GRANDMA MOSES AND THE ART OF AGING

HOOSICK FALLS, NY — 1938 — The drug store had the usual local products. Jams. Jellies. Maple syrup. But on one wall hung three paintings of a bygone era — of homespun Thanksgivings, winter play, and farm life without tractors or troubles.

At five bucks apiece, collector Louis Caldor bought all three, then asked the clerk who had done them. He was soon standing in the kitchen of a nearby farm gazing at ten more paintings. “I’m going to make you famous,” Caldor told the artist. The bespectacled old woman scoffed. Who would want the “hobby paintings” of a 78-year-old grandma?

Grandma Moses has a unique place in American art. Folk artists abound, and everyone knows some retiree who lives to paint. But throughout the 1940s and into the atomic age, Grandma Moses captured the yearnings of a hurried world.

“The world she shows us is beautiful and it is good,” said one fan. “You feel at home in all these pictures, and you know their meaning. The unrest and the neurotic insecurity of the present day make us inclined to enjoy the simple and affirmative outlook of Grandma Moses."

Anna Mary Robertson was born two months before Lincoln’s election. Her death was eulogized by JFK. In her 101 years, she toiled as domestic helper, farm wife, and mother of ten, though five children died in infancy. From homes in Virginia and upstate New York, she saw the world march from horse and buggy to Model T’s, jet planes, and space travel. But she never forgot the life left behind.

Though she decorated the home she shared with Thomas Moses, she was too busy for art until her husband died and she left the farm to her son. She soon took up embroidery, but arthritis ended that delicate work. Her sister suggested painting.

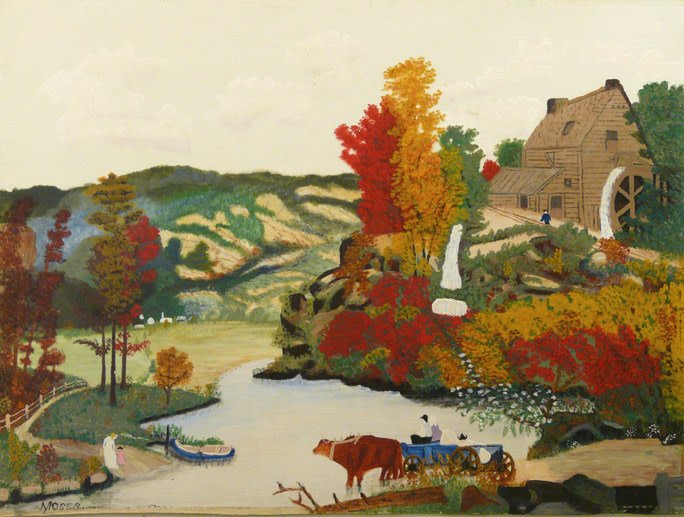

Her first works used leftover house paint applied to fiber board. Recalling something “old-timey,” she would grab a brush. “Then I'll forget everything, everything except how things used to be and how to paint it so people will know how we used to live."

When the nice man who dropped by her kitchen took all her paintings to New York, she had no expectations. But Louis Caldor brought Moses’ works to galleries and museums. Many were impressed — until they heard the artist’s age. Why invest time in someone so old?

Then in September 1939, the Museum of Modern Art put three Moses’ paintings in a show of “Contemporary Unknown American Painters.” A Manhattan gallery owner soon saw in Moses what Picasso had seen in other folk artists. Purity. Innocence. Natural talent.

From her first gallery show, “What a Farmwife Painted,” Moses career took off. The New York Herald nicknamed her “Grandma Moses” and when, in black dress and bonnet, she spoke at Gimbel’s Department Store, she became an instant folk hero.

Her work was soon displayed across America. Critics called it "fresh," "charming," "full of naive and childlike joy.” Her winter scenes, cluttered with frolicking people, were compared to Breughel. Her lack of formal training suggested Henri Rousseau. Moses had never heard of either. She kept painting.

She worked daily in a small studio next to her farmhouse kitchen. Seated in a battered swivel chair, perched atop two pillows, she painted onto masonite laid flat on a table. From the top down. “First the sky, then the mountains, then the hills, then the trees, then the houses, then the cattle and then the people."

She studiously avoided the modern. No tractors, cars, not even telephone poles. She focused on pure rural America: “Catching the Thanksgiving Turkey,” “Haying Time,” “The Old Covered Bridge. . .” Asked if she might paint a contemporary scene, she bristled.

“I’ll not paint something we know nothing about, might just as well paint something that will happen a thousand years hence.” Critics had a name: “genuine American primitive.” And genuine Americans, crammed into suburbs, stuck in traffic, menaced by The Bomb, loved it.

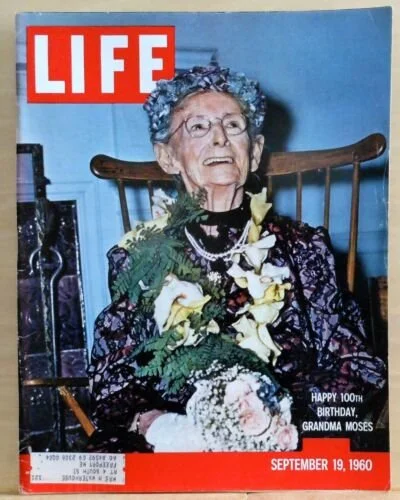

Approaching her 90s, Grandma Moses was as much a commodity as an artist. Her works graced calendars, cards, tiles, and fabrics. President Truman served her tea at the White House. TIME, LIFE, and Edward R. Murrow interviewed her. Unflustered by fame, she continued to paint daily, finishing 1,500 works in two decades. “Painting’s not important,” she said. “The important thing is to keep busy.”

In 1960, on her 100th birthday, New York celebrated “Grandma Moses Day.” But the following August, a fall sent her to a nursing home. She died in December. Doctors said she “just wore out.” JFK said, “The death of Grandma Moses removed a beloved figure from American life. The directness and vividness of her paintings restored a primitive freshness to our perception of the American scene. . . . All Americans mourn her loss.”

While some dismiss her as a nostalgic fad, Moses’ works can be seen in many museums, including the Smithsonian, Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum, and the Metropolitan in New York. In 2006, a Grandma Moses painting sold for $1.2 million. But beyond art, her “simple and affirmative outlook” endures, suggesting that “it’s never too late.”

“I look back on my life like a good day's work,” she wrote. “It was done and I feel satisfied with it. I was happy and contented, I knew nothing better and made the best out of what life offered. And life is what we make it, always has been, always will be.”