VERA RUBIN, DOYENNE OF DARK MATTER

WASHINGTON, D.C. — 1938 — In the glittering darkness, a girl looks out her bedroom window. She sees the stars wheeling in silence. She learns celestial names. Orion. Cassiopeia. The Pleiades. But what are they? What makes them shine? “Even then I was more interested in the question than in the answer,” Vera Rubin remembered. “I decided at an early age that we inhabit a very curious world.”

The universe hasn’t changed much since the young girl wondered about it. But our understanding of the cosmos has expanded more in the last 50 years than in all the previous millennia. Fantastic space telescopes. Planetary probes. Quasars, gravity waves, string theory. . . The list goes on. And one item on that list is forever tied to that girl who looked out her window. Dark matter.

“Her work helped usher in a Copernican-scale change in cosmic consciousness,” the New York Times wrote of Vera Rubin. “Namely the realization that what astronomers always saw and thought was the universe is just the visible tip of a lumbering iceberg of mystery.”

Rubin’s path to the cutting edge of astronomy was strewn with familiar obstacles. Her father, an engineer, helped her build her first telescope. She studied at Vassar, choosing it because Maria Mitchell (above) had made the college a magnet for female astronomers. But then came marriage, children, and the dark energy of men as hidebound as a flat earth society.

An aspiring female astronomer, Rubin wrote in 1986, “will often enter a department where she will be the only woman student. There will be no women on the faculty. . . One faculty member may proclaim openly that he doesn’t want a woman to work with him. Her work will be scrutinized with a care that most of her male classmates will be lucky enough to escape. She will stand out in everything that she does.”

Rubin stood out for reasons beyond gender. Whipsmart and driven, she earned her Ph.D. while raising four children, then began teaching. When her early work was rejected, Rubin sought a topic “nobody would bother me about.” She chose a puzzle nearly a century old.

Since the 1880s, astronomers had studied galaxies and how they spin. Just as the outer planets in our solar system, farther from the sun’s gravity, revolve more slowly than inner orbs, stars far from a galaxy’s hub should plod along. Their speed should be tied to a galaxy’s mass, as measured by brightness.

But something wasn’t adding up.

Far flung stars were moving faster than Newton’s laws predicted. There just had to be more mass — and gravity — at each galaxy’s center to keep them from flying away. But that mass could not be seen. Was there some mysterious matter that refused to shine? “Nobody ever told us all matter radiated light,” Rubin said. “We just assumed it did.”

