WALKING AMERICA: THE LONGEST JOURNEYS

Afoot and light-hearted I take to the open road,

Healthy, free, the world before me,

The long brown path before me leading wherever I choose.

— Walt Whitman, “Song of the Open Road”

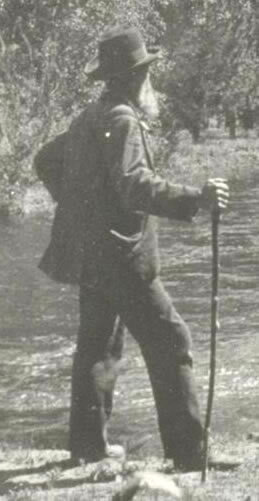

CINCINNATI, SEPT 1884 — Stepping onto a gravel road, he makes a final check. Knapsack. Tobacco. Fish hooks. Revolver. Pen and paper. Hunting knife in his belt. Three hundred dollars in gold coins sown into his suit.

9:00 a.m. Time to get going. With no fanfare, no goodbyes, Charles Lummis starts walking. His destination — a distant boomtown of 12,000. Locals call it Los Angeles.

Walking is a universal pastime, but America’s vast distances have spawned a romance with the open road. Despite Amtrak and interstates, walking from sea to shining sea is more popular than ever. Of Wikipedia’s 45 coast-to-coast walkers, two-thirds have made the trek since 2010.

Reasons vary. When trudging through rain and snow, past barking or lunging dogs, suffering blisters and callouses, marching 15-20 miles a day, a cause sure helps. But it’s not about the fund-raising.

“I was after neither time nor money, but life,” Charles Lummis wrote in A Tramp Across the Continent, “life in the truer, broader, sweeter sense, the exhilirant joy of living outside the sorry fences of society.“ And then there is the call of the country. “I am an American,” Lummis wrote, “and felt ashamed to know so little of my country.”

