THE MASTER OF LIGHT

EARTH — NORTHERN HEMISPHERE — This is the season when we celebrate light. The coming month brings the summer solstice, the longest day of the year, when darkness recedes and light is triumphant.

Light has long been many things to many people. The symbol of hope, revival, life itself. Yet no one ever accused light of being slow. Ancient students of light thought its speed was infinite. Notice how starlight fills your eyes as soon as you open them. During the 1600s, the first measurements taken across the solar system suggested a staggering speed — 144,000 miles per second. Then in 1879, ending centuries of speculation about light’s exact velocity, an American physicist nailed it.

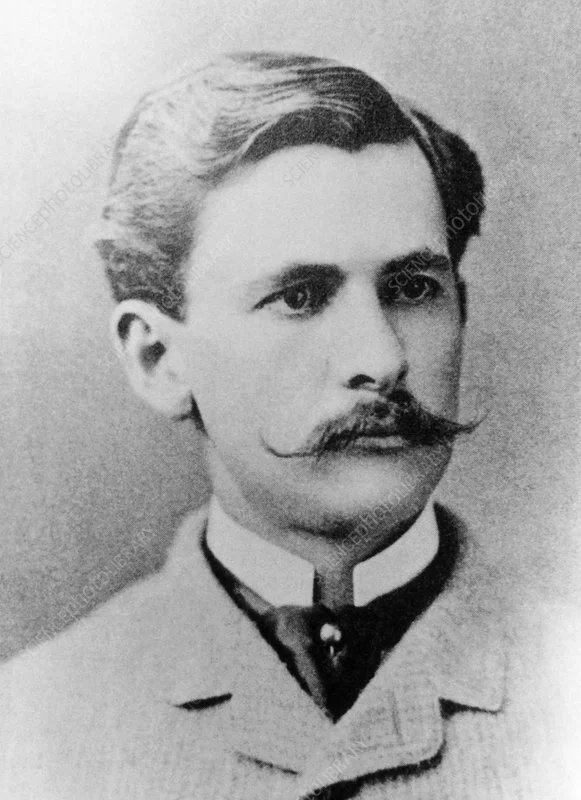

Albert Michelson, born in Poland, came to America as a toddler. Growing up in a Gold Rush camp, he dreamed of going to sea. He hoped to attend the U.S. Naval Academy but could not get an appointment, so he hitchhiked across America, talked his way into the White House, and convinced President Grant to appoint him to Annapolis.

