WHEN 'WE SHALL OVERCOME' WENT VIRAL

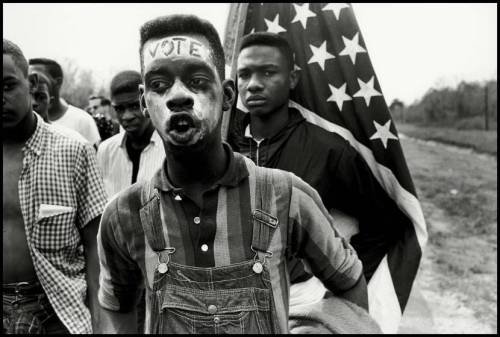

WASHINGTON, D.C., MARCH 1965 -- The Civil Rights movement teeters on a hinge called Selma. Blacks are marching, singing, rallying for the right to vote. Cops respond with nightsticks and cattle prods. Then in February, young Jimmie Lee Jackson is shot.

Jimmie Lee Jackson, Martin Luther King says at the funeral was murdered by a sheriff's bullet. But he was also "murdered by the timidity of a federal government that is willing to spend millions of dollars a day to defend freedom in Vietnam, but cannot protect the rights of its citizens at home."

The previous summer, capping his Civil Rights Bill, President Lyndon Johnson asked his attorney general to write "the goddamn best, toughest voting rights act that you can devise." But come November, despite winning by a landslide, voting rights would have to wait.

"Something is going to come up," Johnson told aides. "Something like the Vietnam War." So "get off your asses. . . before the aura and the halo that surround me disappear."

His first priority is Medicare. A voting rights bill will be trickier. “We can’t risk defeat or dilution by filibuster on this one. This bill has to go up there clean, simple and powerful. Second, we don’t want this bill declared unconstitutional. This can’t be just a two-line bill. The wherefores and the therefores are insurance against that.”

On into March, while Selma boils, LBJ hesitates. In the White House, Lady Bird Johnson sees "a fog of depression." Then comes "Bloody Sunday.,” blacks marching across the Edmund Pettis Bridge — trampled, routed, one man killed.

Five days later, LBJ meets King in the White House. Emerging from the meeting, King tells the press that a voting rights act will be proposed "very soon." And on Sunday, the president announces he will speak to Congress the next night. But what will he say?

On Monday morning, Richard Goodwin, first hired by JFK, begins re-writing an old draft. By noon, he is sending pages to the president. LBJ corrects, adds, edits. "You remember, Dick, that one of my first jobs after college was teaching young Mexican-Americans down in Cotulla,” Johnson tells Goodwin. “I thought you might want to put in a reference to that.”

By 7:00 p.m., the speech is done, but too late to make the teleprompter. LBJ will have to read from a notebook. At 9:00 p.m. he walks into the House. "I started out slow," he will recall.

I speak tonight for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy. . .

Sensing the tension, he accelerates.

At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man's unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama..."

Then, drilling the camera and the audience, he says, There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem.'

Soon Johnson turns to that first teaching job.

My students were poor and they often came to class without breakfast and hungry. And they knew even in their youth the pain of prejudice. They never seemed to know why people disliked them, but they knew it was so because I saw it in their eyes. . . And somehow you never forget what poverty and hatred can do when you see its scars on the hopeful face of a young child.

But the social programs would have to wait, because the speech on March 15, 1965 is remembered for a single phrase. Chanted throughout the Civil Rights Movement, the phrase had most recently been heard in Selma. Now, introducing the Voting Rights Act, the president of the United States. . .

What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it's not just Negroes, but really it's all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.

Watching on TV in Alabama, King's aides are stunned. "Did he just say that?" King fights tears. In Congress, Southerners slump. One says, "Goddamn!" But the rest rise for a standing ovation.

After the speech, sipping Scotch, LBJ takes calls from friends, and from Martin Luther King. "It is ironic, Mr. President," King says, "that after a century, a Southern white president would help lead the way toward the salvation of the Negro."

"Thank you, Reverend," LBJ replies. "You're the leader who is making it all possible."

Later Johnson turns to his speechwriter. "You know Dick, I understand why he's surprised, why a lot of folks are surprised, but I'm going to do it. Hell, we're just halfway up the mountain. Not even half."