THE TOWN THAT SECEDED TO SUCCEED

MINNESOTA’S IRON RANGE — 1977 — It takes a special kind of person to settle in Minnesota’s Mesabi Range. Where wind chills plunge to minus double digits. Where stories are told of frozen fingers, frozen pipes, a land as unforgiving as its iron. Miners come and go but in tiny hamlets, locals hunker down. In tough times, a sense of humor helps.

Founded in 1910, Kinney, Minnesota was not built to last. Just a 3 x 4 block grid an hour north of Duluth, Kinney was a boomtown that boomed to 1,200 in the 1920s, then went bust. By 1970, Kinney had just a few dozen houses, a library, a town hall, and Mary’s Bar.

That’s Mary behind the bar. Born and raised on the Iron Range, Mary Anderson, locals knew, was “smart. . . friendly. . . a feisty little old lady.” Still, locals were surprised when Mary, a nurse by day and bartender by night, ran for mayor in 1973. At 58, she became the Iron Range’s first female mayor. Then the trouble started.

The following summer, fire broke out in a downtown home. When Kinney’s fire truck arrived, one hydrant after another barely trickled water. Mary watched as her parents’ house burned to the ground.

Kinney’s water was not just scarce; it was scary. Laced with iron and manganese, it left dark rings on glasses and amber stains on clothes. Old pipes were rotting, rusting, but a new water system would cost $186,000.

For three years, Anderson and her city council played politics. They wrote to state agencies. They filed applications — in triplicate — with the FHA and HUD. Anderson visited state offices, sitting for hours just to be heard. “Those people at the agencies really hate me,” she said. And the town of Kinney got. . . Nothing.

“We were competing with every town in Minnesota, small and large,” remembered town attorney James Randall.

Then one night, a bunch of councilmen were whooping it up down at Mary’s Bar when the Mayor got mad. “We can’t get any money,” Mary said. “We should get the heck out of this country. “ At the bar, Attorney Randall replied, “Well, I suppose we could secede and apply for foreign aid as a foreign country.”

As talk went on, the idea ”kept havin’ legs,” Randall recalled. “And Mary said, ‘Jim, why don’t you draft somethin?’ And I did.”