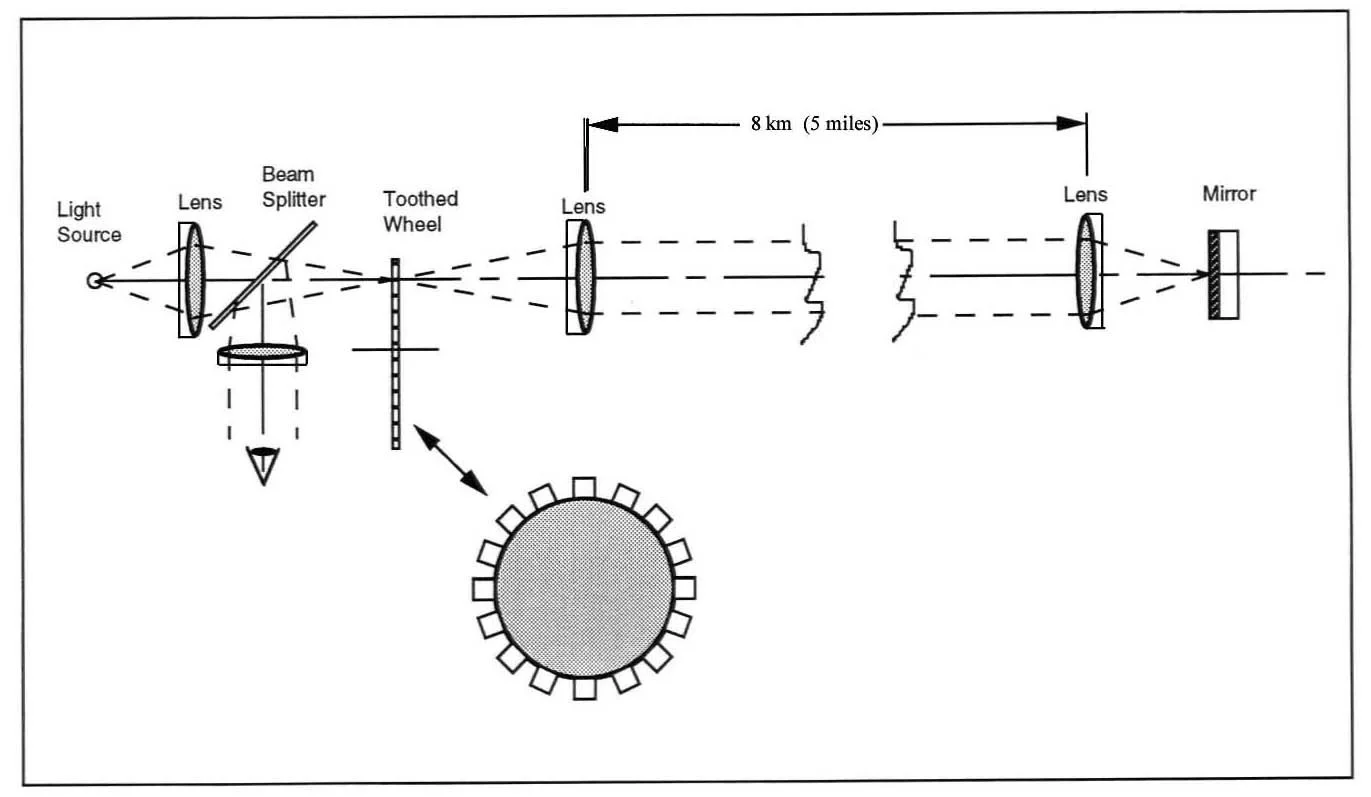

After two years at sea, Ensign Michelson returned to Annapolis to teach physics. There he learned of a nifty new experiment for measuring light’s velocity. Spinning a mirror at 130 revolutions per second, Monsieur Foucault (of pendulum fame) bounced light off the whirling glass and reflected a beam across Paris, the City of Light.

A fixed mirror caught the beam and bounced it back. When it returned, the time of the round-trip was measured in the mirror’s micro-second spin. Dividing time into distance, the beam was clocked at (wait for it) — 186,200 miles per second. Pretty clever, those French, but Albert Michelson was determined to do better.

"It would seem that the scientific world of America is destined to be adorned with a new and brilliant name,” the New York Times wrote in April 1879. “Ensign A.A. Michelson, a graduate of the Annapolis Naval Academy, and not yet 27 years of age, has distinguished himself by studies in the science of optics which promise a method for the discovery of the velocity of light."

Michelson was as exacting as light itself. A buttoned-down man obsessed with precision, he would later work himself into a nervous breakdown. Yet obsession did not blind him to light’s beauty. In lectures, he urged budding physicists to notice “the exquisite gradations of light and shade encountered at every turn.” Michelson was also a skilled watercolorist whose paintings captured the fleeting light of sunsets. And when asked why he studied light, he said, “because it’s so much fun.”

In June 1879, after months of fine-tuning, Michelson was ready. His equipment — a lens, a steam boiler, and two mirrors — cost him ten bucks. Each speed test began an hour after sunrise or before sunset, when light was “sufficiently quiet to get a distinct image.” In a storage shed perched on the seawall of Annapolis’ Severn River, Michelson fired up his boiler. Steam spun the mirror, slowly at first, then so fast it sometimes flew off its mooring. Finally the mirror hit 250 revolutions per second—yes, per second — in 1879.

A memorial on the Annapolis campus traces light’s path in Michelson’s 1879 experiment.

Aiming his lens at the horizon, Michelson caught sunlight and bounced it off the whirling mirror. The beam split the leafy campus. Striking a fixed mirror precisely 1985.09 feet away, the light scorched back to the glass that had since spun juuuusst that much.

Michelson filled his log with data— Date of Test, Temperature, Speed of Mirror — but only one number really mattered. It varied slightly with each test, but on average, Michelson’s measurement —186,319 miles per second—was just 0.0002 percent above the accepted speed only fixed a century later.

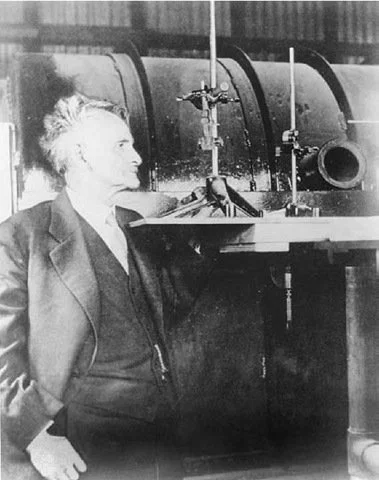

Michelson would spend the rest of his life refining his Annapolis experiment, but not until he had solved the most enduring of light’s enigmas.

Since Aristotle, poets and physicists alike had assumed that light travels through a gel-like “ether.” Sound does not travel through a vacuum so how could light pass through empty space? In 1886, to measure how much the ether slowed light, Michelson bounced beams at perpendicular angles. The beam going against ether’s current should slow it, just as water slows a swimmer crossing a river. But testing and re-testing, Michelson saw no “ether drag.” Ether, he declared, did not exist.

Michelson’s ether experiment set Einstein to thinking about light as a constant, making time relative and disturbing the universe. And in 1907, the test earned Michelson America’s first Nobel Prize in physics.

Albert Michelson spent his final decade at Cal Tech in Pasadena. During the 1920s, when he was in his seventies, he bounced light between Mount Wilson and Mount Baldy. Extending his beam’s round-trip to 22 miles, spinning an 8-sided prism at 30,000+ rpm, he fixed a speed—186,285 miles per second—that would stand until the age of lasers. And that, even in these bright days, is reason to shine a light.