HOW HERBERT HOOVER SAVED MILLIONS

“The war against hunger is truly mankind’s war of liberation.”

EUROPE 1914 — The guns of August exploded into war. By winter famine was looming.

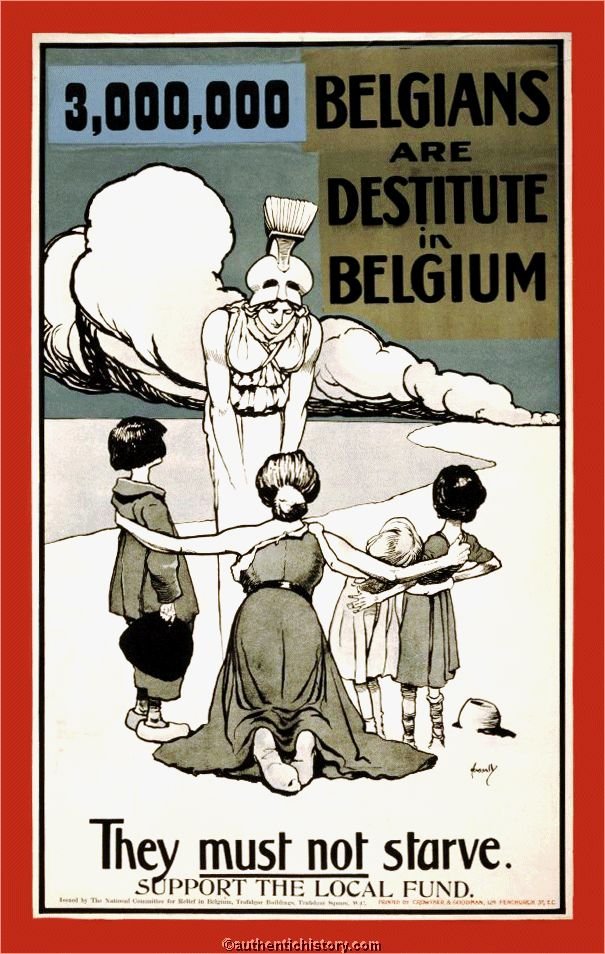

German troops had swept across Belgium, pillaging, burning. The small nation, Europe’s most industrialized, produced only a quarter of its food. With imports cut off by blockade, seven million people faced starvation.

That autumn, Herbert Hoover was a wealthy mining engineer living in London and wondering, at age 40, what to do with the rest of his life. Then he got word from the American embassy about Belgium.

Raised a Quaker, orphaned at age ten, Hoover had risen to become the model of efficiency in an age that prized production. Running mines in Australia and China, he soon became the “doctor of sick mines” with clients and offices around the world. But now he faced the razor’s edge of hunger.

“It was an unparalleled feat that had never been attempted and was thought to be impossible,” writes historian Jeffrey Miller in Yanks Behind the Lines. “Private citizens of a neutral country feeding an entire nation caught in the middle of a world war.”

By mid-October, as trench warfare dug in, Hoover had a plan. Germans would allow no enemy combatants to enter Belgium, but America was still neutral. So Hoover began recruiting fellow “Yanks.”

On December 4, 1914, Hoover addressed the first delegates of his Commission to Relieve Belgium. Many were Rhodes Scholars studying at Oxford. Others were journalists, businessmen, ordinary Americans responding to crisis. “When this war is over,” Hoover told his recruits, “the thing that will stand out will not be the number of dead and wounded, but the record of those efforts which went to save life.”

The first ship had already docked in Rotterdam, bringing 1,000 tons of wheat, rice, beans, and peas. Other ships would follow. Now it was up to CRB delegates to go behind the lines to help a Belgian relief group distribute food through 2,600 local co-ops. Loaded on barges and sent down Belgium’s elaborate network of canals, the food soon began arriving.

At 11 a.m. each morning, lines formed and tickets were redeemed. Each family received a half-liter of soup and a loaf of bread for each hungry mouth. Roaming Belgium, CRB delegates marveled at the calm, the endurance of the occupied nation. “There is no eternal standing in line,” one said. “Twelve hundred are dealt with in an hour at any table of any one station; there is no crowding or cursing or need of police.”

But as the Great War dragged on, trouble loomed. The British hoped Belgian food riots would distract the Germans. Hoover had to convince the Brits to lift their blockade for relief ships. The French were hungry, too, until Northern France was added to relief efforts.

Germans suspected spies and harassed or jailed CRB delegates. Though each relief ship was marked by banners, German U-boats sank thirty-eight vessels. Hoover, working 14-hour days, crossing the English Channel forty times during the war, master-minded the operation.

To secure loans and food donations, Hoover negotiated with governments from England, France, Spain, the Netherlands, and the U.S. And his CRB appealed to the world’s compassion, collecting $52 million (more than a billion dollars today) in private donations. “Belgium is like a person slowly bleeding to death,” one American magazine wrote, “and only the care of the whole world can save her.”

And food kept coming. Forty ships each month. A million tons in the war’s first year, more the next. By the time Americans entered the war, forcing Hoover’s delegates to leave Belgium, the CRB and its collaborators had distributed five million tons of food.

In the spring of 1917, Hoover went to Washington to become America’s “food czar.” His US Food Administration set up a campaign of Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays that kept Americans fed and kept surplus food flowing to Northern Europe. After the war, he led the American Relief Association, a massive program to feed war-torn Europe, including Germans and Russians. Accused of aiding Bolshevism, he shot back, “Twenty million people are starving. Whatever their politics, they shall be fed!"

“The evil men do lives after them,” Shakespeare wrote. “The good is often interred with their bones.” Today Herbert Hoover is best known for his conflicted response to the Great Depression which deepened as he refused the massive federal effort later engineered by FDR.

But ask a Belgian. Ask a Frenchman, a German, a Russian. Stories of hunger and relief, passed down through generations, tell of nations still grateful to Herbert Hoover, “The Great Humanitarian.”

Speaking in Belgium in 2006, Hoover biographer George Nash summed up the effort. Thanks to Hoover “between 1914 and 1923, more than 80 million people in more than 20 nations received food allotments.” As the “Napoleon of Mercy,” Nash said, “Hoover was responsible for saving more lives than any other person in history.”