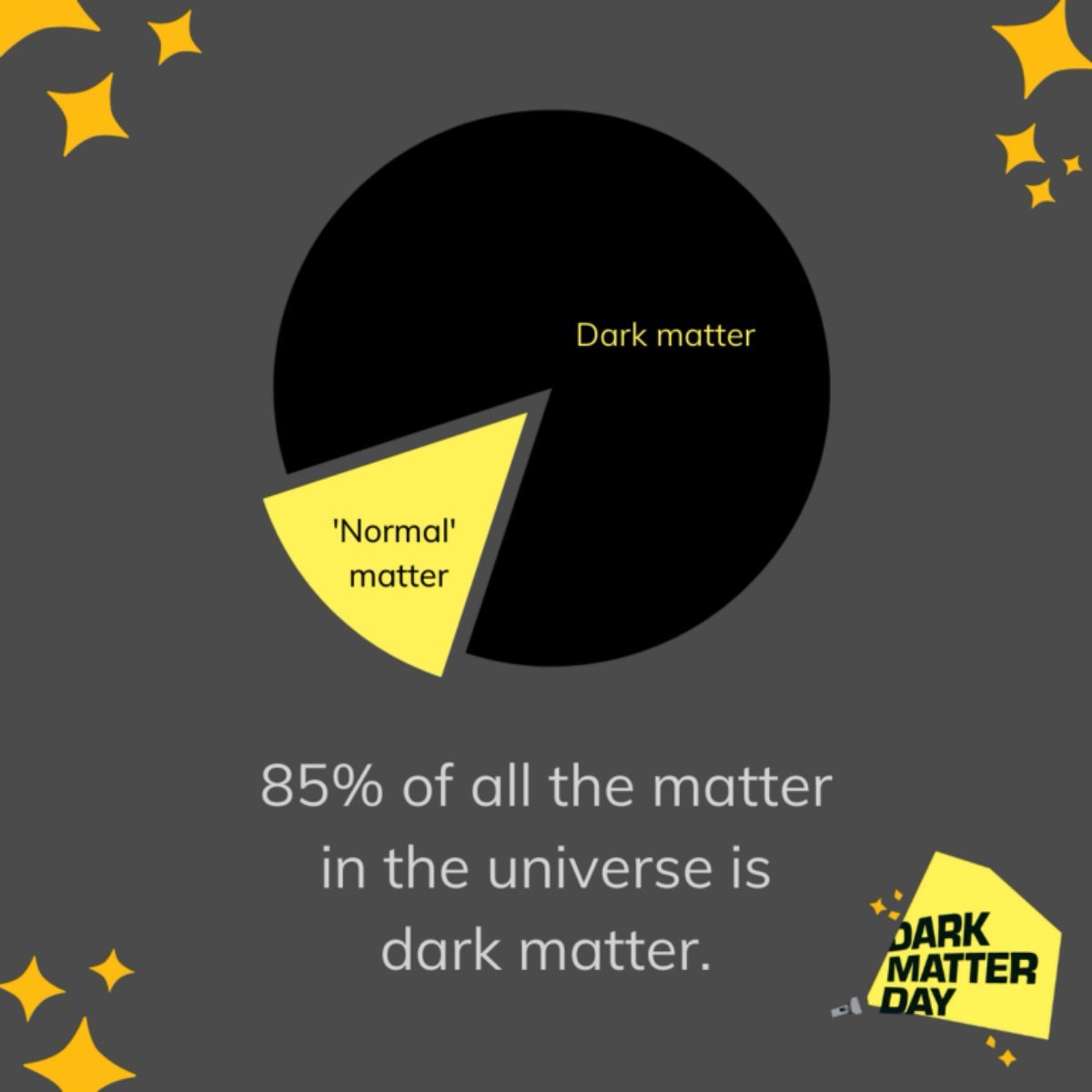

In the late 1960s, Rubin began studying the Andromeda Galaxy. Using the latest instruments, she crunched the numbers across the universe. She was astonished. Dark matter and dark energy, whatever they might be, made up well more than half the mass of the cosmos. When Rubin’s team announced their findings in 1975, astronomers scoffed. Sexism may have played a role. After all, the Palomar Observatory where Rubin used the world’s largest telescope did not even have a women's restroom — until Rubin taped a paper skirt on the men’s restroom door.

Undaunted, Rubin’s imagination soared through the universe as she studied some 200 galaxies. Slowly, gradually, the mass of men at the center of astronomy weakened. The girl who had looked out her window was right. No one knew what dark matter was — we still don’t. But as one astronomer noted, “Vera’s work, mostly in the early ’80s, clinched the case for dark matter for most astronomers.”

Like Maria Mitchell, Rubin became a role model. Letters from young girls poured in. “You are a lucky young lady,” Rubin wrote to a fifth grader, “for you will someday know what kind of material constitutes the dark matter. But if you are especially lucky, you may puzzle over some new questions we cannot now even imagine asking.”

Vera Rubin died in 2015. By then she had won most major honors in astronomy — except the Nobel in physics that many thought she deserved. “Alfred Nobel’s will describes the physics prize as recognizing ‘the most important discovery’ within the field of physics,” a colleague said. “If dark matter doesn’t fit that description, I don’t know what does.” But Rubin cared less for awards than for the joy of asking questions in a very curious world.

“I’m sorry I know so little,” she often said. “I’m sorry we all know so little. But that’s the fun, isn’t it?”