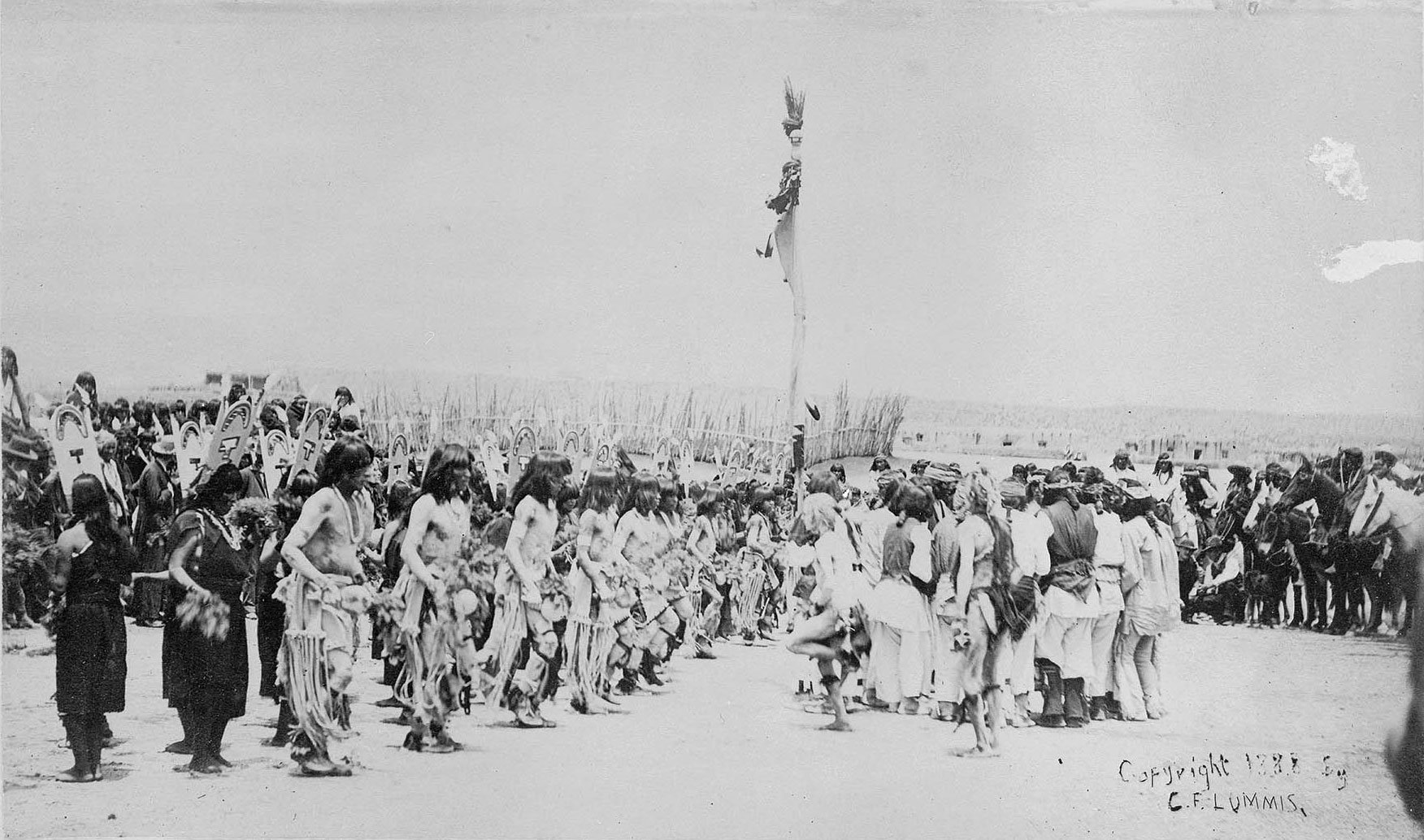

Lummis found the Plains endless and boring, but the Rockies and Southwest provided “exhilirant joy.” Chased by a cougar, fending off rattlesnakes, Lummis befriended cowboys and lived with the Hopi and Navajo. He broke his arm, nearly died crossing the Mojave, and made it to “God’s country” in 143 days. The Great American Trek had taken its first long step.

In Wanderlust: A History of Walking. Rebecca Solnit writes: “Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world are aligned, as though there were three characters finally in conversation together, three notes suddenly making a chord.”

John Muir walked “a thousand miles to the Gulf.” Thoreau walked because “all good things are wild and free.” New Yorker Matt Green walked every single street in the five boroughs. Paula Francis made a 10,000 mile Happiness Walk. The open road is one reason. Peace might be another.

On New Year’s Day 1953, 44-year-old Mildred Norman took the name “Peace Pilgrim” and hit the road. Vowing to “remain a wanderer until mankind has learned the way of peace,” Peace Pilgrim walked for the rest of her life. She refused to carry money. Depending on the kindness of strangers, she crossed the U.S. on foot six times and at age 72, was starting another trek when she died in a car accident.

On New Year’s Day 1999, Doris Haddock set out from Pasadena’s Rose Bowl with campaign finance as her cause. Thirteen months later, “Granny D,” age 90, made it home to New Hampshire, traversing final miles on cross-country skis.

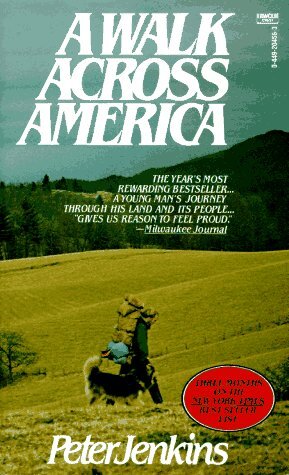

Peter Jenkins sought a separate peace. In October 1973, disillusioned by Vietnam, Watergate, and his own divorce, Jenkins walked out of Alfred, NY. With his Alaskan malamute, Cooper, walking along, Jenkins headed for New Orleans. He’d been warned about the “redneck South,” but mile after mile, Jenkins found an America that never made the nightly news.

Jenkins was welcomed into homes, often for months. He lived with a hermit in Appalachia, a black family in Tennessee, on a commune. In churches and homes, Jenkins met a few mean folks but found in the rest a generosity that, “it began to seem to me, gushed out of the spirit of this land.”

Jenkins’ walk across America lasted six years. En route, he wrote for National Geographic, wrote a best-selling book, and finally reached the Oregon Coast, walking with the woman he met and married in New Orleans.

“I had started out with a feeling of burning dullness and desperation,” Jenkins wrote. “Now I was filled with a thrill and expectation of new discovery.”

And there were others. In 2016, Bill Bucklew made it in 67 days — the fastest. The following year, Noah Barnes, age 11, raising money for diabetes, became the youngest. In 1986, The Great Peace March was the largest.

Setting out from L.A. City Hall to the cheers of thousands, 1,200 trekked east with plans for drawing crowds to the cause of nuclear disarmament. The march’s sponsor soon went broke, sending half home, but on across America, speaking in churches and classrooms, some 400 people carried their cause all the way to Washington, D.C.

Afoot and light-hearted, America walks on. Who knows, in the wake of a pandemic, how many epic walks are being planned. But when all the miles are crossed, all the aches soothed, it will not have been about the cause, not even about the feet.

“The mind is also a landscape of sorts,” Rebecca Solnit wrote, “and walking is one way to traverse it.”

And then there are the people, as Walt Whitman knew.

Now I see the secret of the making of the best persons,

It is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth.