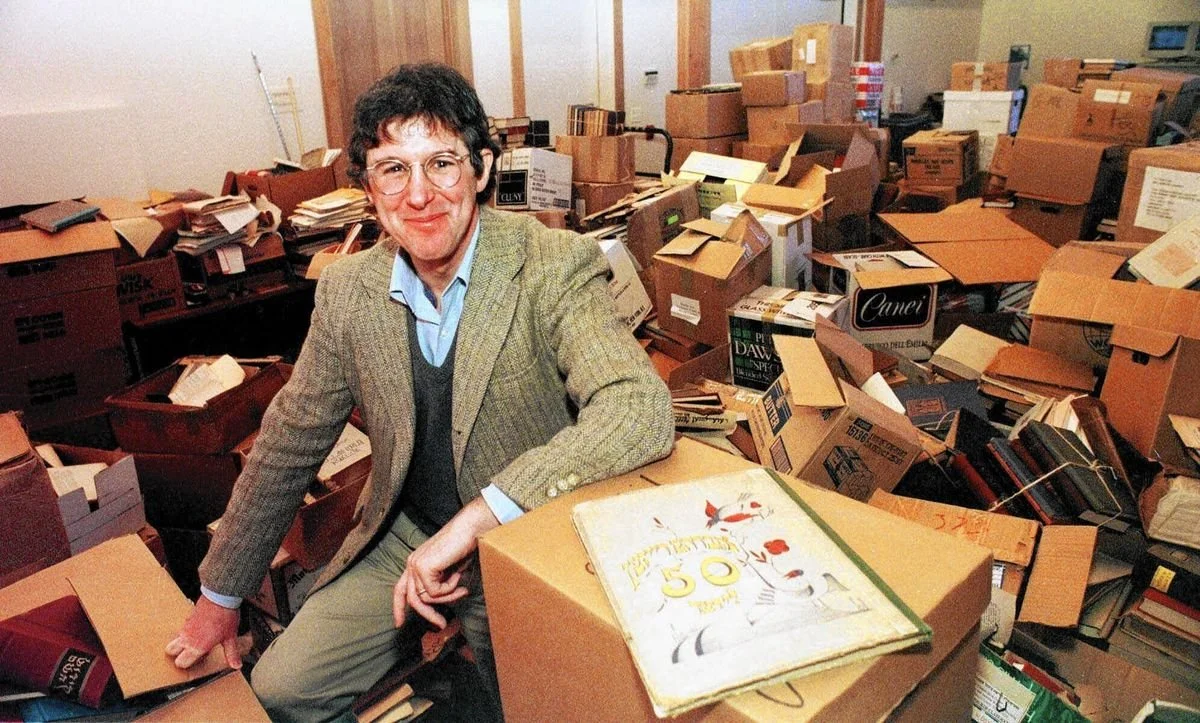

In 1978, Lansky took a leave from grad school. Renting an old truck, enlisting friends, he began gathering books. From attics and dumpsters. From bookstores and basements. His crew visited aging Jews who “sat us down at their kitchen tables, plied us with tea and cakes, and handed us their personal libraries, one volume at a time. . . . People cried and poured out their hearts.”

Skeptics abounded. Why save Yiddish books? No one read them. A common kvetch was, “Better you should study the Torah.”