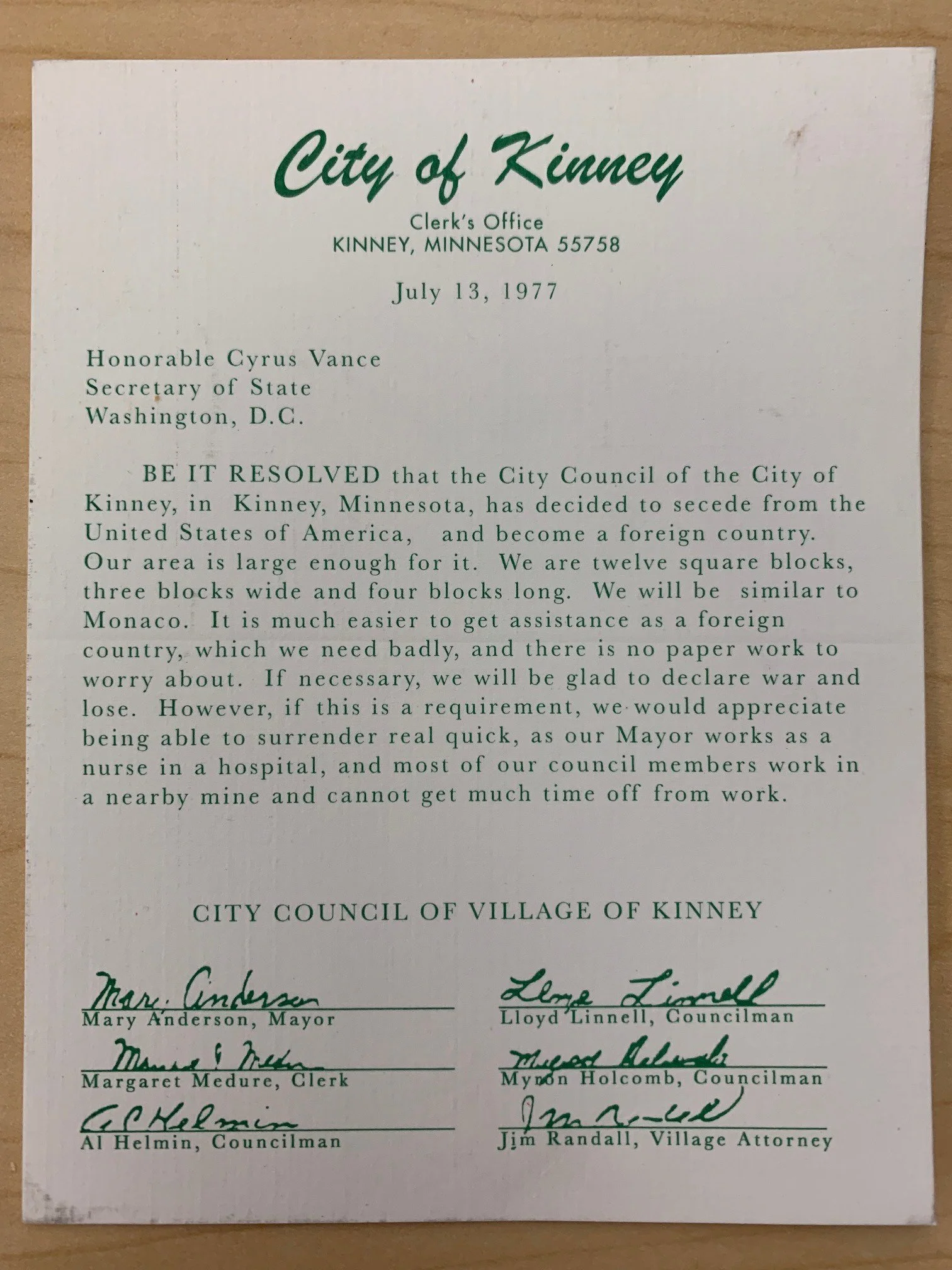

BE IT RESOLVED that the City Council of the City of Kinney, in Kinney, Minnesota, has decided to secede from the United States of America, and become a foreign country. Our area is large enough for it. We are twelve square blocks, three blocks wide and four blocks long. We will be similar to Monaco. . .

The resolution was firm but fun.

. . . If necessary, we will be glad to declare war and lose. However, if this is a requirement, we would appreciate being able to surrender real quick, as our Mayor works as a nurse in a hospital, and most of our council members work in a nearby mine and cannot get much time off from work.

On July 13, 1977, Randall sent the resolution to Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. Again, nothing. But come January, the new reporter for the Mesabi Daily News was having a beer down at Mary’s.

“You what?”

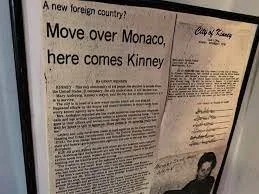

On February 5, the newspaper’s front page read “Move over Monaco, Here Comes Kinney!” Two days later on NBC Nightly News, David Brinkley told the nation of how Kinney’s “town fathers (sic) voted to secede from the union.” And suddenly. . .

— “Kinney Dons Trappings of Nationhood in War for Water” (Duluth News Tribune);

— “Range Town Would Go to ‘War’ for Aid” (Minneapolis Star);

— “Town Waves Secession Flag” (Christian Science Monitor);

