DEMOCRACY FOR A DIME

A century ago, talk was cheap. A movie cost 15 cents, a phonograph record 75¢. Magazines went for a nickel, newspapers a penny. Books, however, were no bargain.

A new hardback of The Great Gatsby sold for two bucks, half a worker’s daily wage. Wait for the paperback? Forget it, there were no paperbacks. Used book stores did not exist, and libraries were for urbanites. How could the common American, home from a hard day’s work, afford a book? The answer came from that hotbed of American publishing — Kansas.

Forget Simon, say farewell to Schuster. The “Henry Ford of literature,” the man who put books — a half BILLION books — into the hands of everyday Americans had a name readers barely knew.

Growing up in Philadelphia, son of Jewish immigrants who fled Russia’s pogroms, Emanuel Julius read any book his father, a bookbinder, handed him. But it took a cheap chapbook, Oscar Wilde’s “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” to inspire him to democratize American reading.

“It was winter, and I was cold,” Julius recalled. “But I sat down on a bench and read that booklet straight through, without a halt, and never did I so much as notice that my hands were blue, that my wet nose was numb. . . I'd been lifted out of this world - and by a ten-cent booklet. I thought how wonderful it would be if thousands of such booklets could be made available.”

Julius made a modest living in journalism editing the Socialist weekly Appeal to Reason. But after World War I, with American Socialism under attack, readership plummeted. Julius, by then having added his wife’s surname and a hyphen, appealed to Appeal’s 175,000 readers. Send $5 and get the first fifty titles fresh off his press in Girard, Kansas.

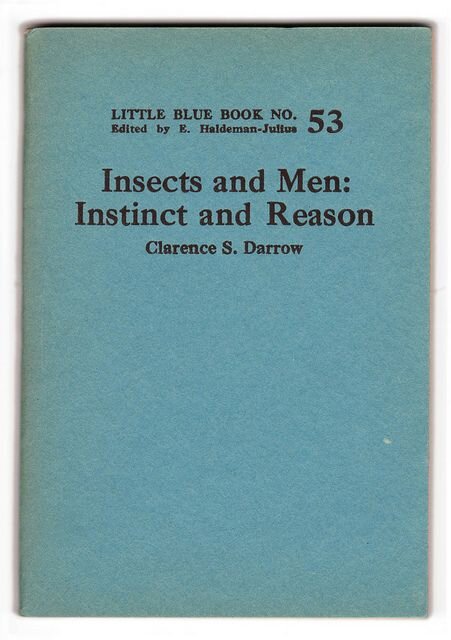

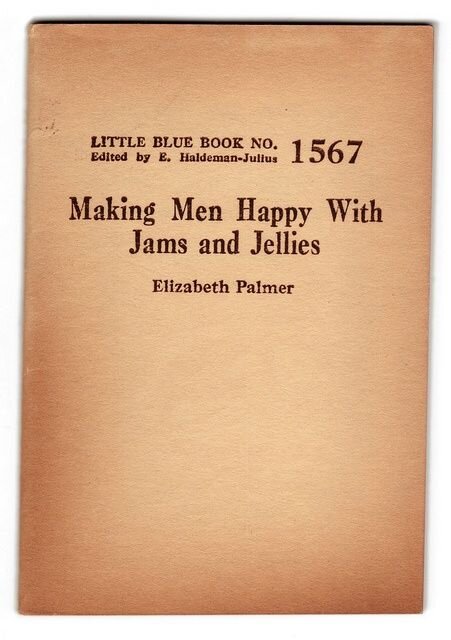

Five bucks for fifty books? Ten thousand readers couldn’t resist. With titles ranging from Shakespeare to “How to” tracts, from Goethe to H.G. Wells, The Little Blue Books were born.

Throughout the 1920s and into the Depression, the Little Blue Books saturated America. A master marketer, Haldeman-Julius sold his books not just in bookstores but in drug stores, toy stores, even vending machines. Most, however, sold by mail.

One ad boasted: “At last! Books are cheaper than hamburgers!” Not just cheap, Little Blue Books were portable, easy to slip into a pocket. Readers were forever grateful.

“Riding a freight train out of El Paso,” Western novelist Louis L’Amour remembered, “I had my first contact with the Little Blue Books. Another hobo was reading one, and when he finished he gave it to me. The Little Blue Books were a godsend to wandering men and no doubt to many others. . . I carried ten or fifteen of them in my pockets, reading when I could.”

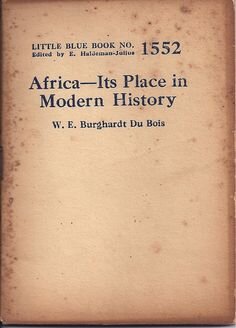

New titles, new series appeared monthly. “The People's Pocket Series,” “Encyclopedia of Humor,” “Knowledge of Life,” “University in Print.” Eager to join the ranks of Thoreau, Kant, and Balzac, noted authors like Will Durant and W.E.B. DuBois wrote short tracts for wide distribution. With an average order of 35 books, the little press in Kansas churned on.

But Simon and Schuster were no fools. In the mid-1930s, the first paperbacks, with tight binding and glossy covers, came from England. By World War II, soldiers were carrying the latest Hemingway or Steinbeck in their packs. Then after the war, the Little Blue Books faced literature’s timeless foe — politics.

Haldeman-Julius, a lifelong Socialist, included many leftist tracts in his titles. Politics sold poorly compared to “Home Interiors: Practical Hints on Interior Decoration,” but in 1948, with Cold War tensions rising, Haldeman published “The FBI — The Basis of an American Police State.”

J. Edgar Hoover? Not a big reader, let’s say. And when the FBI investigated the Little Blue Books, Hoover saw Little Red Books. “The Soviet Constitution,” “The Soul of Man under Socialism,” even "Homo-Sexual Life."

In 1951, Haldeman-Julius was convicted of tax evasion. A month later he drowned in his swimming pool. The Little Blue Books kept coming, but few bought them. Books were cheaper, and TV was making talk so cheap it seemed shabby. The little press in Kansas struggled on until 1978 when it burned to the ground.

Today, Little Blue Books are a fond memory and a collector’s item. Books sell for a few bucks each on Etsy or ebay. Complete collections, nearly 2,000 titles, are catalogued in university libraries.

Emanuel Haldeman-Julius had no illusions about his work. “At the close of the 20th Century,” he wrote, “some flea-bitten, sun-bleached, fly-specked, rat-gnawed, dandruff-sprinkled professor of literature is going to write a five-volume history of the books of our century. In it a chapter will be devoted to publishers and editors of books, and in that chapter perhaps a footnote will be given to me.”

But the Little Blue Books were more than a footnote. For a half century, they offered democracy for a dime. J. Edgar Hoover did not get it but one Founding Father did.