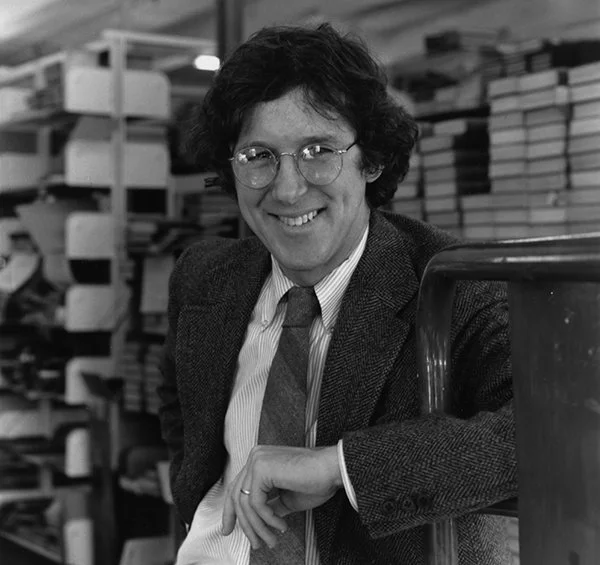

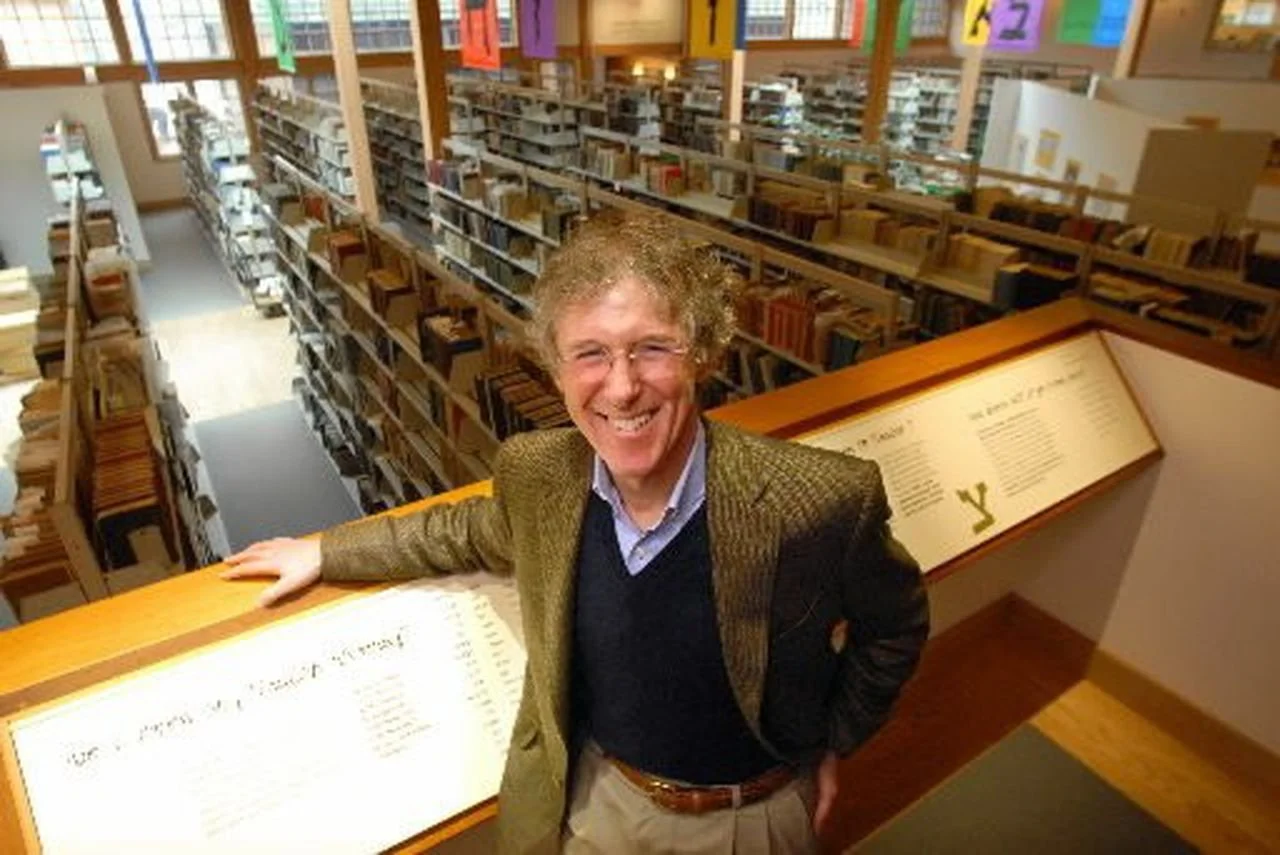

Scholars estimated that just 75,000 Yiddish books remained, but Lansky and his friends kept gathering, collecting, shlepping box after box. By 1980, they had a million books. Renting an abandoned school in Amherst, Massachusetts, Lansky opened the National Yiddish Book Center. The center soon started Yiddish lessons and a Yiddish summer camp for kids. Books began to pour in from around the world. A MacArthur Genius grant allowed Lansky to expand further.

In 1997, the Yiddish Book Center opened at Hampshire College, where it continues to thrive. That year, Stephen Spielberg lent his name to a database of Yiddish books online. The center started an annual music festival — Yidstock. Along with cultural exhibits onsite, the center features lessons, Great Books programs, translation workshops, and more.

