TRACY K. SMITH -- DOWN ROADS NOT TAKEN

Back in fifth grade, Tracy K. Smith read a simple poem. It began:

I'm nobody, Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

The words, written by a reclusive woman from Massachusetts, spoke to a shy girl in California. Smith remembered "feeling like I was in collusion with someone that knew more about me than I knew about myself." Smith memorized the poem, then wrote one. "Keep writing," her teacher said.

September 13, 2017 was another damn newsday. Hurricane sweeping across Florida. Apple unveils a new phone. And the president, the president. . . .. But across town in Washington, DC, a soft-spoken woman signed a guestbook at the Library of Congress. Other signatures included Robert Frost, Elizabeth Bishop, and Billy Collins. At the bottom was the signature of the newest Poet Laureate of the United States, Tracy K. Smith.

Most poet laureates promote their craft -- in schools, in public spaces, online. And in the country Walt Whitman called "essentially the greatest poem," most poet laureates have come and gone. During her two-year tenure, Tracy K. Smith pursued a different path.

In rural South Carolina, young girls lined up to hear the first poet who thought they might care about them. On a pueblo in New Mexico, the scene rhymed. Likewise, on a desert air force base, a Detroit school, a bookstore in Beijing. During a 22-state tour, America's poet laureate went from the streets of Atlanta to the wilds of Wyoming, and beyond.

In each far flung place, Smith offered poetry as a balm for troubled times. "This is a strange period,” said, “where, nationally, we’re being reminded or convinced of the great divisions that separate coastal and urban communities from the central and rural communities. I’ve always distrusted that. I think there are lots of places where we have something very clear, compelling and welcome to say to one another. I’m interested in the way our voices sound when we dip below the decibel level of politics."

Between childhood and her current mission, Smith, 49, took the poet's proverbial "road not taken." The youngest of five children, known to all as "Kitten," she recalls a family that proved "there was such a thing as a happy black family." But beyond Emily Dickinson, she did not read much poetry back in Fairfield, California. Poetry, she thought, was the work of dead writers. Only at Harvard did she meet a Dark Room Collective (above) that celebrated black poets from Langston Hughes to Natasha Trethaway, a future poet laureate.

An MFA at Columbia immersed Smith in Brooklyn bohemia and in her own thoughts. In each state of mind, she learned that a poem might be about anything.

Smith has written about Levon Helm, drummer for "The Band," about Westerns, and about David Bowie, whose picture hangs in her house in Princeton, where she chairs the creative writing department.

He leaves no tracks. Slips past, quick as a cat. That’s Bowie

For you: the Pope of Pop, coy as Christ. Like a play

Within a play, he’s trademarked twice. The hours

Plink past like water from a window A/C. We sweat it out,

Teach ourselves to wait. Silently, lazily, collapse happens.

But not for Bowie. He cocks his head, grins that wicked grin.

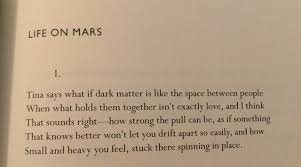

Smith’s Pulitzer winning collection, Life on Mars, features poems about her father, an engineer for the Hubble Space Telescope.

The first few pictures came back blurred, and I felt ashamed

For all the cheerful engineers, my father and his tribe. The second time,

The optics jibed. We saw to the edge of all there is—

So brutal and alive it seemed to comprehend us back.

Smith also, inevitably, writes about race. "Pain was part of my birthright, the very particular pain that was tied up in blood, in race, in laws and war." She still remembers the kid in high school who asked her whether African-American literature was "as good as our literature." African-American literature, she replied, "is our literature."

Yet Smith is wary of using race as a club, either the kind you join or the kind you wield. Though race, she says, “is an unresolved region of our life as a nation, we’re so much more important to one another as individuals — with experiences and questions and histories — than we are as social categories. It’s important to think about those sources that are saying, wait, you have a mother, and this is your relationship with her, this is what you wish could be different. . . I have a mother too, and she looks nothing like yours, but we can have something to say to each other. Those are the kind of conversations that art fosters. I think they’re incredibly necessary right now. Always."

When Tracy K. Smith's term as poet laureate expired in 2018 she was "Nobody" no longer. She was quickly nominated and appointed to a second term. Just as in fifth grade, poetry made her feel "privy to magic," a magic she continues to share with America.