STUDS TERKEL -- TO HEAR AMERICA TALKING

CHICAGO — 1966 — Rumpled and shopworn, the interviewer turned on his tape recorder. His subject was “just a housewife,” but she talked and talked about her life.

When the interview was done, the kids asked for a playback. They laughed, howled, but the woman put her hand to her mouth. “I never knew I felt that way,” she said.

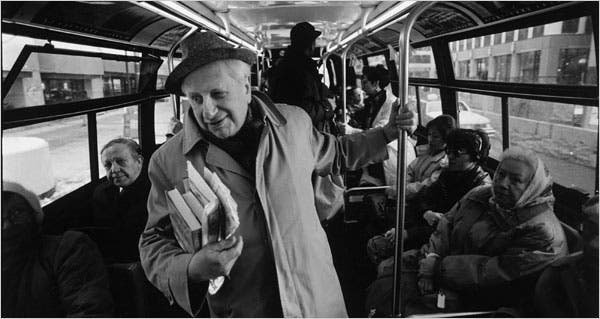

There are artists with a brush and artists with a pen, but Louis “Studs” Terkel was an artist with an ear, and a heart as big as Chicago. For almost a half-century, his radio show featured interviews with the newsworthy, but in his spare time Studs lent his ear to “the etceteras of history.”

Shopkeepers. Barbers. Secretaries. Rich and poor, black and white, despairing or hopeful, Studs Terkel got them all to talk.

“For Studs,” a friend said, “there was not a voice that should not be heard, a story that could not be told." Now online, The Studs Terkel Radio Archive is “the collective memory of our time,” but in his books, you hear America let down its guard and just talk. Talk about jobs, memories of war and Depression, dreams and deepening concerns. So who was this artist who got people talking?

Born in 1912 — “I came up the year the Titanic went down" — Terkel was a walking archive of the 20th century. In 1920, his Russian immigrant family left New York’s Lower East Side to run a rooming house in Chicago. Right in his kitchen the boy heard America, but just a few blocks away he got an alt-education in Bughouse Square.

“I delighted in it,” Terkel said of the home to speakeasies and soapbox orators. “Perhaps none of it made any sense, save one kind: sense of life."

Terkel earned a law degree but chose a different path. Joining a theater group, he later migrated to the newest medium — television.

“Studs’ Place” saw Terkel running a diner and talking with whoever dropped by. The show lasted only a year but got Terkel into the public eye. In 1952, he blended jazz and interviews into a weekly radio show on WFMT-FM. Within weeks, he was on daily. He stayed there until 1997.

Archived interviews reveal how Studs got people to talk. His voice, his demeanor are warm and inviting. A young Marlon Brando, fascinated by Terkel, asked for a second hour. The famous — Lily Tomlin, Marc Chagall, Muhammad Ali — found him anything but fawning. The infamous — Stokely Carmichael, Frank Zappa, Greenpeace activists — found him wide open to their ideas.

Interviews came and went, but one led further. In 1965, a British actress recommended Studs to a publisher. The publisher suggested he take to the streets to talk about the growing American divide. Terkel was soon “on the prowl for a cross–section of urban thought. . . some balance in the wildlife of the city.”

In 1967, Division Street: America sampled 70 lives. A cop, a gang leader, a socialite, an Appalachian migrant mother. . . Previous oral histories had focused on historical events, major figures, but Terkel just let people talk, then wove their lives into human fabric.

Next came Hard Times, an amazing oral history of the Depression. Then in 1974 — Working.

Phil Stallings, spot welder: "I stand in the same spot, about two- or three-feet area, all night. The only time a person stops is when the line stops. We do about thirty-two jobs per car, per unit. Forty-eight units an hour, eight hours a day. Thirty-two times forty-eight times eight. Figure it out. That's how many times I push the button."

Delores Dante, waitress: “People imagine a waitress couldn’t possibly think or have any kind of aspiration other than to serve food. When somebody says to me, ‘You’re great, how come you’re just a waitress?’ Just a waitress. I’d say, ‘Why, don’t you think you deserve to be served by me?’”

In a nation overworked and underpaid, Working struck a nerve. A huge best-seller, its stories later graced a PBS special, a Broadway musical, a James Taylor song, and a graphic novel.

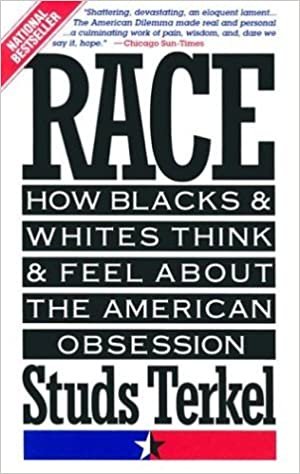

Terkel moved on to hear “the etceteras” talk about American Dreams: Lost and Found. About The Good War. About Race: The American Obsession.

Terkel was 73 when The Good War won the Pulitzer. Retirement beckoned, yet he still loved what he did and people loved his sincerity, his wit, his curiosity. He never drove a car, never even had a driver’s license. Most days, he wore a red checkered shirt, a loosened red tie, gray pants, blue blazer. “I have to take him out to the store to buy clothes,” said Ida, his wife of 60 years. “Otherwise, he would be dressed in rags."

On into this century, Studs Terkel kept talking and listening. In 2004, at 92, he survived open heart surgery, calling himself “a medical miracle.” Terkel died in 2008 at 96. Defying the daily cigars, the non-stop work, his secret to longevity was simple — he liked people.

Studs Terkel, author Tom Wolfe said, was “one of those rare thinkers who is actually willing to go out and talk to the incredible people of this country.”

Terkel asked that his ashes be mixed with Ida’s and scattered in Bughouse Square. "It's against the law,” he said. “Let 'em sue us."