FIGHTIN' WORDS -- WEBSTER AND THE DICTIONARY WARS

NEW ENGLAND, 1790 — Listen up students. Here’s an article about the American language. Read it carefully. This will be on the test.

“This freedom of language wil be excused by the frends of the revolution and of good guvernment. . . On such occasions a riter wil naturally giv himself up to hiz feelings, and hiz manner of riting wil flow from hiz manner of thinking.”

Now, would you buy a new dictionary from this man?

* * *

Today we search for words in dot-coms. Dictionary.com. Thesaurus.com. Wordnik.com But when America first broke free of British rule, the American language was up for grabs. Whoever could pack the most words between two covers, with the sharpest definitions, the easiest pronunciation, the most common spelling, would win “The Dictionary Wars.”

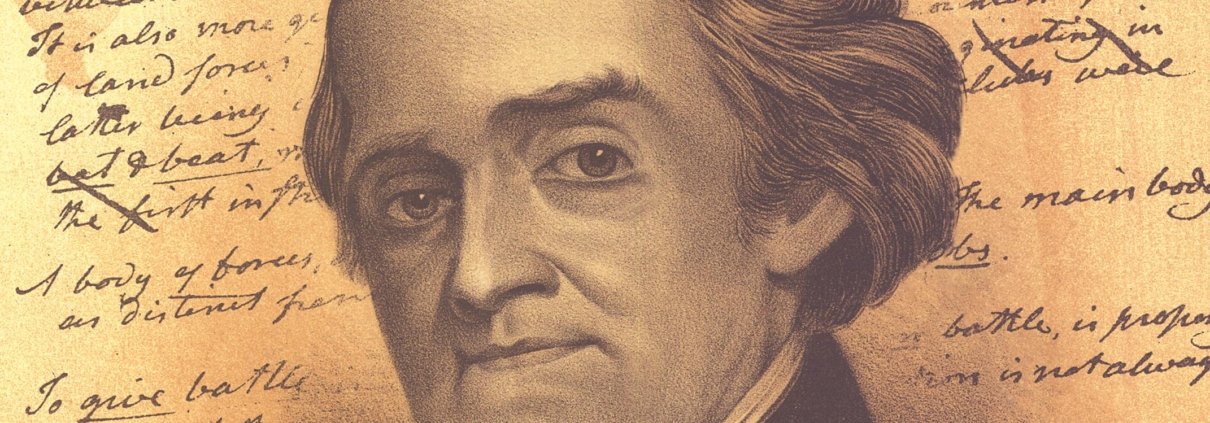

The two generals had similar backgrounds. Bookish boys, each had grown up on a New England farm, reading more than parents thought good for them. But while Joseph Worcester was loyal to the King’s English, Noah Webster cherished all things, all words, American.

English dictionaries had abounded since Samuel Johnson’s first in 1756 but Johnson loathed “the American dialect,” which he defined as “a tract of corruption.” Noah Webster disagreed.

“As an independent nation,” Webster wrote in 1789, “our honor requires us to have a system of our own, in language, as well as government. . . Now is the time, and this is the country. Let us then seize the present moment and establish a national language as well as a national government.”

Pompous and arrogant, Webster had few friends, only converts. But his first book, The American Speller, made him a fortune. The book’s quixotic campaign against silent letters fell flat. America wasn’t ready for “riter,” “giv,” and “frends.” But Webster’s “blue-backed speller” sold millions, allowing him to spend two decades compiling his landmark Dictionary of the American Language.

With 70,000 words, including 1,200 ignored by those snooty Brits, Webster’s work had the weight of authority. But the massive volume sold for the equivalent of $500, and it did not sell well. Could someone do better?

In 1830, two year after Webster’s opening salvo, Joseph Worcester fired back. Worcester’s dictionary had fewer words than Webster’s, yet it cost less and did not hint of a hernia to those who hefted it.

Outraged, Webster wrote to Worcester, asking whether he had stolen definitions. “No, not many,” Worcester replied. Webster then charged plagiarism and took the charge to America’s newest battlegrounds.

The Dictionary Wars raged in a country awash in print. During the 1830s, newspaper circulation doubled. By mid-century, America had some 2,000 newspapers, up to a dozen dailies in each major city. Journalists, with their bottomless appetite for conflict, eagerly stoked this “battle of the books.”

Joseph Worcester, one paper charged, had “pilfered the products of the mind, as readily as the common thief." But other papers called Webster “a quack and an ignoramus.” Even among scholars, one noted, “There are not ten in a hundred who accept Webster’s Dictionary as a standard of language.”

