"THE FAMILY OF MAN" -- STILL SHOWING US US

THE COLD WAR — 1950s — As the shadow of a mushroom cloud loomed over the world, millions sank in despair. H-bomb tests spread terror. First graders crouched under desks, ducking and covering. Were we no better than this?

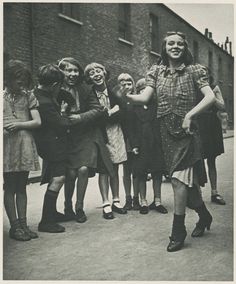

On January 24, 1955, a photo exhibit opened at Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art. The photos showed ordinary people around the world — working, playing, dreaming. Curator Edward Steichen was pleased. The people, he said, “looked at the pictures, and the people in the pictures looked back at them. They recognized each other.”

Today, The Family of Man is a coffee table book. You may have leafed through it, pausing at a photo or two. But during the darkest days of the Cold War, Edward Steichen’s vision toured the world. In Japan, a million people saw The Family of Man. Still more saw the exhibit in India. Crowds lined up across Europe. In Guatemala, Mayan Indians came out of the hills to bear witness. The Family of Man was seen in Teheran, Johannesburg, Moscow, Kabul. . . This singular collection of photos became our family portrait.

Edward Steichen was an icon of American photography. His career dated to the 1900s when he and Alfred Stieglitz opened 291, the first gallery to treat photography as art. Steichen moved on to photograph fashion, nature, any subject that would reveal “that charlatan, Light.”

But by 1950, Steichen hadn’t had a show in years. At MoMA, his job title was Curator. One of his first exhibits focused on war, “the most forceful indictment of the subject ever put forth by photography,” he thought. But the reactions appalled Steichen. People would praise the photos “and then go out and have some drinks.” As the Cold War deepened, as apocalypse loomed, he wondered. Why not use photography to show “how all people were in all parts of the world?”

For the next four years, Steichen gathered images. He toured Europe, bringing home 300 prints. He spoke to Bay Area photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams. “Some of them thought he was kind of goofy,” Steichen’s assistant recalled, “full of pie-in-the-sky ideas.” But Lange, whose Depression photos captured human despair, understood. She put out a call for photos to “show Man to Man across the world. . . Nothing short of that will do.”

Working sixteen-hour days, Steichen and his assistants scoured the archives of Time, Life, and worldwide photo syndicates. They culled through family snapshots and professional portfolios. From 3 million entries, 10,000 made the cut. Then came the “heart-breaking” work, selecting 500. These were sorted into categories — Birth, Love, War, Family, Death. . . Each photo embodied Steichen’s bedrock belief in the human spirit.

“We have survived everything and we have only survived it on our optimism. ”

To stitch themes together, Steichen turned to an old friend, photographer Dorothy Norman. Norman pored through poetry, scripture, and folklore, then handed Steichen a thousand quotes on index cards. Next came the task of reproduction — printing 500 photos not on some digital printer but in darkrooms, with film, chemicals, and paper all at the whim of that charlatan.

Finally. . .

On the eve of MoMA’s premiere, Steichen was frantic. What if the photos were too disjointed? What about that wall-sized mushroom cloud? Was it too terrifying? What if. . . what if. . .

Steichen’s fears were quickly soothed. Looking at faces as they looked at faces, he knew he had touched a nerve. When word spread, lines stretched around the block. Critics raved. Here was “the universality of human emotions.” Here was “the whole story of mankind.” There were cynics, of course, dismissing such “sentimental humanism,” but the world soon put the cynics in their place.

Over the next eight years, The Family of Man toured 69 countries, drawing nine million people. The coffee table book, still in print, sold millions more.

We could use The Family of Man these days. The anger, the fear, the cynics are still with us. From darkness, it seems, come visions of light. Yet the show’s title came not from the Cold War but from the Civil War.

On the Fourth of July in 1861, Lincoln told Congress that the war posed a question. — could democracy survive? The question, Lincoln said, confronted “the whole family of man.”

During the Depression, Carl Sandburg wove Lincoln’s phrase into a poem — The People, Yes.

The people know the salt of the sea

and the strength of the winds

lashing the corners of the earth.

The people take the earth

as a tomb of rest and a cradle of hope.

Who else speaks for the Family of Man?