Saved from the dustbin of history, Yiddish is now in revival. Google Translate and the language app Duolingo offer Yiddish. Two dozen colleges give classes. And Yiddish is a recognized language in Moldovia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

Yiddish, of course, has words for all this. Mensch — an all around good guy — describes the affable Lansky. Chutzpah hints at the nerve it took to revive a dying language. And Mazel tov offers congratulations. But Lansky opens his memoir with an even bolder claim about Yiddish.

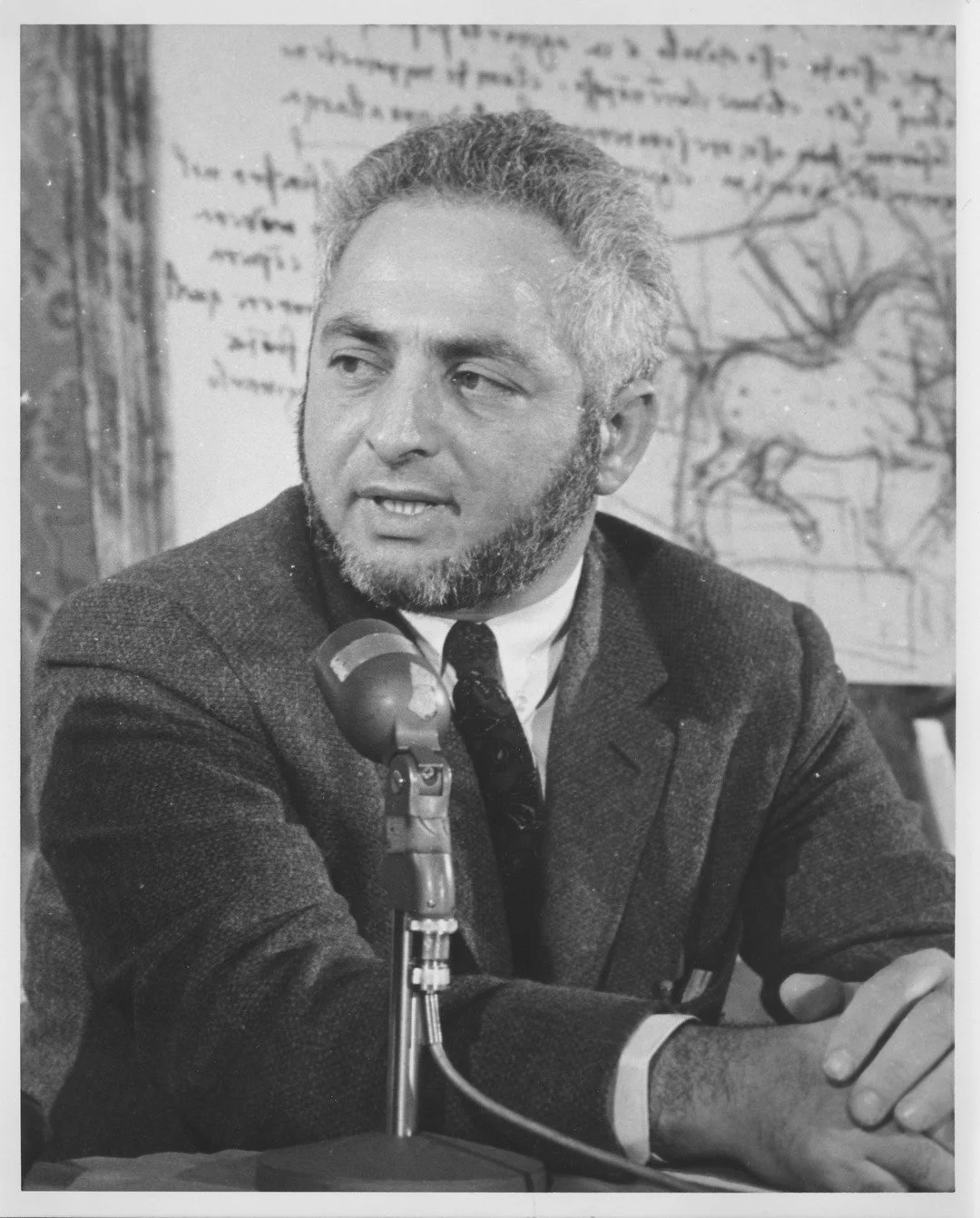

Seems the world’s most esteemed Yiddish scholar, forced to flee the Nazis, was giving talks on Yiddish in Manhattan. Almost no one came, but Max Weinreich kept teaching the joys and sorrows. Why? Why go on?

“Because Yiddish has magic,” Weinreich said. “It will outwit history.”