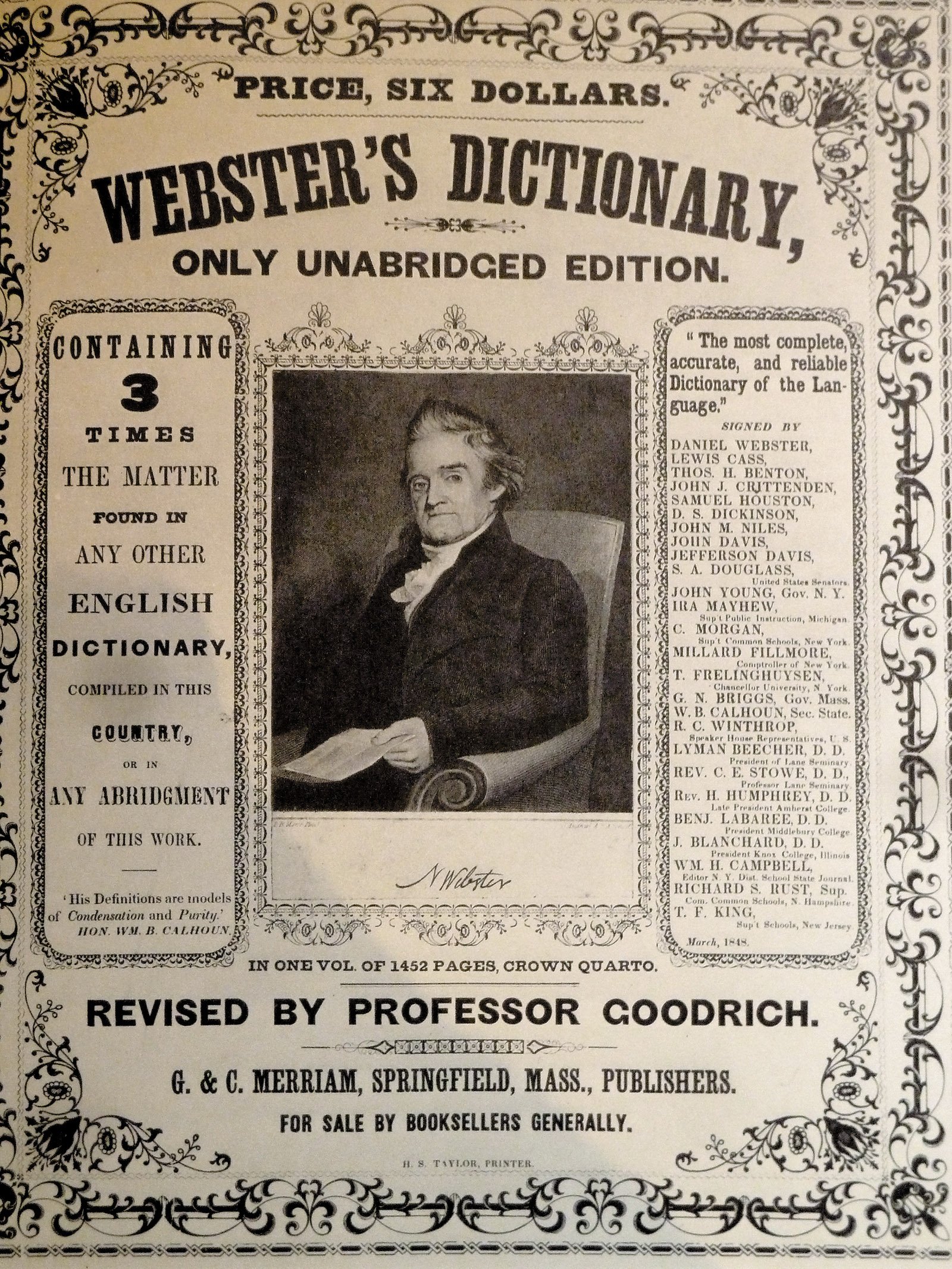

When Webster died in 1843, the wars amped up under that other name on the title — Merriam. Before meeting Webster, George and Charles Merriam published law books and Bibles, but after finagling the posthumous rights to Webster’s dictionary, the brothers began firing at Worcester with both barrels. When Worcester’s latest dictionary came out in 1846, the Merriams paid Webster’s son to find stolen definitions. He found none, but charges of plagiarism continued, along with a skirmish over reputations.

Noah Webster, the Merriams said, was “Schoolmaster of Our Republic.” Joseph Worcester was a “gross literary fraud.” Words flew like bullets. “Corruption.” “Perversion.” “Literary pirate.”

More than money was at stake. Worcester’s dictionary harkened back to the British spellings he thought "more harmonious and agreeable." But Webster’s was new and fresh, embracing American coinages from advocate, which Ben Franklin doubted as a word, to zea, a kind of native corn.

Like his early speller, Webster’s dictionary Americanized hundreds of British words. “Plow” and “jail,” not the clumsy “plough” and the, god forbid, “gaol.” Theater and center, not (ahem!) theatre and centre. “No intelligent man,” the Merriams charged, no “teacher of youth” would ever use such Worcester coinages as squeezable or strengthfulness, let alone jiggumbob, pish-pash, or somberize.

Throughout the 1850s, in pamphlets, articles, and dictionary after dictionary, the wars continued. Then in 1864, as Americans bloodied battlefields far from metaphorical, Merriam-Webster emerged triumphant.

Boasting 114,000 words, the American Dictionary of the English Language used shorter definitions, clearer pronunciation guides. Professors, pundits, and writers agreed. Part Webster, part Worcester, this Royal Quarto Edition ended the Dictionary Wars, making Webster a household name, leaving Worcester merely the name of a Massachusetts city.

“A dictionary,” Mark Twain wrote, “is the most wonderful of all books, it knows so much.” Writing of Webster’s new standard, Twain added, “To me this one is the most awe-inspiring of all dictionaries because it exhausts knowledge, apparently. It has gone around like a sun, and spied out everything and lit it up.”

Now students, for the test. Apply your spell checker to that second paragraph.