THE CHRYSLER BUILDING AND THE RACE TO THE SKY

MANHATTAN — APRIL 1913 — As dusk settles, thousands gather in City Hall Park. All are looking up, up, at the shadow of a spire stretching to the sky. The new Woolworth Building climbs to a crown, a bronze pyramid that reaches 792 feet — the tallest building on earth. And when President Wilson presses a button in the White House, 80,000 lights blaze from top to bottom. Amazing! Colossal! Who will ever build higher?

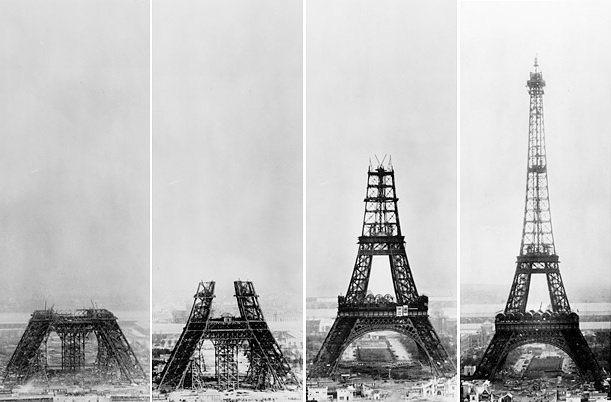

Ever since the Tower of Babel, height has inspired awe. And from the Pyramids to cathedral spires, from the Washington Monument to the Eiffel Tower, each soaring structure issued a dare — top this! But building Manhattan’s tallest took a trick up an architect’s sleeve.

William Van Alen was a shy, awkward man, more at home behind a drawing table than in business. But his work, one client said, was “so darned clever that I don’t know whether to admire it or hate it.” Van Alen’s partner, Craig Severance, took care of the firm’s finances. On into the 1920s, Severance and Van Alen put up several tall buildings, but when the men clashed, split, went to court, the stage was set for the race to the sky.

After the split, Van Alen struggled, designing restaurants and stores. Then in 1927, he was summoned to the office of Walter P. Chrysler.

Chrysler was a Kansas farm boy whose life soared like a skyscraper. Rising from factory mechanic to head of General Motors, then forming his own company, Chrysler, wrote TIME in making him its Man of the Year, was “fabulous, prodigious, a torpedo-headed dynamo from Detroit.” Today, such a tycoon might build a McMansion or go into space but in the 1920s, other outlets for ego beckoned.

“I came to the conclusion that what my boys ought to have was something to be responsible for,” Chrysler said. “They wanted to work, and so the idea of putting up a building was born.”

Buying a large lot on Lexington and 42nd, Chrysler inherited the architect already making plans for the site. But Chrysler told Van Alen to scrap his plans. “I want a taller building of a finer type of construction and it’s your job to give the best that’s in you.” Money was no object. No fee was set, no contract signed. Everything was left to dreams and blueprints.

Meanwhile down on Wall Street, Craig Severance read of his rival’s new building, planned for a record 809 feet. That afternoon, horseback riding in Central Park, Severance told his daughter, “I’m going to build the tallest skyscraper in the world.” 850 feet would do it, and within days, 40 Wall Street was being designed.

Back in midtown, Walter Chrysler heard of the challenge and summoned Van Alen. Handing his architect a blank check, he said, “Make this building taller than the Eiffel Tower.” But both men saw the handwriting on the wall. If they announced 860 feet, Severance would go for 900. When they announced 900. . . So they agreed on a secret plan, and Van Alen went back to the drawing board.

Construction on the Chrysler Building was underway. Girder by girder, the building climbed above Grand Central Station. 40 Wall Street only broke ground that June. It would not be finished before Chrysler, but as if Craig Severance willed it, it would be taller.

As construction continued, other architects chomped at the bit. One promised a building reaching 1,500 feet, another dreamt of 100 stories. It was 1929, the stock market was soaring, and as President Coolidge had said, “the business of America is business.”

By October, the Chrysler Building topped off at 809 feet. Though scaffolding still hid Van Alen’s fabulous chrome-steel Art Deco design, the building was done. Manhattan’s tallest! But 40 Wall Street had upgraded plans to top 900 feet. Then Van Alen put his secret to work.

On October 15, a derrick began hoisting tall steel pyramids up the brick edifice. Dozens were lifted and stored inside the Chrysler building’s cavernous crown. Soon they were assembled, one atop the other. On October 23, from out of the rounded pinnacle high above Manhattan, the spire emerged “like a butterfly from a cocoon,” Van Alen remembered.

Foot by foot, the 27-ton needle rose. A strong wind or snapped cable would send the spire crashing to the street. “Balancing an elephant by his trunk on top of the building would have been an easier proposition,” Neal Bascomb wrote in Higher. When the full spire cleared the crown, riveters quickly locked it place. And then the coolest thing happened — nothing.

“We’ll lift the thing up and we won’t tell ‘em anything about it,” Van Alen said. “And when it’s up we’ll just be higher, that’s all.”

The next morning, the stock market began to teeter and all attention was on Wall Street. Not until mid-November did newspapers notice Van Alen’s trick. With its silver arches unveiled, the Chrysler Building was “a shining, shimmering thing, like the work of some silversmith.” And Van Alen’s masterpiece stretched to 1,046 feet, the first building to top 1,000 feet, the tallest in the world.

William Van Alen never designed another major building. And in 1931, the Empire State Building was finished, standing taller than the rest for the next 40 years. But with Van Alen’s dreamlike design, the Chrysler Building remains, as one skyscraper history noted, “the belle of the New York skyline.”