JACOB LAWRENCE -- BLACK AND WHITE IN COLOR

HARLEM, 1930 — The kid named Jake left the Y where he’d been shooting pool. Another walk home through the mean and magical streets. On one corner, musicians belted out jazz. On others, speakers preached about the evils of capitalism, the call of Africa, justice for the Scottsboro Boys. The kid walked past but stopped at the open door of a small meeting.

Inside, a tall, skinny man spoke. Black people, he said, would never amount to anything “until they know their own history and take pride in it.” Jake edged inside. Know your history, the tall, skinny man preached.

When he was finished, Jake approached. I’m an artist, he said. Or want to be. The man asked — had he seen the sculptures from West Africa? At this museum called the Met? Come.

Jacob Lawrence never set foot in a gallery until he was 18. Within five years, he was the talk of New York’s art world. We are tempted to worship “natural talent,” but Lawrence put in the hours, the 10,000 hours they say are needed for mastery. He logged those hours in both studio and the street.

Growing up in Atlantic City, Lawrence heard stories of the South. How his parents had joined “the great migration.” How they, and a million others fled Jim Crow to find “the warmth of other suns.” But his parents divorced when Jake was seven and he landed in foster care. He lived in Philadelphia, then reunited with his mother at age 13. In Harlem.

They speak now of a Harlem Renaissance. Poets Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. Novelists Jean Toomer and Zora Neale Hurston. Black souls on parade, on paper, on canvas. Jacob Lawrence was late to the Renaissance but he soaked it up. And when his mother enrolled him in an after-school art class, his drawings spoke volumes.

Here were colors few had paired. Sky blues with blood reds. Bold blocks of green and yellow. The teacher recommended more classes, but Jake was just a kid. He wanted to shoot pool and hang on street corners. So he listened to art teachers, but mostly he listened to Harlem. He dropped out of school, worked as a delivery boy, walked the streets. And on the advice of the tall, skinny man, he read black history.

He read of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. He recalled stories his parents told about lynching. None of this had been taught in school. None. “Having no Negro history makes the Negro people feel inferior to the rest of the world,” Lawrence said. And he continued to paint Harlem. Men playing dominoes. Women ironing. The library. The front porch. The barber shop.

At 18, Lawrence had his first one-man show at the Harlem Y. “The place of Jacob Lawrence among younger painters is unique,’ artist Charles Allston said. “Having thus far miraculously escaped the imprint of academic ideas and current vogues in art, to which young artists are most susceptible, he has followed a course of development dictated entirely by his own inner motivations.” With Allston’s help, Lawrence painted for the WPA, then began a series of series.

No single painting could capture Frederick Douglass, so Lawrence painted thirty-two. No lone masterwork could embody Harriet Tubman. Lawrence did thirty-one. And when he got a Guggenheim to paint “The Migration of the Negro,” Lawrence moved into a fleatrap studio with no electricity or running water and laid out sixty small Masonite panels.

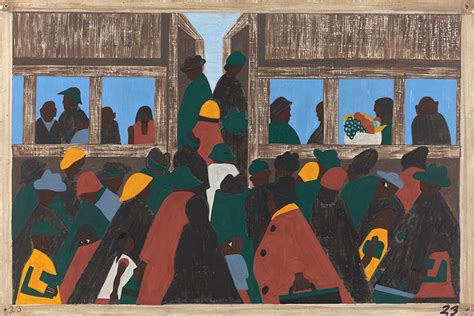

He began with dark colors, moving from one panel to another. Working on all sixty at once, he added lighter colors, and still lighter. He painted crowds clamoring into northbound trains. He painted blacks huddled together watching birds fly. Here was the surge and energy of a people. Here were tears and triumph.

Asked if his family had any artists, Lawrence said “no,” then thought better. ”It’s only in retrospect that I realized I was surrounded by art. You’d walk Seventh Avenue and look in the windows and you’d see all these colors in the depths of the Depression. All these colors.”

In the summer of 1941, Lawrence was honeymooning in New Orleans when he got a letter from New York’s prestigious Downtown Gallery. Would he show his Migration Series? “American Negro Art: 19th and 20th Centuries,” included Henry O. Tanner, Romare Bearden, and others. But it was Lawrence’s Migration Series that was featured in magazines, talked about, sold.

There followed, in no particular order, success, struggle, teaching, depression, revival. But painting, always painting. With his work now in 200 museums, the kid named Jake, who died in 2000, became one America’s most beloved artists. And the word “black” is not in that sentence.