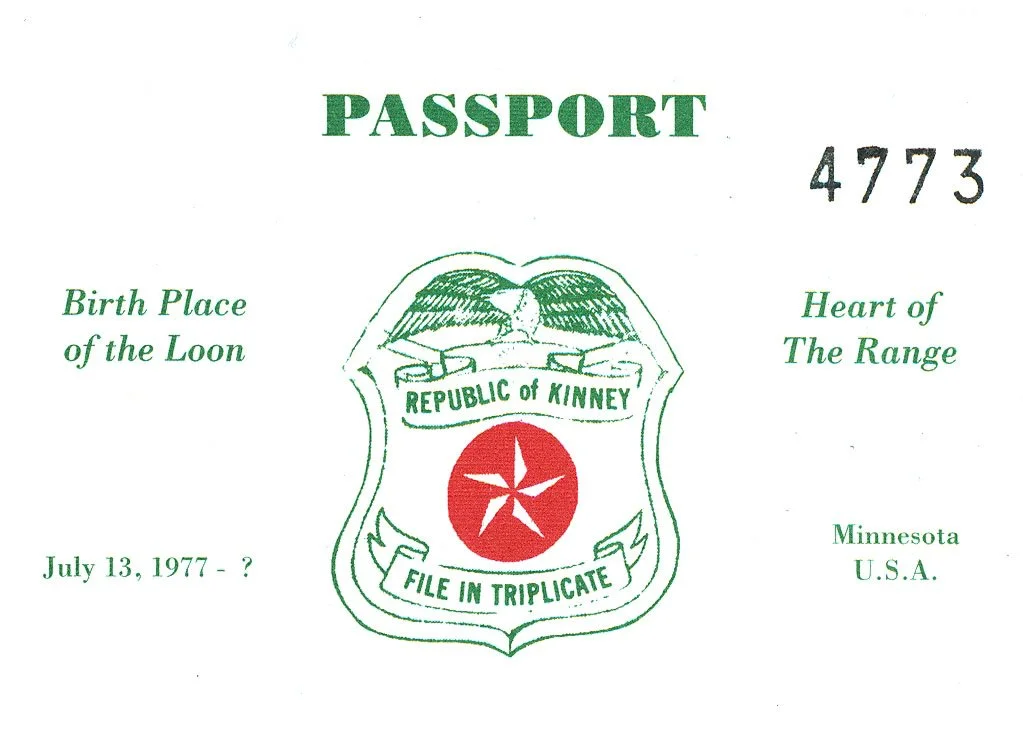

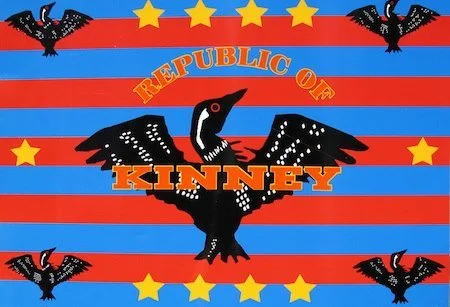

Phones at city hall and at Mary’s Bar began ringing. By summer, tourists were dropping by, some from overseas. Someone suggested passports, so Randall designed a shield with Kinney’s national motto — “FILE IN TRIPLICATE.” Local schools held a flag design contest. Some residents changed their addresses to Republic of Kinney 55758. When a local gave the town a canoe, it became the republic’s navy.

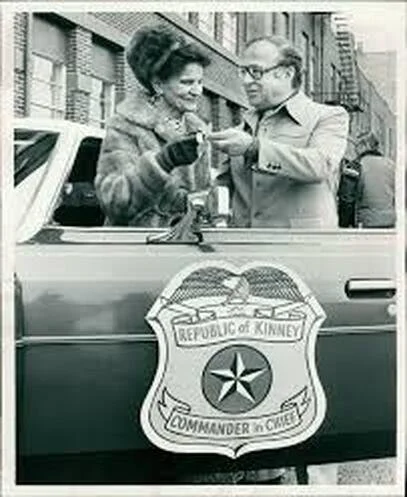

The spirit caught fire on the prairie. When Kinney’s only police car broke down, a pizza mogul in Duluth sent 10 cases of frozen pizza and a beat up Ford LTD. The town put its shield on its new cruiser. Then Minnesota governor Rudy Perpich, receiving his official Kinney passport, wrote back “recognizing Kinney as a sovereign nation.” Two thousand more passports sold at a buck each, bankrolling new furniture and a refrigerator for the town hall.

And the water?

No foreign aid came, but in March 1978, Minnesota’s Iron Range Resources and Rehabilitation Board coughed up $198,000. By 1981, with new pipes and hydrants, Kinney had the water it deserved. And the town did not have to go to war.

“We did it,” Randall remembered. “We pulled it off. We declared victory and won. Long live the republic of Kinney!”

For several years, an annual Republic of Kinney Day filled the local park and sold more passports. In 2002, 87-year-old Mary Anderson stepped down as mayor, and bartender. Five years later, on the 30th anniversary of independence, she was the grand marshal in a three-day celebration with parades, fireworks, and a customs booth.

Months later, when Anderson died, 100 people, more than half the town showed up at her funeral. It takes a special kind of person. . . Long live the Republic of Kinney!